This year, I have had the privilege of being a volunteer participant in the state’s Road Usage Charge (RUC) Pilot Project, led by the Washington State Transportation Commission (WSTC).

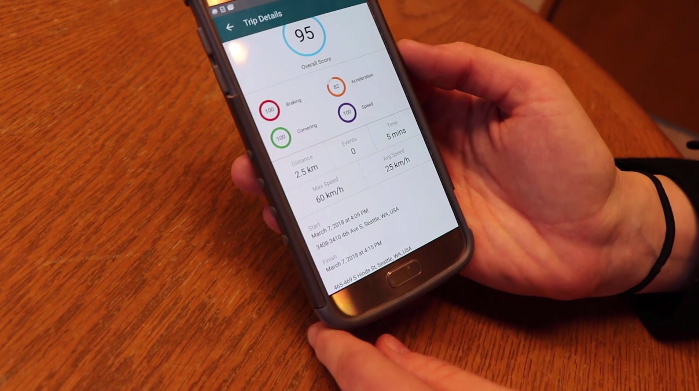

I have tried what I believe is the most invasive of the mileage reporting methods (the controversial GPS-enabled transponder installed in my car) and recently switched to a less invasive method (the odometer reading).

I wanted to experience the pilot for myself, in a way that would hopefully help inform my view of what this would look like should it become policy. To be clear, there is a significant difference between the pilot and the potential policy, which I want to outline here.

The Pilot

The pilot is an isolated experiment where volunteers receive simulated invoices based on a flat charge of 2.4 cents per mile driven on public roads. Drivers are credited for the fuel tax they supposedly pay, and the remaining balance is what they would hypothetically owe. Those with electric or fuel-efficient vehicles would owe more than those whose vehicles are less fuel-efficient.

Drivers have five reporting options (mileage permit, odometer charge, non-GPS or GPS-enabled transponder, or smartphone app).

