Washington’s Salmon Recovery Office released the 2022 State of Salmon in Watersheds report and the report does a good job of highlighting the status of salmon populations and challenges of helping them recover.

Here are a few things that stood out.

Salmon are still struggling

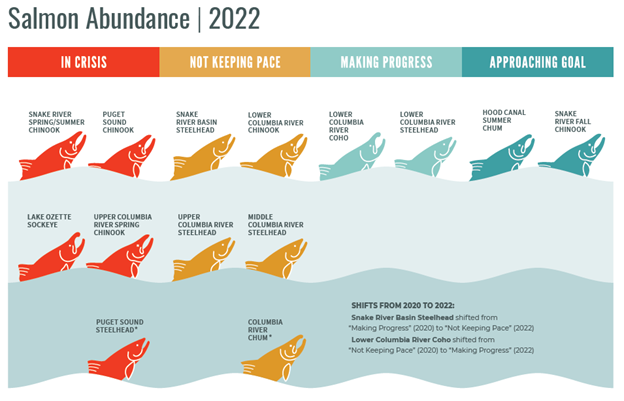

The status of salmon across the state is basically unchanged since the previous report in 2020, with one stock improving and one getting worse. Compared to 2016, however, the status of salmon has declined. Part of the change is that assessments are based on the current status and can reflect near-term changes in ocean conditions and other short-term trends. It does emphasize the need to improve salmon populations so they can survive periods when conditions are unfavorable.

The status of salmon across the state is basically unchanged since the previous report in 2020, with one stock improving and one getting worse. Compared to 2016, however, the status of salmon has declined. Part of the change is that assessments are based on the current status and can reflect near-term changes in ocean conditions and other short-term trends. It does emphasize the need to improve salmon populations so they can survive periods when conditions are unfavorable.

It took decades for salmon populations to decline and it will take decades to recover. It isn’t surprising there isn’t much change in the past two years, but it does highlight the need to take the threat to salmon more seriously.

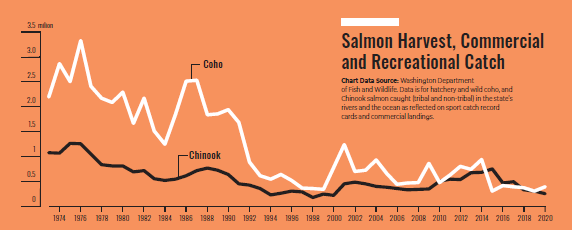

Commercial and recreational salmon harvest levels are fairly low

Occasionally some argue that salmon harvests should be reduced or halted to help salmon recover. As the report notes, commercial and sport catch has declined since the early 1990s. Any further reduction would be close to a ban on harvesting.

Tribes have a treaty right to catch fish, so even if non-tribal harvest was stopped, it would only have a small impact on the overall population.

Seals and sea lions eat a lot of salmon

While the number of fish caught by tribes, commercial, and recreational fishers has declined, the number of fish eaten by seals and sea lions (collectively known as “pinnipeds”) has increased. As the report notes, “Between 1970 and 2015, seals and sea lions increased the amount of adult Chinook salmon they ate from 75 tons to 718 tons – double that of resident killer whales and six times more than the combined commercial and recreational catches.” (emphasis mine). That is remarkable.

The Washington State Academy of Sciences released a study earlier this year arguing the state should begin reducing seal and sea lion populations in key areas. The authors of the report noted that “pinniped predation is considered a primary driver of increasing mortality rates” of salmon. They went on to say that populations of marine mammals may be larger now than pre-settlement. Reducing the population of pinnipeds must be part of any recovery strategy.

Hatcheries play an important role in salmon recovery

The report notes bluntly that “Hatcheries are essential to meet tribal fishing obligations and to provide salmon for commercial and recreational fishing, orcas, and other wildlife.” This is correct and the claims that reducing hatchery production would help wild salmon is speculative and risky. Hatchery managers are taking steps to help ensure hatchery production does not compete with wild salmon. As the report states, “Most hatcheries in Washington that operate in areas with Endangered Species Act-listed salmon and steelhead operate under strict management protocols, known as Hatchery Genetic Management Plans, intended to allow hatcheries to produce young salmon while minimizing impacts to wild salmon.”

There has been an increase in hatchery production in recent years which is positive not only for preventing extirpation of salmon populations but providing fish to harvest for tribes, commercial, and sport fishers.

Private landowners are ahead of the state in opening stream habitat

The report notes that to comply with a court order to remove barriers to salmon habitat the state “fixed more than 100 barriers, opening 474 miles of habitat for salmon,” primarily benefiting coho and steelhead. They estimate an additional $3.6 billion will be needed to meet the court’s deadline.

By way of contrast the notes that “private landowners and state forestland managers in Washington have corrected more than 9,000 barriers.” Most of that was complete a decade ago and some of the habitat that could be opened by those activities is still blocked by the failure of the state to remove barriers downstream.

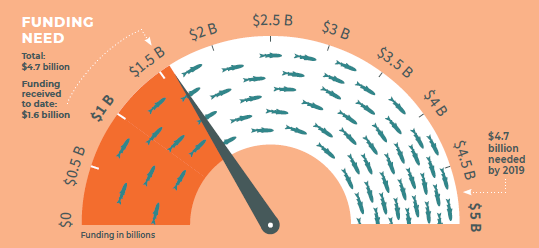

Legislators are not prioritizing salmon recovery

The report argues that one reason we aren’t making progress on recovery is a lack of funding. It notes that a study in 2011 estimated that we would need about $4.7 billion in funding to implement habitat improvement over the decade. Instead, funding was about $1.6 billion. Lamenting the lack of funding is a standard complaint about all government programs, so I have some skepticism about this number. However, it is clear that projects that would help recover salmon have not been funded and the Policy Center has been supportive of increasing funding for salmon recovery projects. The state has the revenue to increase funding but has simply chosen to prioritize other things.