Click here to download a PDF of this Policy Note which includes sources and citations

Key Findings

- Approval of a Parks Taxing District would add an 11th public authority imposing taxes on Seattle property owners each year.

- The new Taxing District’s board would be the City Council, a device that would allow Councilmembers to raise property taxes above current state limits.

- Councilmembers could add $337 a year to the tax on a typical $450,000 home. Not all this authority would be used right away. Councilmembers say they would start with a tax of about $148 on a $450,000 home.

- The Parks Taxing District would replace and greatly increase the cost of the expiring six-year parks levy.

- The Taxing District would be permanent. There would be no automatic review or cost adjustment as there is with temporary levies.

- The Parks Taxing District would only exist for raising revenue, not for improving park operations or the way essential services are delivered.

- The money collected through the District would function just like the six-year levy it is intended to replace, with the important difference that voters would no longer have a direct say over whether the special taxes are continued, increased or reduced.

Introduction

Currently people living in Seattle pay property taxes to 10 separate taxing authorities including, for some properties, the Shoreline School District. Seattle Proposition 1 would add an 11th taxing district devoted to funding parks. Currently parks receive funding from the base (regular) property tax residents pay each year and a temporary six-year levy.

The City Council would also be the governing board of the Parks Taxing District. Council-members would be authorized to impose an additional property tax of up to 75 cents per $1,000 of assessed value, or $337 a year for a typical $450,000 home.

The regular city property tax would not be reduced. That financial burden would remain the same, with the usual yearly increases imposed by members of the City Council. In 2013, the city property tax rate was $3.29 per $1,000 of value, or $1,480 on the owner of a typical $450,000 home. State law allows cities to levy a tax of up to $3.60 per $1,000 of value.

If approved by voters, the Parks Taxing District proposal would allow City Council members to impose property taxes above the state legal limit for cities.

The City currently manages a 6,200-acre system consisting of 465 parks, 120 miles of trails, 26 community centers, numerous other recreational facilities and extensive natural areas. The proposed Parks Taxing District is intended to replace and greatly increase the revenues the city collects through an expiring voter-approved parks levy.

This Citizens’ Guide describes the Parks Taxing District proposal, summarizes the powers of its governing board, reviews how it would impact the current property tax burden and gives a short overview of Seattle’s generally rising tax collections. The Parks Taxing District measure will appear on the August 5th primary election ballot.

Powers of the Parks Taxing District

The Parks Taxing District would have the same boundaries as the City of Seattle. The governing board of the Parks Taxing District would be the elected City Council, in effect giving Council-members increased power to impose property tax increases above current limits. Council-members would not be constrained by the state limit of $3.60 per $1,000 of a property’s assessed value each year.

Instead, the Parks District would give them new taxing authority over and above the authority they have now. Councilmembers could impose a tax of up to 75 cents per $1,000 of assessed value, or an added $337 per year on the owner of a home worth $450,000, starting in 2016. The cost to property owners of the temporary six-year levy is about 20 cents per $1,000 of assessed value. Property taxes are also paid by renters, in the form of higher rents collected by building owners.

Councilmembers say they do not intend to use all of the new taxing authority right away. They plan to start by collecting a tax of 33 cents per $1,000 of assessed value, or an added $148 per year on the owner of a $450,000 home.

A new waterfront park is planned as part of the ongoing replacement of the Alaskan Way Viaduct. Urban parks tend to be more expensive to operate and maintain than neighborhood parks. A large share of the increased revenue collected through the Parks Taxing District would likely be used to fund new park facilities along the waterfront, rather than maintaining and improving the City’s system of traditional neighborhood parks.

Higher property tax burden

The proposed Parks Taxing District would start with a property tax burden of roughly twice the level of the special levy it would replace, increasing the total cost from an average of $24 million a year to $48 million a year.

City Councilmembers would also have the authority to reduce the total level of taxation levied though the new Parks District and to allow property owners and renters to keep more of their household income. As a practical matter, it is unlikely City officials would exercise their option to reduce the yearly tax cost of the Parks District.

Over the years, residents in Seattle have experienced frequent property tax increases, but proposals to lower the tax burden are rare or nonexistent. For example, no recent Seattle elected official has run for office on a promise of reducing taxes.

New Taxing District would be permanent

Special levies that fund public services expire after a set period of time, typically six years, giving officials and the public an opportunity to update or retire the added tax burden depending on changing circumstances.

A Parks Taxing District, however, would represent a permanent and continuing form of yearly taxation. In addition, Councilmembers could increase the financial burden at any time without approval by the public.

Initially, the Parks Taxing District would be created by a direct vote of the people. Once in place, however, this action could not be reversed in the same way. The voters’ guide explains:

“The [Parks] District may only be dissolved or its actions reversed by its governing body [the City Council] or a change in state law, but not by local initiative.”

