The taxpayer-funded report on destroying the Snake River dams closed the comment period yesterday. While there are some good insights, the report is clearly skewed toward destroying the dams and many of the sources cited on key issues like energy are paid-for by left-wing environmental groups.

Here are the comments I submitted responding to the report. Additionally, you can read my colleague Pam Lewison's comments about the impact destroying the dams would have on agriculture. I also submitted a separate comment about one particular error in the report regarding salmon survival on the Snake River compared to other West Coast rivers. You can read that here.

Salmon Returns

In several places, the report assumes Spring Chinook returns are “declining.” For example:

- “Despite these efforts, salmon abundance continues to decline.” – p. 1-2

- “Snake River salmon populations are projected to continue declining.” p. 4

- “Snake River salmon populations are expected to continue to decline.” p. 14

- “Despite these efforts, salmon continue to decline.” p. 20

- “All of these threats likely have contributed to the decline of salmon runs in the Snake River.” – p. 21

None of these sentences – none – have a source citation to defend this claim, which is central to the justification for destroying the dams. Indeed, even though it was relatively low compared to the past two decades, the Spring/Summer Chinook run in 2021 was still larger than any run at Lower Granite prior to the year 2001. It was larger than any run at Ice Harbor Dam between 1970 and 2001. This does not account for the highest return years between 2009-2016, all of which are higher than any runs since 1962. Currently, the 2022 Spring/Summer Chinook run is more than 30% above the 10-year average, and is the third year in a row with increased returns.

At the very least, the report should acknowledge that salmon returns over the past two decades have been significantly higher than in the previous four decades and the language of “continuing to decline” should be removed since it is not accurate in context of the last 60 years.

The one source for the claim is a chart on page 21 showing rough estimates of “Historic abundance” with the insinuation that the cause of these declines is the Snake River dams. There two major problems with this insinuation.

First, the numbers are contradicted by the charts on page 24 which show the population of Spring/Summer Chinook in 1962 – when the first dam was completed – to be around 60,000, not the 1 million listed on page 21. Even assuming that the period of construction impacted salmon runs, the use of 1 million as a baseline is misleading and exaggerates the population just prior to dam construction.

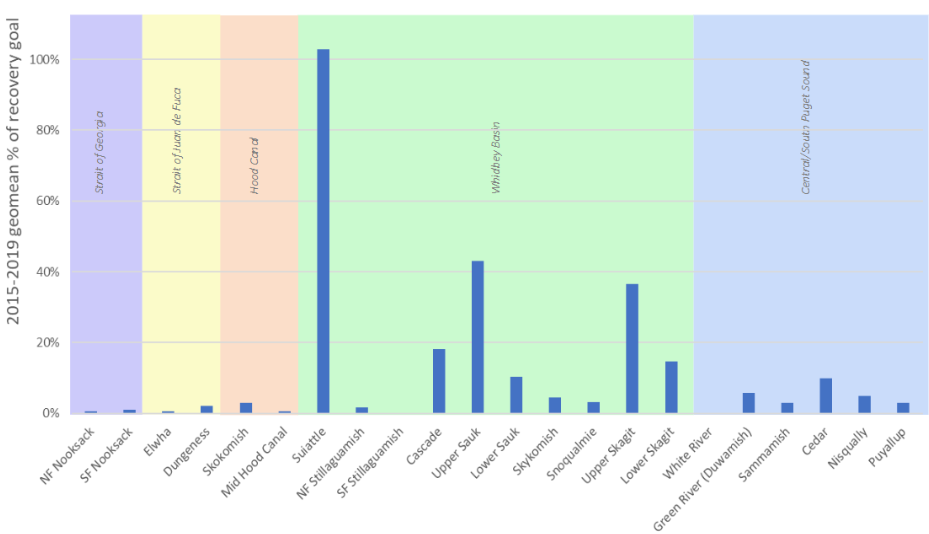

Second, there is no watershed in the Northwest at “historic” levels – with or without dams. If the metric for taking action is getting to “historic” levels, then the report must explain why destroying the dams is more important than action in other watersheds. As the Puget Sound Partnership notes, salmon runs in the Salish Sea are a tiny fraction of recovery levels – which is significantly below historic levels.

