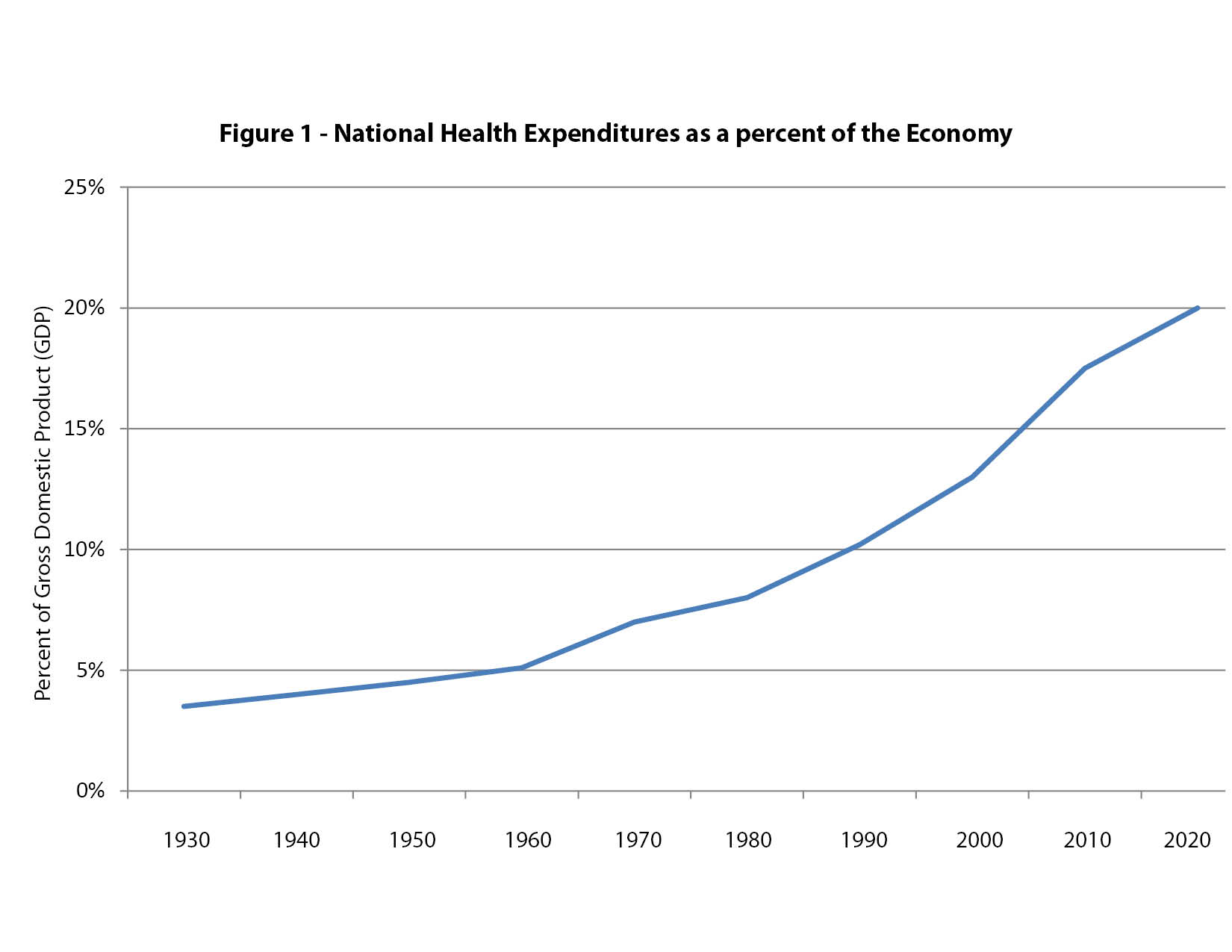

- In 2013, total spending on U.S. health care was $2.9 trillion or 17.4 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP), the highest in the world. Without significant reform, spending is projected to reach 20 percent of GDP by 2021.

- There is no real free-market in health care today. Employees can only take insurance plans offered by their employers. Low-income people and the elderly are forced into government insurance programs without free-market choices.