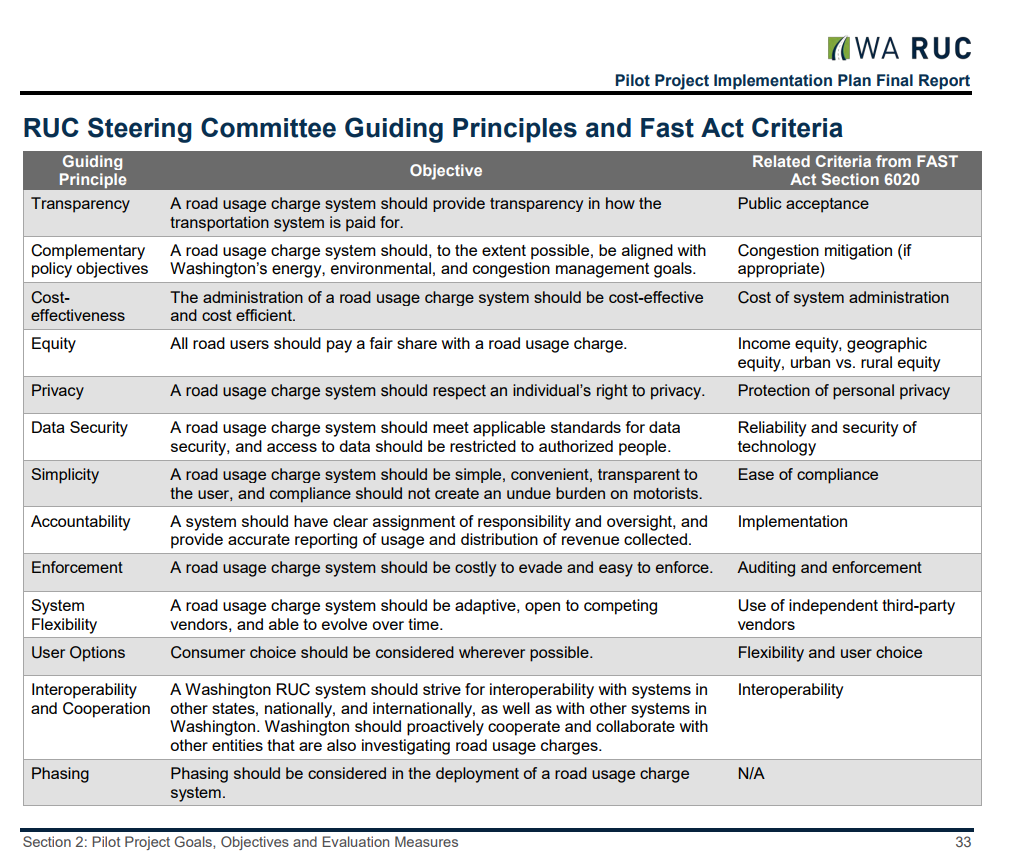

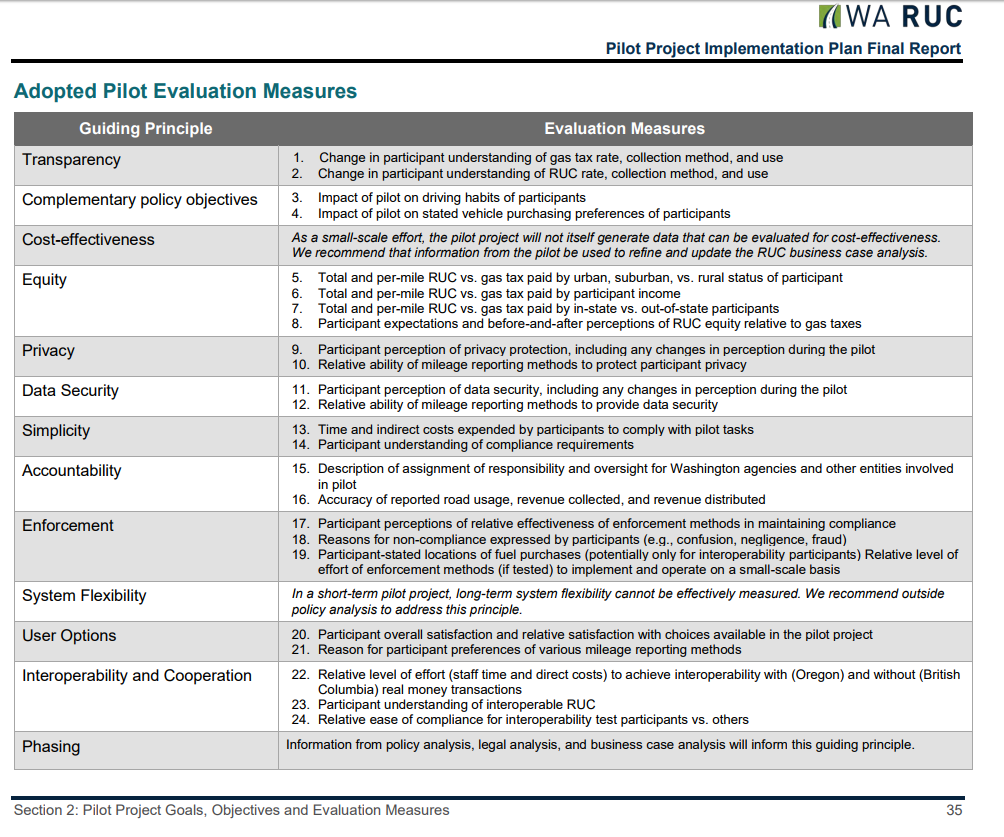

The pilot concludes this year, and the WSTC and RUC Steering Committee will produce their assessment in 2019. The assessment will be measured against guiding principles and evaluation measures set by the RUC Steering Committee.

The principles can be found on page 33 of this report, and include things like transparency, privacy, simplicity, enforcement, and interoperability.

Some of the objectives under the principles category that stand out include:

- A road usage charge should, to the extent possible, be aligned with Washington’s energy, environmental, and congestion management goals.

- A road usage charge system should respect an individual’s right to privacy.

- A road usage charge system should be costly to evade and easy to enforce.

The evaluation measures can be found on page 35 of the same report.

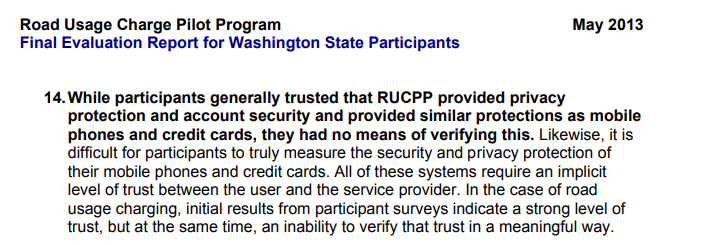

Many of the evaluation measures depend on participant perception and satisfaction. For example, a couple evaluation measures look at perception of privacy protection and data security. As we know from Washington’s past participation in a Road Usage Charge Pilot Program under the direction of the USDOT, “While participants generally trusted that [the pilot] provided privacy protection and account security and provided similar protections as mobile phones and credit cards, they had no means of verifying this.” From the report:

Perception of security is meaningless without exposure to real evidence and data. If the assessment of the pilot’s success hinges on public satisfaction or perception, which can be manipulated, and eliminates very real policy variables from the discussion - then the pilot will undoubtedly be called a tremendous success.