Why should we spend $33 billion on the Snake rather than other places? If historic abundance is the metric, it contradicts the report’s focus on only the Snake River dams since the threats in other watersheds are even more dire.

The response is likely to be “this report only focuses on the Snake River.” Exactly. A myopic focus on the Snake is distracting from the work that needs to be done across the region, draining resources from other watersheds in crisis. A myopic focus on the Snake is irresponsible.

In other places, claims are made about the Columbia River system as a whole as a surrogate for Snake River populations. For example, on page 3, the report says “…the total abundance of salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River is at or near the level it was when the first Endangered Species Act (ESA) listings were registered in the mid-1990s.” Why ignore the Snake River data when they are readily available? As the Snake River data show, the claim that salmon abundance is the same as in the mid-1990s is not true for Snake River salmon, for wild salmon or all salmon. The 10-year average returns are significantly higher than for the 1990s.

Similarly, on page 4, the report notes, “From 2010 to 2019 the Pacific commercial salmon fishery saw a decrease of 41% in commercial revenues in real terms and a 64% decrease in commercial landings.”

First, there is no indication of how the Snake River runs impacted this total. Second, it is a good indication that the low salmon runs in 2019 were a region-wide phenomenon. This contradicts the report’s insinuation that the Snake River dams were responsible for low runs in 2019, indicating that ocean conditions, harvest, and other factors beyond the Snake River were key factors driving those numbers.

Use Snake River data and remove potentially misleading references to Columbia River populations.

On page 21, the report claims, “While many salmon populations on the West Coast are not meeting these SAR goals, the SARs of Snake River salmon are among the lowest.” We commented separately on this issue but want to reiterate that the source the report cites for this claim says the opposite, noting that “the SARs of Snake River populations, often singled out as exemplars of poor survival, are unexceptional and in fact higher than estimates reported from many other regions of the west coast lacking dams.” Rather than showing that Snake River SARs are “among the lowest,” the study specifically concludes they are “unexceptional.” Their data show that Snake River SARs using coded wire tag (CWT) data are very similar to other rivers across the West.

Finally, the focus only on wild salmon when it comes to populations contradicts the report’s inclusion of recreational and other harvest values elsewhere. For example, on page 78 the report asserts that “investments could provide significantly improved recreational opportunities compared to the existing system through increased recreational, sportfishing…” and other benefits. Sportfishing relies entirely on hatchery salmon. Allowable catch as determined by state agencies is set based on total salmon population, not just wild salmon.

If the report is going to recognize the value of hatchery fish when it comes to potential economic benefits of recreation, it should also acknowledge that the total salmon population on the Snake – wild and hatchery – is much better than it was 60 years ago. Additionally, it argues against only including wild salmon in the charts included in the report.

Energy

On page 65, the report notes that “If the LSRD were to be breached, the replacement portfolio needs to be in place and demonstrating that it is producing energy and providing services to the grid before the dams were breached.” It goes on to say the risks include, “the reduction in peaking capacity, risk of congested transmission lines particularly near the Tri-Cities, increased power rates, and potential increases in carbon emissions due to increased emitting generation to compensate for the loss in capacity.” Any replacement should leave the Northwest no worse off than the existing portfolio with the Snake River dams. Electricity demand is increasing and reducing total generation increases the risk of blackouts and other disruptions, as well as increasing the likelihood of price spikes as supply fails to keep up with growing demand.