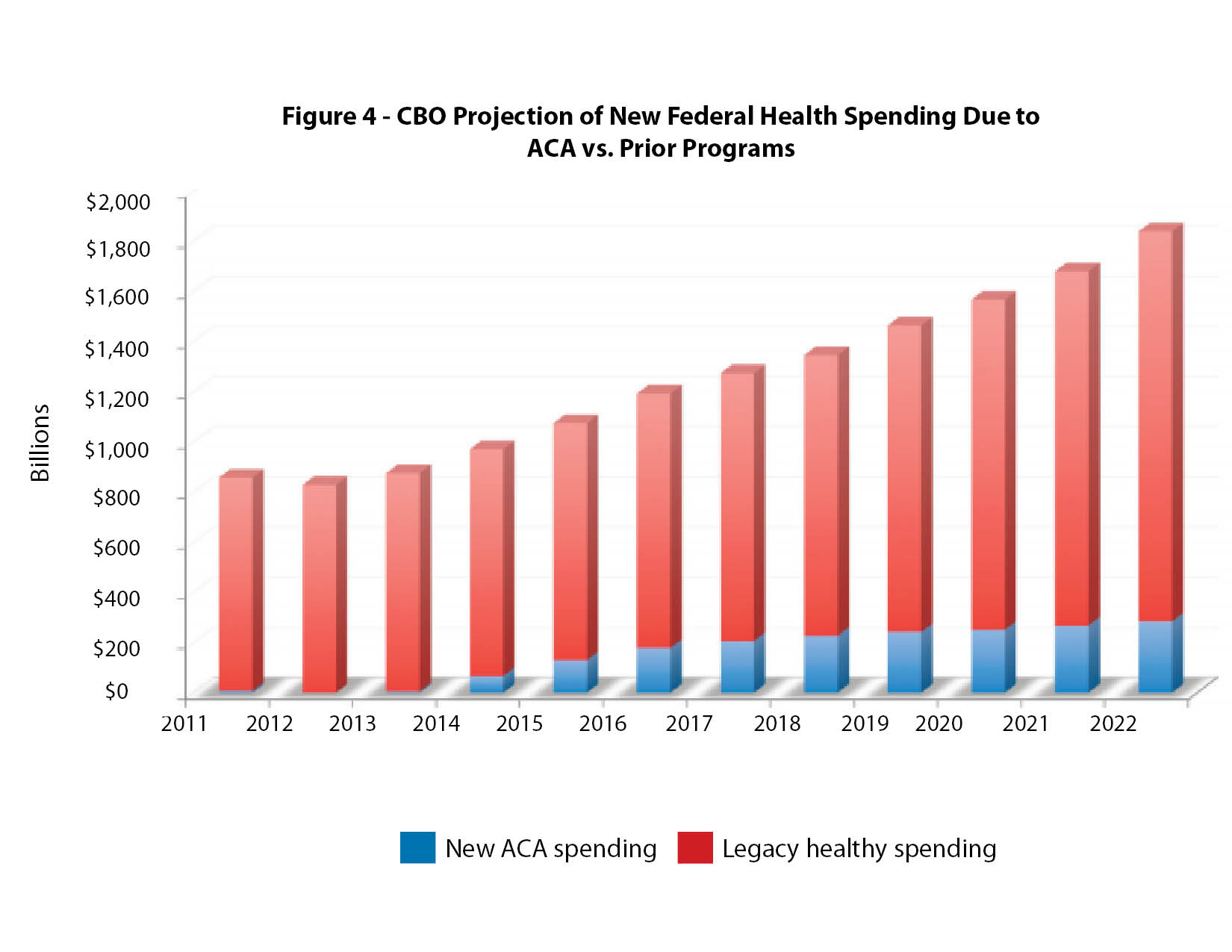

- Repealing or reforming the Affordable Care Act (ACA or Obamacare) without changes to Medicare and the Medicaid entitlement would not solve the health care financial crisis. The ACA is only a small part of overall government spending on health care.

- Meaningful reform and achieving lower costs requires patients to be in charge of their own health care through:

- Provider transparency

- Changes in the tax code and less dependence on employer-sponsored coverage

- Insurance reform

- Eliminating mandates

- Reform of Medicare, Medicaid and ACA programs

- Use of subsidized high-risk pools to deal with pre-existing conditions

- Tort reform

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA or Obamacare), became law in 2010. It was designed to slow rapidly rising health care costs and to provide affordable health insurance to every legal resident in the United States.