Thus, although I am interested in the technical process of submitting mileage and how legitimately eerie it does feel to be tracked, I am primarily concerned what this could transform into should it become state policy.

The Policy

This is why I have focused on what a RUC would look like in practice, after its journey through what will surely be a messy and contentious political process.

In general, mileage-based user fees are seen by many transportation analysts as a fair and even ideal way to pay for the use of roads. The tool works or is technically feasible. However, the tool in the wrong hands is certain to worsen the problem public officials say they want to solve – namely the funding and maintenance of our road system. Used for spending unrelated to roads, a Road Usage Charge is not a user fee, but a mileage tax.

We already know that the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC), in their update to Transportation 2040, are counting on $40 billion in new taxes, fees and tolls from the traveling public. Combined with current revenues, that’s $196.8 billion over roughly two decades. Of the $40 billion in new revenue, officials want 70% to come from the Road Usage Charge. They would like to see 53% of spending go toward transit, and 17% toward highways.

If a Road Usage Charge is implemented – the PSRC notes they would like “a broader consideration of possible uses" (they don’t want the charge to be protected by the 18th amendment like the state gas tax is for highway purposes only). This would allow officials to spend the money on what they feel is best for us rather than on actual public demand, a concern we have highlighted repeatedly. If the PSRC and like-minded elected officials get what they want, the charge will not be a true user fee but a tax, and less money could go to roads.

This is a major policy concern.

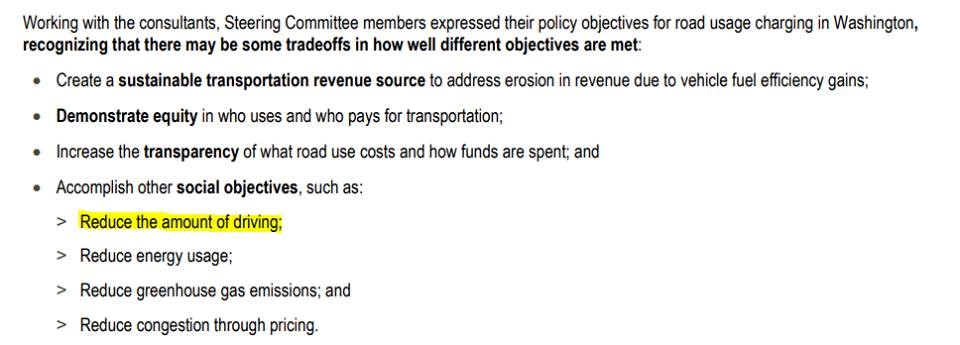

Additionally, social policy objectives and discussions around the pilot suggest a mileage tax can be used to change driving behavior, which would be in line with current state law that recommends a 50% reduction in per capita driving by 2050. However, any reduction in driving would reduce either fuel or RUC revenue, meaning this state policy conflicts with the RUC objective to generate more revenue than the fuel tax.

While it is not intended for a RUC to conflict with policies the legislature has enacted, but to align with them, I don’t feel a lot of hope for this policy conflict to be resolved in a way that is favorable for the public. I only see two ways for a RUC to not undermine state driving reduction targets, which are questionable to begin with. First, lawmakers could make the rate progressively higher, perhaps by indexing it to inflation, eliminating any need for future votes on rate increases. Second, they could impose a carbon tax to make driving a gas-guzzler less attractive as a means of escaping payment of a higher mileage tax (which is intended to capture dollars from more fuel-efficient vehicles). What people would be left with is either paying a very high fuel tax (inclusive of a carbon tax), or a very high mileage tax.

The 18th amendment debate, as well as social objectives of a potential mileage tax, have policy implications that could fundamentally eliminate the possibility of a true mileage-based user fee, allowing government to collect and spend public money from drivers the way they believe is best. Even more concerning is the great social cost the public would pay in the form of reduced privacy, autonomy, and mobility.

A Road Usage Charge, as a policy in Washington state, is likely to be ineffective as a true user fee. This, to me, is far more important than the pilot itself.