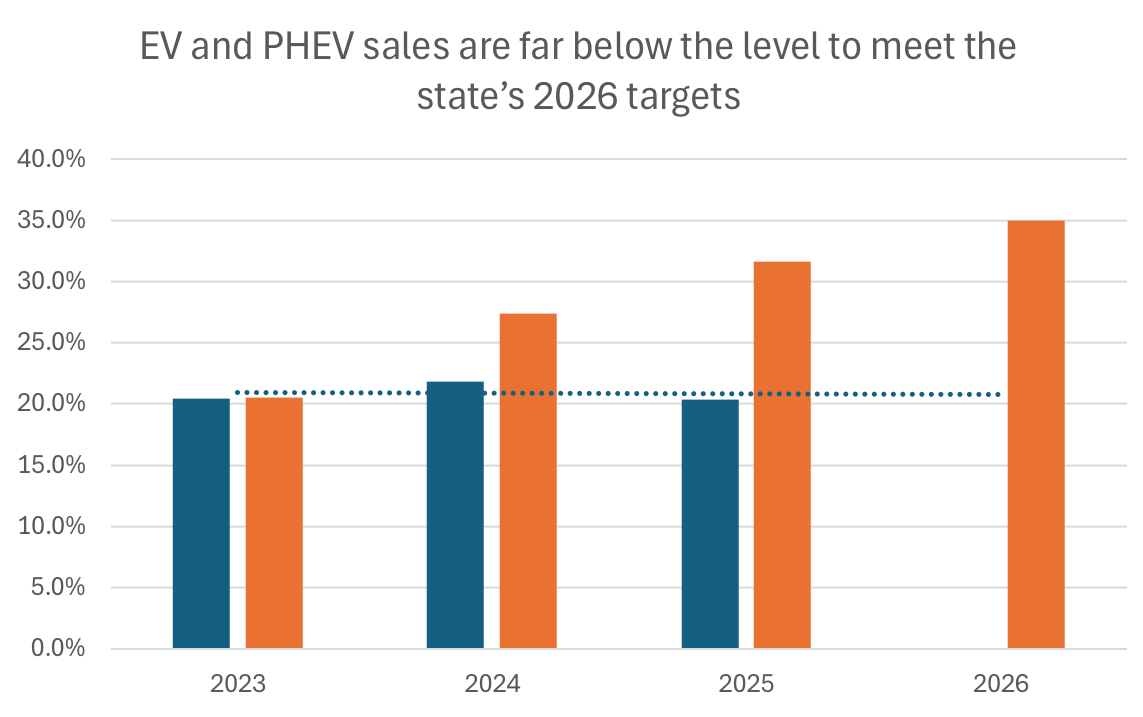

The report then says, “the replacement portfolio does not necessarily need to be a one-to-one replacement of the current services provided by the LSRD,” going on to say, “some experts believe” that we could replace the energy from the dams with an “optimized portfolio” that meets the needs of the system “year-round.” This is extremely dangerous. Demand for electricity in Washington state is set to increase dramatically over the next decade and replacing only a portion of the energy is extremely risky.