Although the law has never enjoyed popular support, polls show that the majority of Americans want the law reformed and improved rather than repealed. The ACA contains certain provisions that people find attractive, such as requiring insurance companies to sell health insurance to anyone regardless of pre-existing medical conditions. Politically, total repeal appears unlikely. From a practical standpoint, would reforming the ACA be significant enough in light of the other government programs (Medicare and Medicaid) and employer spending on health care? Would changes to the ACA be enough to improve the health care financial crisis and expand affordable insurance coverage to all citizens?

To understand the health care crisis in the U.S. and to consider specific solutions, we must first review the origins and impact of the existing insurance programs and how they relate to each other.

History

In 2013, total spending on health care in the U.S. was $2.9 trillion or 17.4 percent of our gross domestic product (GDP). Without significant reform, spending is projected to reach 20 percent of GDP by 2021, as shown in figure 1.

Health care spending was fairly constant, between three and five percent of GDP, from 1930 to 1965. Health care costs exploded after the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965.

Employer-paid health insurance is common only in the United States and dates back to 1943. During World War II, the federal government instituted wage and price controls, but it did allow employers to offer tax-free benefits, including health insurance for employees. After the war, the wage and price controls were repealed, but the concept of tax-free employer-paid health insurance has continued to the present time.

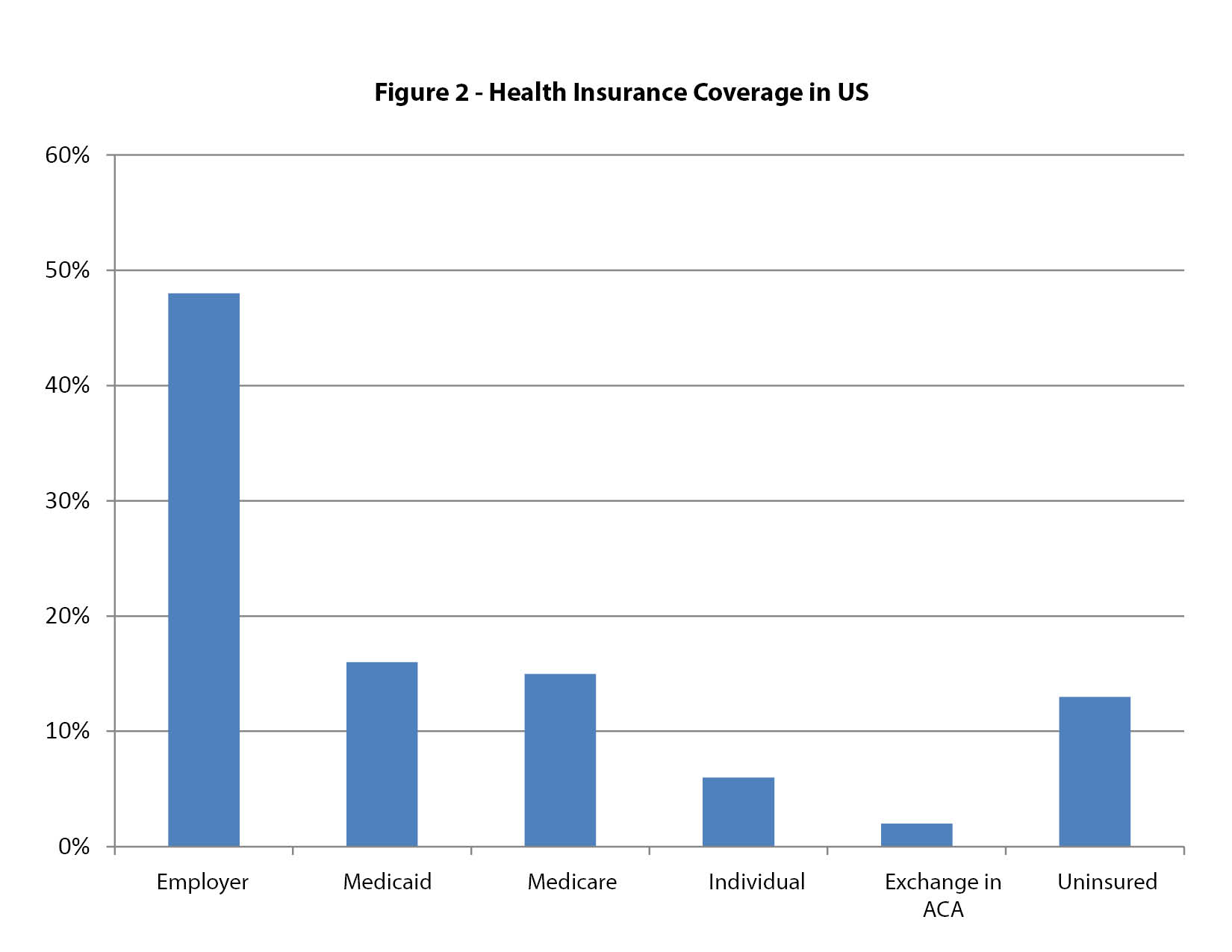

The government became seriously involved in paying for health care in 1965 with the passage of Medicare and Medicaid. The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 expanded the role of government in paying for health care. Employers and government now pay for health insurance for the vast majority of people living in the U.S. as shown in figure 2. Due to the heavy involvement of tax policy and government regulation in health insurance, there really is no free-market in health care today. Employees can only choose from the limited number of insurance plans, often only one, offered by their employers. People with limited incomes and people 65 years of age and older are required to enroll in government insurance plans without free-market choices.

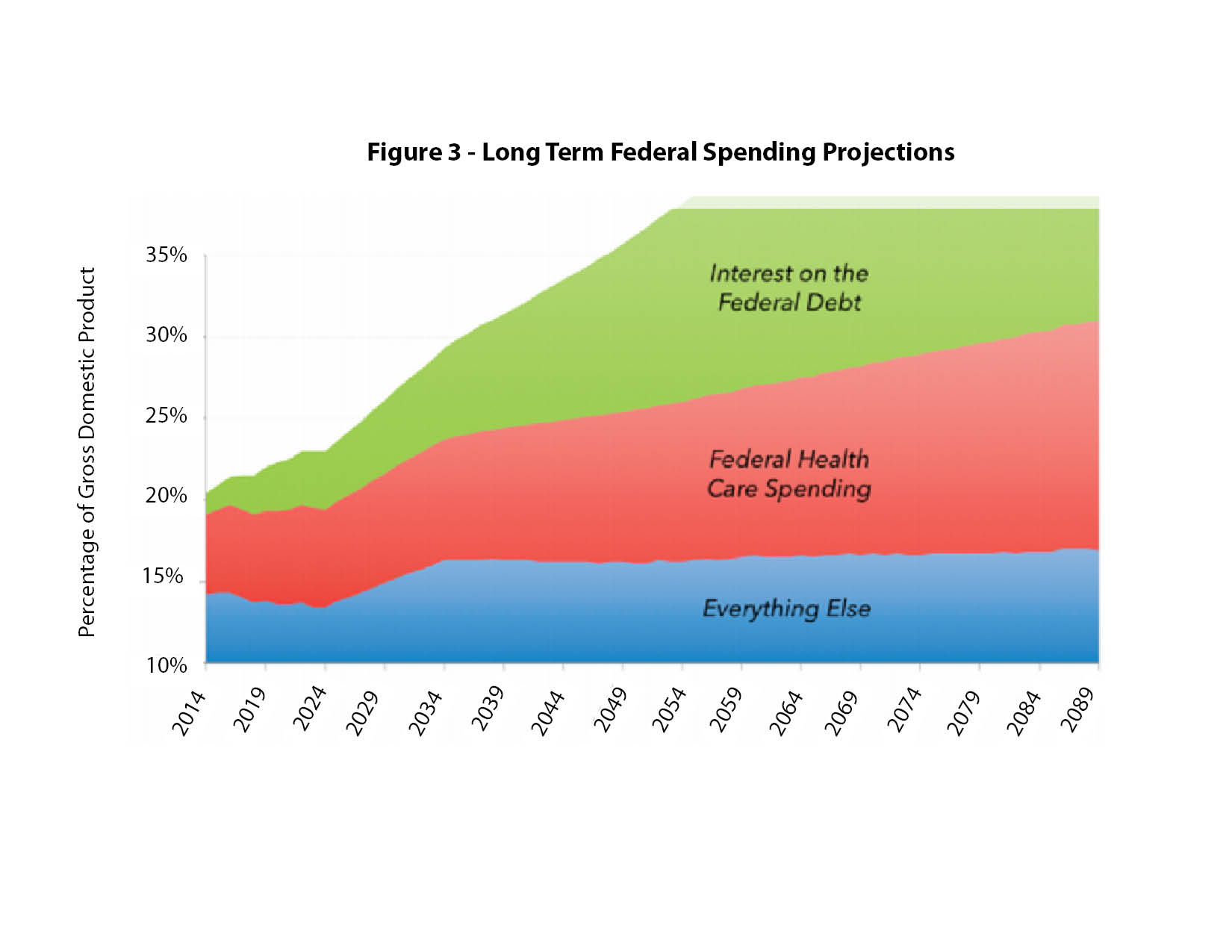

Within negotiated contract limits, employers have the option of dropping employee health benefits. The government cannot drop enrollee coverage unless Congress or state legislatures change entitlement laws. As a result, the cost projection for government spending on health care is rising to alarming levels, as illustrated in figure 3.

