Late on September 23rd, an over-height truck struck the SR 167 bridge in South King County. Bridge girders were so badly damaged that WSDOT closed two northbound lanes on that heavily traveled highway. The closure is, even two days later, causing traffic back-ups that stretch for five miles and prompting long round-about detours.

This incident is just the latest in a series of recent bridge closures due to accidents and deterioration of aging structures:

- In April, WSDOT closed the SR 165 bridge over the Carbon River due to corrosion and structural concerns. A year earlier, WSDOT had placed a weight restriction on the 103-year-old bridge. The bridge will need to be replaced but no funding has been identified.

- In August, the SR 410 bridge over the White River was abruptly shut down after it sustained damage from an over-height truck. The closure, expected to last more than a month, necessitates long detours for the 20,000 vehicle trips per day that had used the 76-year-old bridge. With luck, the bridge will re-open to traffic in late October or early November.

- In September, WSDOT closed the SR 169 bridge over the Green River after cracking and corrosion was discovered in the 93-year-old structure. The 11,000 vehicle trips per day that had been using the bridge are now being diverted to lengthy detours that can take up to an hour. Repairs are expected to take about two months.

This could be viewed as just a run of bad luck; after all, there are more than 3,000 bridges on the state highway system in Washington, so it shouldn’t come as a surprise if occasionally one needs to be closed due to damage or deterioration. However, a review of the list of state highway bridges isn’t reassuring. It reveals that 230 bridges are currently rated as being in “poor condition” and hundreds more are overdue for maintenance work.

How did this worrisome situation arise? Was anybody at WSDOT paying attention to bridge conditions? WSDOT actually has a very extensive bridge monitoring program, and they have been calling attention to the deteriorating condition of bridges for a dozen years or more. However, identifying needed preservation and maintenance has not resulted in budgets that fund the work. In 2024 Roger Millar, then WSDOT Secretary, described the state highway system as “being on a glide-path to failure”, but during his tenure the agency’s budget requests to the legislature never fully funded preservation and maintenance.

Over the last ten years the state transportation budget has steadily increased, and now totals about $15 billion for the biennium, but the legislature has made reducing greenhouse gas emissions and encouraging transit and non-motorized travel higher priorities than fixing bridges and highways. As a result, the preservation and maintenance backlog is now so large that WSDOT estimates an additional billion dollars per year is needed to get caught up.

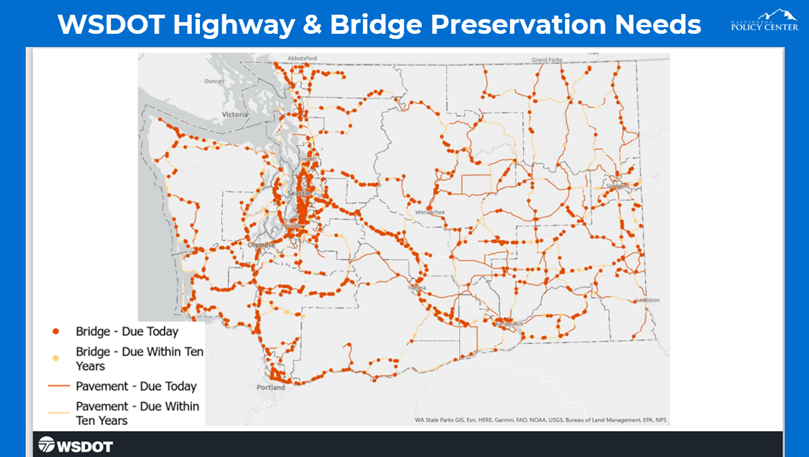

The extent of the problem can be seen on the map below where each orange dot is a state highway bridge that is due (or overdue) for preservation work.

The curious thing about this is that while the condition of the state highway system has been deteriorating, WSDOT has been emphasizing the importance of system resilience. In fact, WSDOT’s Strategic Plan makes resilience one of the agency’s primary goals. The plan says:

Asset Management – build resilience and reduce vulnerabilities while proactively managing the preservation and maintenance of WSDOT’s assets necessary to achieve and sustain a state of good repair.

That’s a fine goal, but the condition of the highway system has been going in the opposite direction. As has become apparent with the recent bridge closures, insufficient preservation and maintenance is diminishing highway system resilience. When highway facilities are closed because of structural deterioration, natural disaster (flood, earthquake, etc.), or accident, it makes travel difficult and often results in increased traffic congestion and more miles driven as people are forced to take long detours. The map below shows WSDOT’s estimate of the detours needed if highway bridges are closed. It isn’t a pretty picture.

The increasing urgency of repairing the state’s bridges and completing seismic upgrades begs the question how that work should be funded. With Washington residents already paying the highest gas prices in the U.S., it seems unlikely the legislature would support another increase in the gas tax. Another jump in license and weight fees, which the legislature raised in 2025, wouldn’t be terribly popular either. But another source of transportation revenue that is already being collected from motorists could help fill the budget gap; that is the carbon emissions revenue that adds about 45 cents per gallon to the price paid at the pump.

The only obstacle is the legislature’s self-imposed prohibition on use of that revenue for highway projects. When the Climate Commitment Act was passed, the bill’s sponsors argued that because their intent was to reduce carbon emissions the revenue raised shouldn’t be used for projects that make driving easier. Whether that was a sensible policy is open to debate, but it needn’t stand in the way of applying the carbon emissions revenue to fixing highway bridges, because keeping them open actually reduces the miles that people drive. Anybody who has doubts need only look at the map above, or ask any of the infuriated residents of Southeast King County who are currently subjected to hour-long detours and worse congestion.

Another benefit of applying the carbon emissions revenue to WSDOT’s billion dollar per year backlog is that it would bring the legislature’s budget priorities into alignment with WSDOT’s aspirational resilience goal, which is unlikely to be otherwise achieved.

If those reasons weren’t enough, there is also fact that failing to adequately preserve state transportation assets results in much higher future costs. For example, when pavement is allowed to deteriorate to the point that complete roadway reconstruction is needed, it costs anywhere from three to five times as much as preventive maintenance. With future highway maintenance liabilities already swelling to the billion-dollar per year level, the legislature can ill-afford to kick the can down the road again.

The 2026 legislative session is expected to be difficult, mostly because the legislature needs to find revenue to fund the expanded programs it approved in recent years. That will involve revisiting priorities and making difficult trade-offs, but using carbon emission revenue to fund desperately needed highway preservation and maintenance shouldn’t be a hard vote. WSDOT’s own data shows it’s practically a no-brainer.