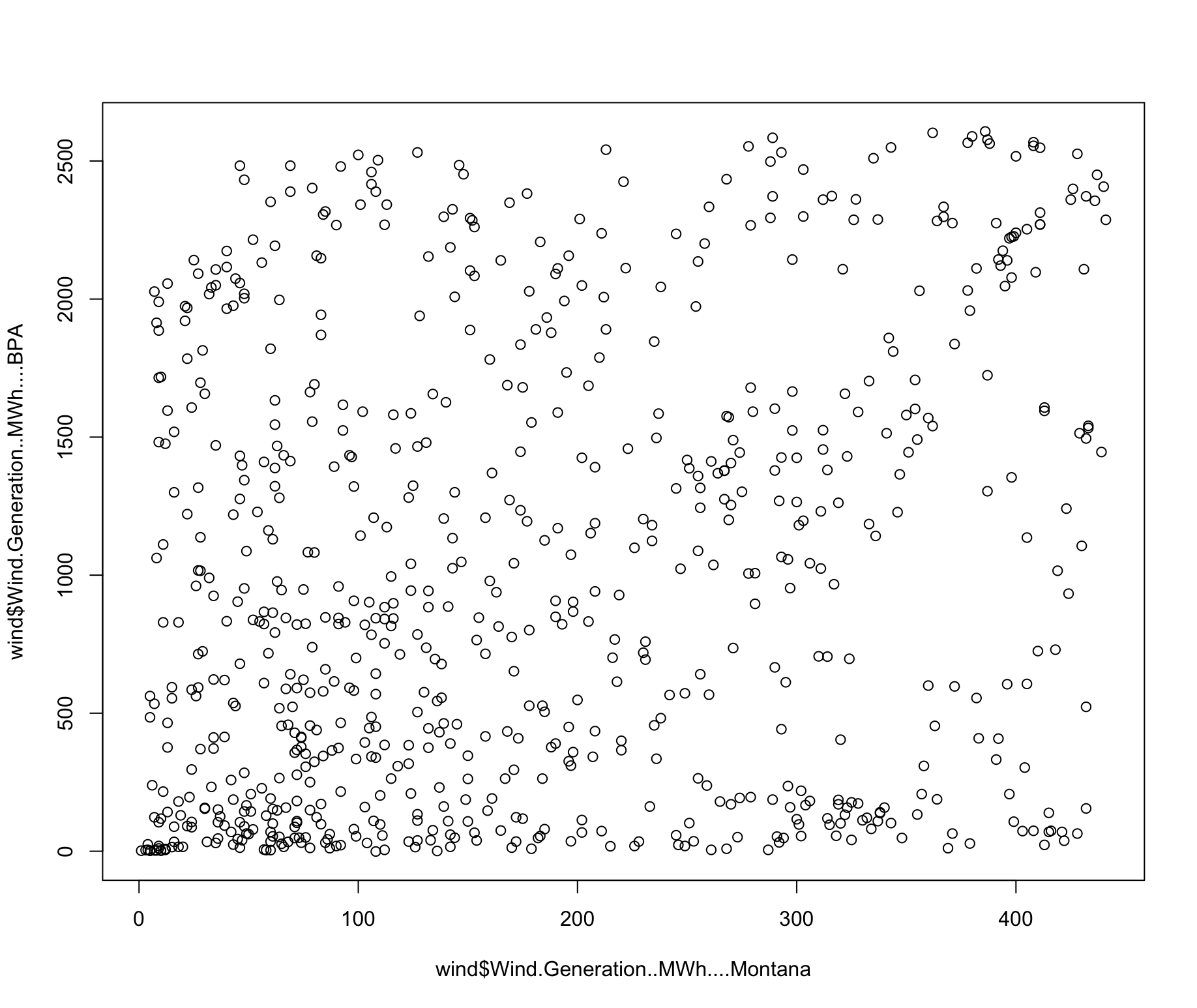

Although the experts are unnamed and there is no source citation for the claim in the report, one proposal that has been discussed is to replace the dams with a combination of wind power from Montana and the Pacific Northwest. For some parts of the year, wind power in Montana complements PNW wind by blowing at different times. But there are numerous occasions where there is little or no wind in either region. A look at wind production from both regions for all of 2021 finds many days (indicated in the lower-left corner of the included graphic) where there is virtually no wind. Even if Montana wind appeared to be a good replacement for power from the LSRD dams “year-round,” during these periods of time, there would be a significant increase in the risk of blackouts. Any plan to replace the dams with wind must account for how these periods of extremely low wind production will be handled.

On page 66, the report notes that when “market purchases” are included, the shortfall from the destruction of the dams is smaller. Two key points should be acknowledged by the report.

On page 66, the report notes that when “market purchases” are included, the shortfall from the destruction of the dams is smaller. Two key points should be acknowledged by the report.

First, “market purchases” is often a euphemism for electricity produced by natural gas from out of the region. The 2018 NWEC study specifically acknowledges this. So too does PNNL research on increased demand for electricity in the upcoming decade. For instance, the PNNL report on energy adequacy to meet increased demand due to increased EV sales notes that additional generation needed to meet that demand, “is likely to be provided by natural gas cycle plants and combustion turbine predominantly throughout the WECC.” The report should acknowledge that this would increase CO2 emissions.