Health care spending is the main cause of the relentless increase in overall federal spending and health care entitlement spending is consuming an ever-larger share of the annual federal budget.

Government spending on health care

The chart shows that repealing or reforming the ACA without changes to Medicare and Medicaid would not solve the health care financial crisis. The increasing cost of the ACA is certainly adding to the burden of public spending, but even future ACA spending increases will make up only a small part of overall government spending on health care.

Overview of the Medicare program

The federal Medicare program began in 1965 as health insurance for anyone age 65 and above. It is one of the largest social welfare programs in the world and functions essentially as a single-payer system. Workers pay a Medicare tax during their working years and then must enroll in government-provided health care after reaching the age of 65. The average worker uses three times as much health care as they had paid for during their working years. In 2013, 54 million people nationally and over one million people in Washington state were enrolled in Medicare. Total national spending on Medicare was nearly $512 billion in 2013.

Like Social Security, Medicare was intended to work as a pay-as-you-go system, where current benefits are funded by current taxes. With the decreasing number of workers in the U.S. in future generations, compared to the total population, and with the massive number of baby-boomers approaching retirement age, this pay-as-you-go entitlement system is a fiscal catastrophe waiting to happen. Medicare pays medical providers about 70 percent of what private insurance pays. A growing number of doctors say they are unable to see new Medicare patients and still pay their overhead and expenses. This trend is increasingly limiting access to health care services for our seniors.

If Medicare is to continue in its present form, policymakers must take one or more of three possible steps: benefits will need to be decreased, payroll taxes will need to be increased or seniors will need to pay more out of pocket. A fourth option would be to use general taxes to cover more of Medicare’s yearly deficit. From an economic standpoint, none of these steps would predictably rein in the costs or decrease the demand for health care on the part of Medicare beneficiaries.

Overview of the Medicaid program

The traditional Medicaid entitlement program, which was enacted in 1965 as part of the Medicare bill, provides both federal and state health care funding for poor children and their families, as well as for disabled individuals. It also provides long-term care. As part of the ACA, states are allowed to expand their Medicaid programs to include any low-income adult.

As of 2014, the Medicaid program covered 68 million individuals nationally and 1.7 million people in Washington state. It is the largest entitlement program in the world and functions as a single-payer, government-controlled health insurance plan.

Although the expanded Medicaid created under the ACA is largely funded by the federal government, approximately half of the traditional Medicaid is funded by state taxpayers. Medicaid entitlement expenditures are the fastest growing budget items for virtually all states and the program’s cost ranks number two behind funding for K-12 public education in Washington state.

Doctor reimbursements in the program are 40 to 50 percent of what private insurance pays. Like Medicare, an increasing number of physicians are withdrawing from the program, saying the small government payments they receive are not enough to maintain their practices, which in turn sharply limits access to health care services for enrollees.

