Transit agnosticism: “the idea that when it comes to getting around, everything from bikesharing to the subway will do.”

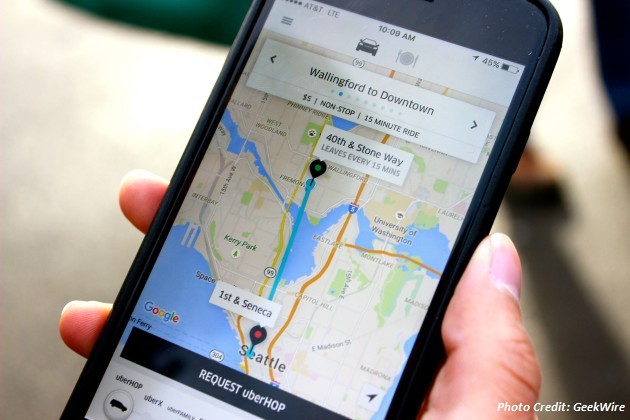

This is the term USA Today used to describe an open, flexible approach to mass transit. It means that mass transit isn’t confined to rail or buses. In 2017, it “can be anything that gets you where you’re going – whether it’s on rails or hailed through an app.”

Randal O'Toole, transportation expert at Cato Institute, makes this distinction as well when he refers to public transit, clarifying that "public in public transit doesn't refer to ownership; it refers to transport that is available to all of the public."

As expected, some government officials and transit boosters are not fond of this progressive redefinition of mass transit, and prefer the older, outdated approach. They see ridesharing services like Uber and Lyft as “first-last” mile tools that should connect people to traditional mass transit.

Much to their chagrin, Uber and Lyft are many people’s preferred travel mode for their entire trip. This trend makes sense. Why would anyone disembark from Uber in the first mile, adding additional legs to their trip, when they could take one vehicle the whole way directly to their destination?

As a result of this shift, Uber and Lyft are no longer transportation choices government officials and transit boosters can support. Ridesharing services are, instead, treated as competitors and opponents that must be pushed out of business. As O'Toole puts it, government then regulates "privately owned transit to save publicly subsidized transit, because for some reason, subsidzed transit deserves to be 'saved' from private competition."

This does not serve people or increase mobility – it serves traditional mass transit, even when it doesn’t work for all commuters. Most disappointing is that this approach reduces transportation choices and hurts people’s freedom to choose the travel mode that best works for them. Unfortunately, this is a growing sentiment in cities throughout the country.

In a recent New York Times article, author Emily Badger asks, “Is Uber helping or hurting mass transit?” She cites results from a UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies survey of 2,000 people, which “suggest that ride-hailing draws people away from public transit.” According to the study, after people in major American cities try ride-hailing, there is a 6% decrease in bus use, and a 3% decrease in light rail use. Ridesharing users felt that transit was “too slow or unreliable.”

The question The New York Times should have asked instead was whether Uber is helping or hurting people. In a world where transit is no longer a means to an end – but an end in itself – this question seems to be ignored. Badger concedes that ridesharing might be more efficient for people individually, but says it hurts the city collectively because it encourages riders to switch from transit to cars, and cars are bad for dense cities.

The author seems to understand that people choose to rideshare because it is faster and more reliable, but worries that having more cars on the road will reduce overall transportation efficiency, and therefore ridesharing should be regulated. This assumes, however, that people are not rational. In practice, people will stop choosing to rideshare if it becomes slow and unreliable. They do not need to be told. They already know what is most efficient, and adjust faster than politicians.

Meanwhile, in Chicago, Mayor Rahm Emanuel has taken this anti-transportation choices ideology one step further. Emanuel is proposing to increase the current 52-cent tax on all Uber and Lyft Rides in the city by 29%. This would bring the current tax to 67 cents per ride in 2018. The tax would increase to 72 cents per ride by 2019. This represents a near 40% increase in the tax rate in two years.

The tax revenue would go to the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA). Emanuel’s administration does not like that Uber and Lyft compete with traditional mass transit, complaining that “the ride-hailing industry has drained $40 million from city and other local government coffers, in part by shifting some commuters away from the CTA.” In other words, commuters are not making the choice he wants them to make, so they should be punished.

The Chicago mayor is proud of the tax and says, “[Chicago] will be the first city to tap into the ride share industry for resources to modernize our transportation system.” If this statement doesn’t demonstrate that irony is dead, then I don’t know what does.

Rather than hamstring transportation choices that compete with traditional mass transit, government should encourage innovation and allow transportation services to compete with one another.

When we encourage monopolies in mass transit, public transit agencies collect more revenue without any incentive to provide better service, and commuters have fewer transportation choices. On the other hand, when we encourage competition among various mass transit options, we preserve the freedom of commuters to choose the best and most cost-effective mode for their needs. This is the better approach.