Second, as demand increases for electricity due to the electrification of transportation and buildings, the prices on the market will go up significantly. The PNNL study on EVs alone notes that in the summer, prices during peak hours could double with the Snake River dams in place. Removing those dams would drive prices higher.

As the report notes on page 68, “the peaking capabilities of the LSRD are the hardest to replace with existing technologies.” Eliminating the ability to provide energy during peak demand is increasingly risky at a time when PNNL and others note that demand during these hours is likely to increase significantly.

On page 67, the report says that “demand response resource acquisitions” could help make up the gap in electricity and help with peak demand. On page 68, the report says, “NWPCC estimates that demand response programs and policies could reduce summer loads by 3,721 MW and winter loads by 2,761 MW.” NWPCC does not indicate that this is likely or even possible in the current policy environment. There would need to be significant changes in rate structures and other policies to make this happen and it would take several years to reach these theoretical goals. The report should acknowledge that these goals are aggressive and unlikely. Indeed, the 2022 NWEC study (Energy Strategies) did not include demand response in its analysis due to the theoretical nature of the effectiveness of demand response.

On page 69, the report notes that destroying the dams would increase the cost of electricity across the region. It notes, “In order to avoid these rate increases most, if not all, of the funding for these replacement resources will need to come from the federal government supported by the nation’s taxpayers, in contrast to utility ratepayers.”

There are two big problems with this mindset.

First, the funding to pay for these increases still has to be paid by American taxpayers and that funding goes to pay for the destruction of the dams rather than other priorities like healthcare funding, national security, or tax reductions. This is still a cost and has an impact on the well-being of the people of the country.

Second, the notion that having federal taxpayers pay for something absolves us of paying at the state or local level, is silly. Pretending that people in Alabama are “paying” for our overpriced electricity ignores that, by the same logic, we are “paying” for projects in Alabama and elsewhere. It leads to a perverse mindset where Washington state residents are trying to milk the rest of the country to pay more for our projects than we pay for theirs. This is a corrosive, misleading, and predatory approach to policy.

The reference to federal taxpayers should be removed since that doesn’t eliminate the cost but simply imposes costs on other Americans.

Sources

On page 66, the report notes that “The three main studies that define LSRD replacement portfolios are the 2020 CRSO EIS, the 2018 Northwest Energy Coalition (NWEC) Lower Snake River Dams Replacement Study and the 2022 Lower Snake River Dam Replacement Update (Energy Strategies).” You should note that both the NWEC study and the “Energy Strategies” study were paid for by the NWEC, which is openly supporting the destruction of the Snake River Dams. In its slide deck, the “Energy Strategies” study says “PREPARED FOR THE NW ENERGY COALITION.” The report should note that these studies are both paid for by NWEC and that the NWEC is openly pushing for the destruction of the Snake River dams.

The only independent study on the impacts to energy is the CRSO EIS. That should be made clear.

Columbia River DART, Adult Passage Annual Counts, Lower Granite, https://www.cbr.washington.edu/dart/wrapper?type=php&fname=adultannual_1657559814_505.php

Columbia River DART, Adult Passage Annual Counts, Ice Harbor, https://www.cbr.washington.edu/dart/wrapper?type=php&fname=adultannual_1657559746_825.php

Welch, D.W., A.D. Porter, E.L. Rechisky. (2021). A synthesis of the coast-wide decline in survival of West Coast Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha, Salmonidae). Fish and Fisheries, 22: 194– 211. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12514.

Michael Kinter-Meyer et al., “Electric Vehicles at Scale – Phase I Analysis: High EV Adoption Impacts on the Western U.S. Power Grid,” p. vi, https://www.wecc.org/Administrative/Kitner-Meyer EV-AT-SCALE_1_IMPACTS_final_amended.pdf