As one news article described it, “Once created, only the board or state law could dissolve the district, not city voters.”

Authority to take private property

The Parks Taxing District would not have the power to force the taking of private land, homes or buildings from unwilling property owners through use of eminent domain. The City of Seattle has the power of eminent domain now. In addition, the City Council, acting as the Taxing District board, could exercise this power on the Park District’s behalf:

“If condemnation of property is required for Seattle Park District purposes, the City may exercise condemnation powers on the Seattle Park District’s behalf.”

A private home, business or other property could be taken if Councilmembers designate it as necessary to serve parks or recreational purposes. The power to take land would not be limited to single homes or properties, but could be applied to groups of homes or to defined areas of existing neighborhoods or businesses.

Citizen concerns about the use of eminent domain power are relevant to the creation of any new governing authority at the local level. National and state court rulings have confirmed the wide extent of eminent domain powers exercised by local jurisdictions. As property owners learned in a case involving the failed Seattle monorail project, local officials can identify, condemn and involuntarily take title to properties for reasons that are only remotely connected to the governing authority’s original purpose.

Imposing local improvement district fees

The Parks Taxing District would not have the power to create a Local Improvement District and levy additional fees on property owners, but City Councilmembers could exercise this power on the District’s behalf:

“If formation of a local improvement district is required for the Seattle Park District purposes, the City may carry out the formation and may levy and collect assessments on the Seattle Park District’s behalf.”

Additional pay for Councilmembers acting as Park Commissioners

State law allows Park Commissioners to receive payment of up to $90 a day, adjusted for inflation since 2008, or about $99 in today’s dollars, up to an inflation-adjusted $9,513 a year. City Councilmembers say they will not collect this additional compensation, and have added a waiver to that effect to the interlocal agreement that describes how they intend to govern the Parks Taxing District.

This means Councilmembers would receive no additional pay when they act as Park Commissioners. The interlocal agreement, however, could be changed at any time by agreement between Councilmembers and the Mayor, without receiving voter approval. As a practical matter, using Parks District authority to supplement Councilmember pay would be extremely unpopular and is unlikely to occur.

Replacing General Fund parks spending

Parks supporters are concerned the City Council would use the new revenue they collect with the Parks Taxing District to replace, rather than supplement, the current level of General Fund spending on the City’s parks program. The worry is that Councilmembers will cut one dollar of General Funding spending on parks for every new dollar they collect through the Parks Taxing District.

In response, Councilmembers say they are committed to maintaining the current level of General Fund spending on parks. In making this commitment, however, Councilmembers provided themselves with two important exceptions.

First, the City Council says it would only maintain General Fund parks funding based on the current annual level of $89 million plus inflation. Typically, government spending rises faster than inflation, so over time the parks program would likely receive less money each year compared to spending increases in other areas of the budget. In other contexts, not increasing spending on a particular public program as fast as the overall budget is called a “cut.”

Second, the City Council says that by a three-fourths vote it could decide that “a natural disaster or exigent economic circumstances” could prevent it from providing the promised level of general funding to the parks program. Both terms would be interpreted by Councilmembers themselves.

A “natural disaster” designation could involve diverting parks funding to snow removal or routine clean-up after a windstorm. Councilmembers could view an “exigent economic circumstance” as an unexpected slowing in the rate of tax revenue increase or a period of mild economic recession. Either exception could be cited as a reason for reducing General Fund spending on parks, shifting more of the financial burden to the Parks Taxing District.

Staffing, contracting and administrative costs

The Parks Taxing District would exist only on paper, it would have no facilities, employees or contracting authority.

“The City shall maintain, operate and improve its parks, community centers, pools and other recreation facilities, and shall provide recreational programs, on behalf of itself acting in conjunction with the Seattle Park District.”

“The City shall provide the staff and other resources to implement the projects, programs and service identified in the adopted Seattle Park District budget.”

The City Director of Finance would serve as the Treasurer of the Parks Taxing District. All parks and recreation land, facilities and equipment would remain the property of the City, and no joint property ownership or management would be contemplated.

The Parks District would be barred from contracting out, inviting competitive bids or providing access to public work for Seattle businesses. The Parks District would not be used to improve park operations, lower costs or enhance the quality of services delivered to the public.

“The Seattle Park District shall not contract for the implementation of projects, programs or services with any person other than the City.”

The Mayor would submit the Parks Taxing District budget to the City Council based on a six-year funding cycle. The money collected through the District would function just like the six-year levy it is intended to replace, with the important difference that voters would no longer have a direct say over whether the special taxes are continued, increased or reduced.

Rise in Seattle property tax collections

Seattle officials continue to benefit from windfall revenues created by a gradually improving local economy. As the City’s report on the 2014 budget reports:

“City revenue grew at a rate not seen since the onset of the Great Recession. The new forecast reflected better than anticipated results for 2013 sales tax revenue and projected an additional $1.5 million would be available in the General Fund.”