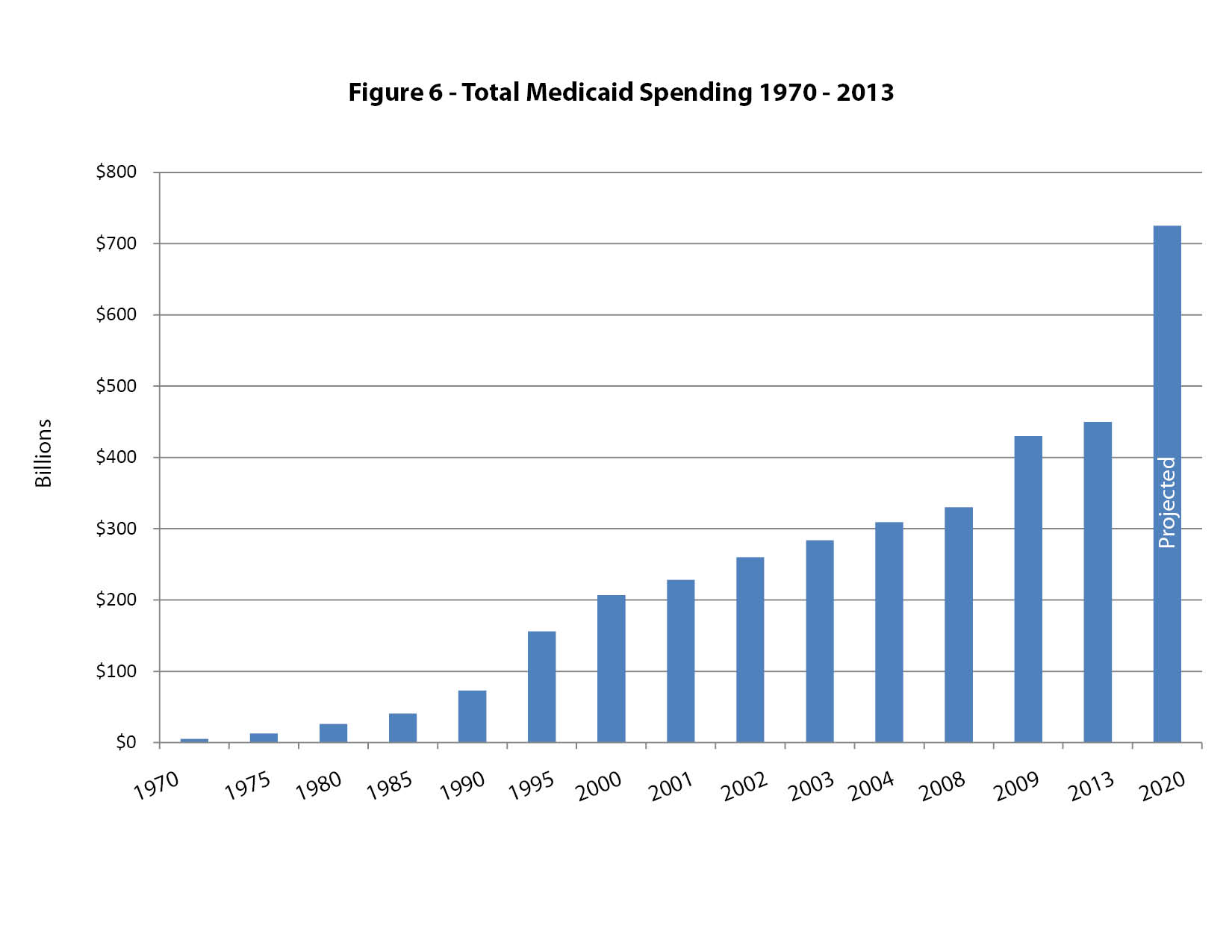

The cost of the Medicaid entitlement was $1 billion the first year, and it had exploded to $450 billion by 2013.

At the present rate of growth, and even without considering the expansion created by the ACA, Medicaid entitlement costs will reach $725 billion a year by 2020.

Medicaid has resulted in a number of harmful consequences. It discourages work and job improvement for low-paid employees, since with increasing income workers stand to lose their Medicaid benefits. It also encourages low-wage employers to not offer health benefits, leaving it to government to cover these costs instead. It discourages private insurance companies from offering long-term nursing-home policies, and as a result this private market shrinks every year. Lastly, a Harvard University study of the Oregon Medicaid program concluded that clinical outcomes for patients enrolled in Medicaid were no better than a similar group of people who did not have health insurance.

State lawmakers are caught in a vicious cycle in which the more money they spend on Medicaid, the more money they receive from the federal government, even though the cost is born by their own constituents, who are also federal taxpayers. It is no surprise that the Medicaid entitlement is the largest, and fastest growing, budget item for almost all states in the country.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA or Obamacare)

The ACA was passed into law with only Democratic votes in 2010. The main goals of the law were to slow the rise in health care costs and to decrease the number of uninsured in the U.S. The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated the cost of the ACA would be approximately $1 trillion for the first ten years.

Taxes to pay for the program began in 2010, but benefits did not start until 2014. In other words, the original budget was based on 10 years of income to pay for the program, but only six years of payouts for benefits. There are no CBO estimates for the ACA’s costs in its second 10 years, but independent analysis shows the potential cost could be over $2 trillion, adding a substantial financial burden on the U.S. yearly budget deficit and the national debt.

