On November 14th the on-line news outlet Politico reported the Trump Administration has drafted a proposal that would end the use of Federal Highway Trust Fund revenue for transit purposes. As you would expect, even the rumor of such a proposal set off howls of protest from organizations that have benefited from billions of dollars in Federal transit subsidies.

The proposal, which has not been publicly released, is said to consist of two main elements. The first would terminate the Mass Transit Account within the Highway Trust Fund, the second element would end the ability to flex highway funding for transit projects.

The Highway Trust Fund was created in 1953 to fund construction of the interstate highway system. It was funded by an increase in the federal gas tax which was raised from two cents per gallon to three cents per gallon. In subsequent years the tax rate was increased and today it stands at 18.4 cents per gallon for gasoline and 24.4 cents per gallon for diesel fuel. In 1982 the Fund was expanded to include a Mass Transit Account which receives about 20% of the Fund’s tax revenue. The Trust Fund, which was originally restricted to highway purposes, also began to allow state’s the ability to use Federal highway funds for transit purposes.

Opponents of the proposal point out the Trust Fund is facing insolvency and that eliminating transit funding would not be enough to solve that problem. The larger problem is that congress has found it convenient to spend far more than the Trust Fund is taking in, resulting in large deficits, so large the Trust Fund will become insolvent in 2028 unless funding is increased or spending is reduced. So while it is true that eliminating transit funding wouldn’t, by itself, solve the Fund’s problem, it would make the deficit smaller.

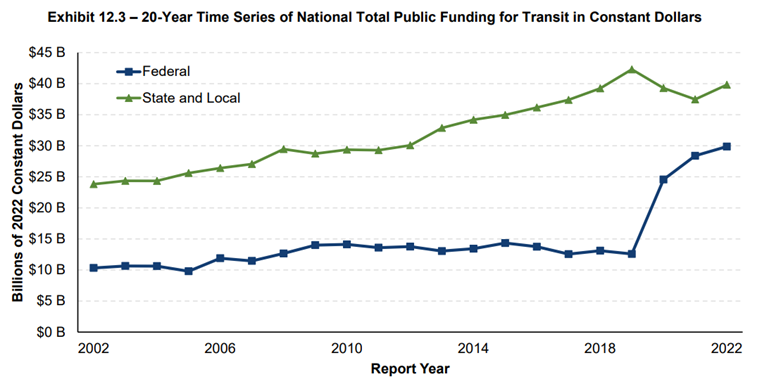

The question that should be asked is whether continued Federal transit subsidies are really solving transit’s problem. We can get a sense of that from looking at funding, ridership, and cost trends. What the data shows is that ridership is lower today than it was ten years ago despite a very large increase in subsidy. The graph below shows the increase in transit funding from Federal and state/local sources. The total, which increased rapidly during the COVID pandemic, now exceeds $70 billion per year.

In contrast to the increase in funding, ridership has decreased. Total transit ridership in Washington is about 20% lower today than it was ten years ago. The drop-off that began during the pandemic contributed to that, but for most agencies in the state ridership had been trending downward for years before the pandemic. If an increase in subsidy was the solution to transit’s performance problems the large increase in spending on transit would have produced better results, but the data shows otherwise. Cost have gone up, ridership has gone down.

Discontinuation of Federal transit subsidies would only reduce total transit funding by about 17% (depending on what year is chosen as baseline), and most of that is for capital projects rather than operating expenses. For some agencies the reduction in Federal funding would necessitate re-evaluation of their services and revisions to their long-range plans. Given ridership and cost trends that type of re-evaluation is very much needed in any case.

For example, the Sound Transit plan is based on the very optimistic assumption that more than eight billion dollars in Federal grants will be available to fund construction of light rail extensions. But as Sound Transit has admitted, even with Federal subsidies the budget gap is so large the projects are not affordable. If billions of dollars in Federal grants aren’t enough then it is definitely time for Sound Transit to seriously look at much more cost-effective alternatives to light rail. The low ridership, high costs and neighborhood impacts of light rail wouldn’t be fixed by Federal funding even if the assumed billions of dollars were available.

During COVID most transit agencies used the unprecedented windfall of Federal funding to continue running existing routes even when ridership had all but evaporated. Now that it has become clear working from home and e-commerce have permanently shifted travel demand, transit agencies need to re-examine their plans and figure out what services can be economically provided.

Aside from the question of whether continued Federal transit subsidies produce a positive return on investment, the fundamental question that congress needs to consider is how the Highway Trust Fund can be structured to ensure the Federal investment in the National Highway System is adequately maintained. In Washington alone it is estimated fully funding highway preservation and maintenance would require an additional billion dollars a year. As a recipient of Highway Trust Fund dollars WSDOT is legally obligated to maintain our state’s National Highway System infrastructure, including interstate freeways, but state transportation budgets have failed to do so. Returning the Highway Trust Fund to its original purpose would help states focus resources on high-priority highway maintenance that is long overdue.

At this early stage of the process it is hard to know what will become of the Administration's proposal, but at the very least it should start a discussion about national transportation priorities that has been neglected for too long.