Property tax collections have risen faster than inflation each year since 2012 and are expected to hit record levels in 2014, based on an expected 9.5 percent growth in the value of assessed properties subject to tax.

Current special tax levies

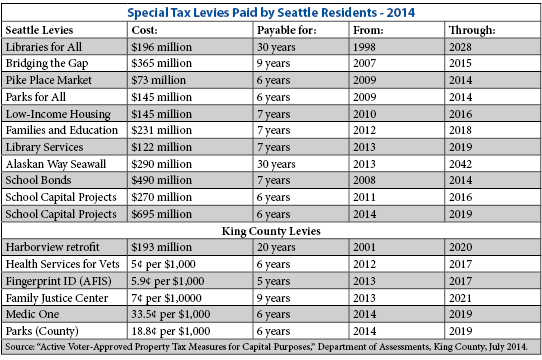

Residents in Seattle are paying 17 special tax and bond levies through City government, the Seattle School District and King County, in addition to the regular property tax.

The City of Seattle administers eight of these special tax levies. Seattle officials use more special levies to fund basic government services than any other city or county in the state.

The total annual property tax burden is built into the cost of occupying private homes, apartment or commercial buildings within Seattle city limits. The high level of taxation contributes the high cost of living in the city, with the burden falling hardest on low income people, working families and elderly residents living on fixed incomes.

Some homeowners have paid far more in property taxes over the years than the original purchase price of their home. The taxes are also paid by businesses that lease property and by apartment dwellers who pay higher monthly rent.

Some special levies are due to expire in 2014, but the overall financial burden will continue to rise. New costs that might be added soon include the Bridging the Gap II levy, a new Low-Income Housing levy, a new Universal Pre-School program and Mayor Murray’s plan to fund current bus service with added taxes and fees.

The table below shows the 17 city, school district and county special tax levies paid by Seattle residents.

Strong sales tax revenue growth

Seattle officials have benefitted in recent years from strong growth in sales tax revenue, providing added money to fund public services.

Sales tax revenue has grown by 6 percent to 8 percent annually since 2010, and increases are expected to continue through 2014, in 2015 and beyond. The recent growth in the amount of sales tax money City officials collect from consumers has increased at about three times the rate of inflation in each of the last three years (2011, 2012, 2013).

Rise in other revenue sources

Other areas of strong revenue growth for City officials are the Business and Occupation Tax, the Admissions Tax, the Real Estate Excise Tax, the Public Utility Tax, and the Commercial Parking Tax. City officials expect to collect additional business tax revenue from the legalized sale of marijuana, adding some $250,000 a year to city coffers. Together these revenue sources show year-over-year growth rates of 3 percent to 4 percent, a rate significantly greater than inflation.

Overall, the $1 billion General Fund managed by City officials has been increasing annually by 3.5 percent, a growth rate that is faster than inflation.

Rise in executive salaries

While city leaders seek to raise the tax burden on citizens, they continue to adopt policies that increase city costs, including significant recent increases in the executive salaries provided by taxpayers (overall, Seattle has over 10,000 public employees).

For example, in June City Councilmembers, at the request of Mayor Ed Murray, approved a new pay scale for city executives. City leaders authorized an additional $120,000 a year to the city’s highest-paid executive, City Light chief Jorge Carrasco, potentially increasing his pay to $364,000 a year. Initially, his pay would be increased by $60,000 to an annual salary of $304,000.

Six other executives will receive over $200,000 each per year under the pay increases approved by the Council. The exact amounts will be set by Mayor Murray. The pay increases will be funded by residents through monthly household and business electricity bills. The raises are effective July 1, 2014.

Conclusion

As laid out in the interlocal agreement, all the normal services needed to maintain city parks would be managed and provided by the City, as they are now. The proposed Parks Taxing District would have no other purpose than to provide city officials with a way to collect more property tax money from Seattle residents.

The new Taxing District would function as a device for raising Seattle’s yearly property tax burden beyond the limits provided in state law. Once officials are close to the tax limit for one taxing district, in this case the City of Seattle, they can start with a new limit by proposing the creation of another taxing district. The separate tax limits apply to separate districts, but when all the annual levies are added together they are applied to individual property owners and must be paid from the single income of each family or business.

The cumulative tax burden thus adds up to far more than the property tax imposed by any one district. The creation of a Parks Taxing District would continue this cumulative trend, adding an 11th district to the jurisdictions that already tax Seattle property owners.

The proposed District is only a funding mechanism. The ballot measure proposes no reforms or improvements to the operation of city parks or to services provided to the public. The Parks Taxing District proposal would double the property tax burden for parks and make that burden permanent, while doing nothing to improve the way an essential public service is delivered. Increased revenues would likely be used in an effort to reduce the Parks Department’s extensive maintenance backlog, but management of the system itself would remain unchanged.