Throughout the heated debates over the controversial mandated $15 minimum wage, opponents have asked “why $15?”

Supporters contend a higher minimum wage will put more money into the wallets of workers, which those workers will spend, thereby stimulating the economy and creating jobs. So would it not follow that giving workers even more money, say a $20 or $25 minimum wage, would be even more beneficial? Why settle for just $15 if $25 would really get the economy rolling?

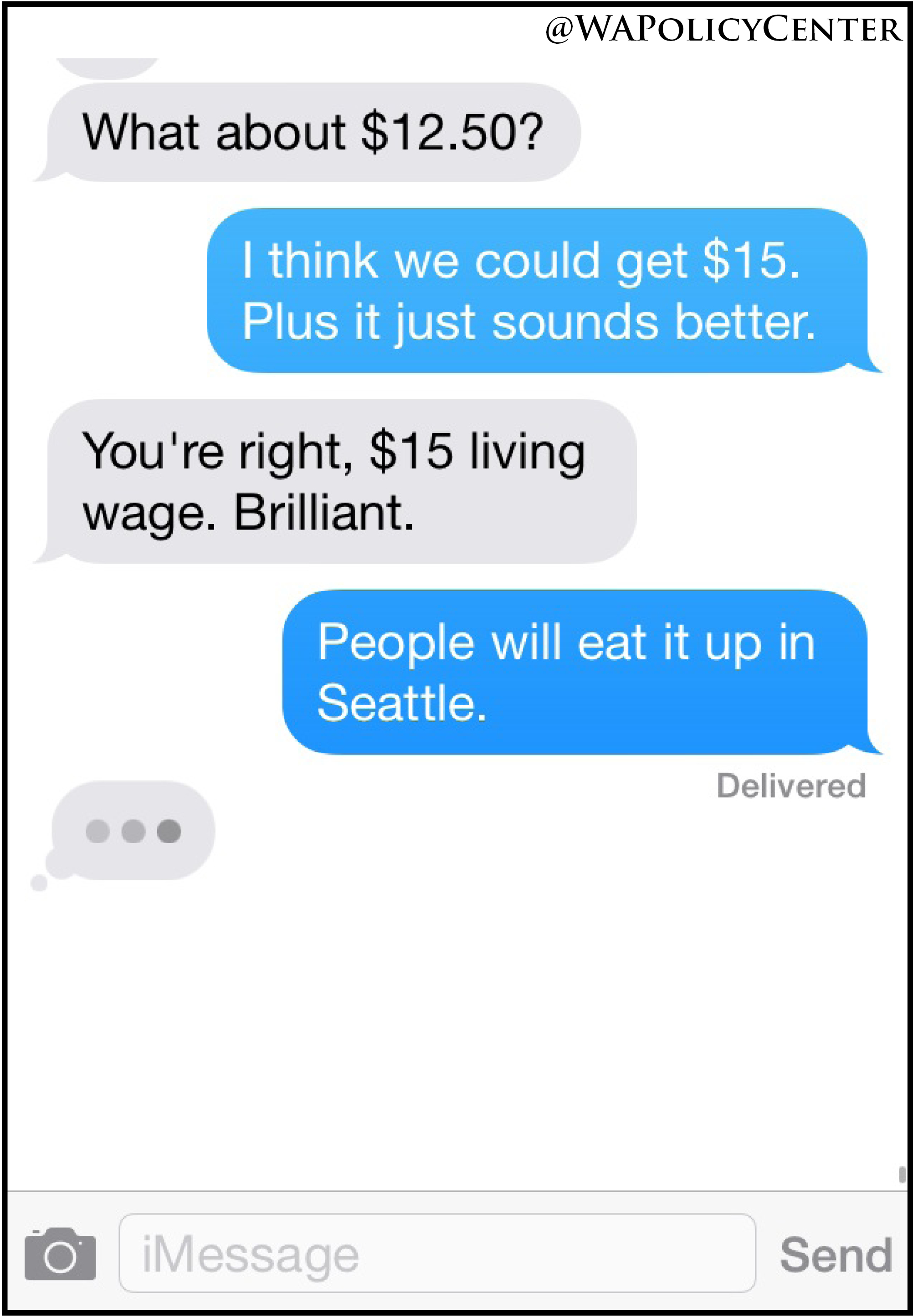

The reason supporters settled on $15 has nothing to do with math, data, the economy or supply and demand. It’s about politics.

The biggest supporters of a mandated $15 minimum wage, labor unions, admit it was a political decision. The number simply had to be big enough to motivate workers to enthusiastically campaign for it, but not so big that it would not be taken seriously.

As the political director for socialist City Council member Kshama Sawant told The Seattle Times:

“Support for $15 exists not because people have done the math and said gee this is what the minimum wage should be.”

Support for a mandated $15 wage exists because deep-pocketed labor unions hired a team of powerhouse campaign strategists, political consultants and public relations experts to message and spin a $15 wage to appeal to the public. One union spent more than $11 million last year on the national campaign, with more than $1 million going to a PR firm. It is not supply and demand that determined $15 is the minimum wage all workers should earn, even those with no experience or who perform poorly; it was focus groups and opinion polls.

The fact is many supporters of a higher minimum wage say $15 is not nearly enough, that workers should earn as much as $21 per hour. So $15 per hour is their compromise.

While the activists pushing a mandated $15 wage did not rely on any mathematical or economic research to decide that the wage for every worker should be at least $15 per hour, there is plenty of research on the consequences of forcing employers to pay such an artificially high wage.

Professor Arindrajit Dube, an economics professor at the University of Massachusetts, actively supports a “modestly higher wage” than the current federal wage of $7.25. He says while a modest increase does not harm employment, a radical increase to $15 an hour could hurt employment and increase prices:

“Would I be concerned about possible job losses if there were a $15 minimum wage in the restaurant industry, yes, I’d be concerned.”

Other notable economists share Dube’s concern. Professor David Neumark, an economics professor at University of California, Irvine, has spent years researching the impact of minimum wage increases, especially on employment. Neumark estimates a $15 minimum wage would reduce employment in industries like fast food by 5% to 6%:

“Anyone who thinks sensibly about this should be concerned that $15 would have a big effect on employment.”

An economist with the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Daniel Aaronson, says every 10% increase in the minimum wage increases prices by about one percent:

“One of the cleanest results I’ve ever found in my research career is that prices definitely go up.”

Studies by Barry Hirsch, an economics professor at the Georgia State University, show the price increases can be much greater. Studying the impact of the 41% increase in the federal minimum wage from 2007 to 2009, Hirsch found 81 fast food restaurants increased their prices by an average of nearly 11% in response to the increase.

Of course, most economists say there is no way to tell what the real impacts will be in Seattle because the city’s 60% increase is unprecedented. “I hope they do it, because we’d love to study the results,” said Professor Hirsch.