Three takeaways:

Senate Bill 5292 could be a setup: It doesn't raise the tax rate cap for PFML now, but it makes a future cap hike easier to justify.

Not a safety net: Low-wage workers use PFML least.

Fix benefits, not taxes: As solvency fixes are needed for the misguided program that can't pay its way, lawmakers should rein in misuse, repeat use and duration of the benefit.

Most people want their savings and investments to work for them. But majority lawmakers in Washington state want your savings and investments to work for other people — funding paid time off as they start families or address health needs — through the Paid Family and Medical Leave (PFML) program.

A tax rate cap is tied to this overly generous program that benefits many workers who are not in need of taxpayer dependency, while lowering the paychecks of other workers, including some who are in need of taxpayer dependency. But that protective cap of 1.2%, which we’re already close to, may not be in place much longer.

Sentate Bill 5292 makes me nervous — not because it openly raises the cap today, but because it changes the rules in a way that will build the case to raise the cap later. It could be voted on by senators as early as this week.

At first, I thought that as long as the bill didn’t openly attack the rate cap, it might be palatable. That was attempted last year.

In 2025, SB 5292 was sold as a reasonable, technical fix that would change how the PFML tax rate is calculated so it’d be more forward-looking and less volatile. Then House lawmakers amended the bill to raise the cap to 2%. That’s $2 of every $100 in earnings taken from W-2 workers for a benefit they may never see. Full-time workers already pay hundreds to thousands to PFML already. (Calculate your 2026 PFML tax here.)

I worry this year’s strategy is subtler. SB 5292 could quietly rewire the system in a way that makes a future cap increase easier to justify when the fund is again unable to meet its obligations, as projections suggest.

PFML is not a safety net

PFML is funded by payroll premiums taken primarily from workers, with about a quarter paid by employers — money that could otherwise go to wages. The tax rate for 2026 is 1.13%, up from 0.4% in 2019. With a cap of 1.2%, we’re already right up against it.

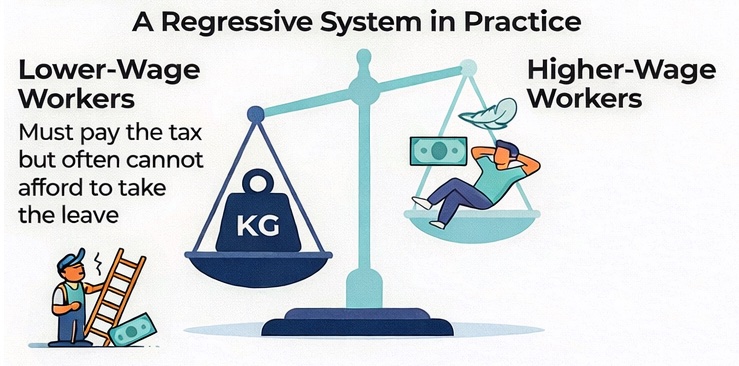

Meanwhile, PFML continues to be marketed as worker protection and safety net — even though the workers least able to afford payroll deductions use the program least. Low-wage workers often don’t meet eligibility requirements tied to work history, and even when they do, the benefit structure doesn’t replace a full paycheck.

Usage patterns should make lawmakers pause before taking even more wages. Employment Security Department numbers show persistently lower participation among the lowest-wage workers. In fiscal year 2025, workers earning $61 or more per hour used PFML more than twice as often as those in the lowest wage group. (Read more about this part of the problem here.)

PFML is progressive in rhetoric, but regressive in reality. The state is taking money from workers least able to spare it to fund a benefit disproportionately used by those with more income and flexibility.

Course collision

SB 5292 proposes two things that matter here. The bill would eliminate the statutory formula used to calculate the PFML premium rate. It also adds a new requirement that rate-setting aim to close the rate collection year with a four-month reserve beginning in 2030, in addition to the existing four-year solvency requirement.

The bill says the premium rate still may not exceed the 1.2% cap — for now. Supporters will point to that and can claim there is no cap increase.

But this structure sets up a future collision. What happens when the program can’t credibly meet both the reserve requirements and solvency expectations within the cap? Lawmakers could claim their hands are tied and the rate must increase to meet legal requirements they created.

If insistent on keeping PFML — as the majority lawmakers seem to be— reforms to PFML should be on the benefit side:

- Limit repeat usage.

- Tighten eligibility where appropriate,

- Reduce maximum duration.

- Address misuse made possible by loose standards.

Sen. Curtis King, R-Yakima, has already introduced solvency-focused bills intended to control costs without raising the cap. Those ideas deserved hearings and serious consideration, but they appear dead this session.

At this point, I think SB 5292 should be treated as presumptively dangerous. Even if it moves “clean” this year, it sets the stage for a cap increase when the new reserve requirement can’t be met.

So here’s my recommendation: If SB 5292 comes to a floor vote, as I think it will, senators should vote no. If it advances, as I think it will, the House should adopt an amendment that explicitly states that failure to meet the reserve target cannot be used as justification to raise the statutory cap.

In other words, if lawmakers want a more forward-looking rate process, fine. They should not be allowed to use that forward-looking process and new reserve requirements as a back door to higher payroll taxes on workers.

Washington workers are already paying 1.13% of wages into PFML. The cap is 1.2%. And the people least able to absorb payroll deductions are among the least likely to use the benefit — while higher earners use it far more. Making the rate even higher should not be a consideration.