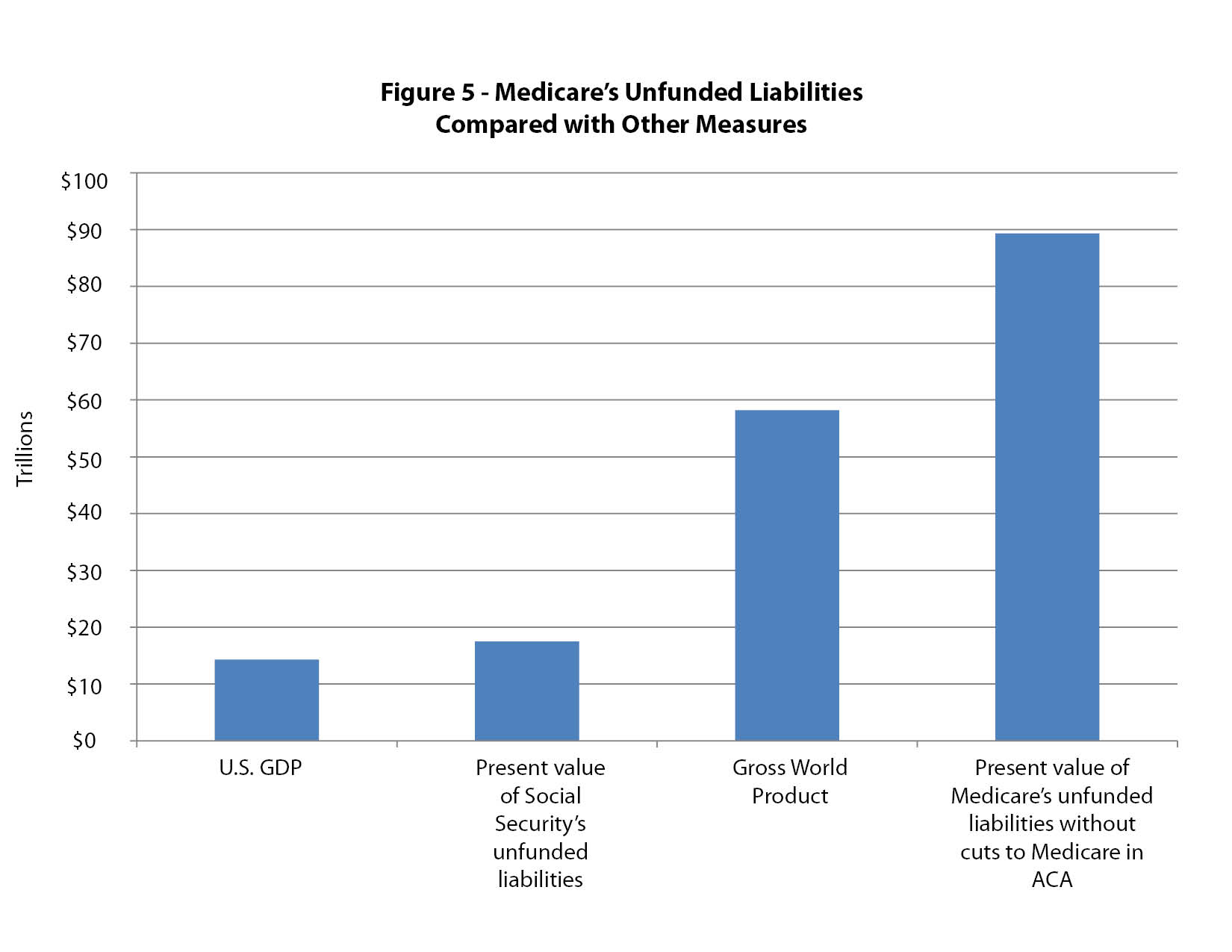

The funding for the ACA comes from two main sources. Almost one half of the $1 trillion in spending in the first 10 years will come from new or expanded taxes and the other one half will come from large cuts to the Medicare program. These Medicare cuts are essentially an accounting function because they will simply transfer funding from an existing government health care program to the new health care plans in the ACA.

After removing $40 billion to $50 billion for administrative costs, the balance of the $1 trillion will essentially fund two programs – a large expansion of Medicaid entitlements ($450 billion) paid for by the federal government, and taxpayer subsidies for people to purchase health insurance in newly-created state and federal health insurance exchanges ($450-500 billion). These numbers are simply guesses, because no one knows how many people will be eligible for, and will claim, the new entitlements. Historically, government estimates of the cost of federal entitlement programs have been universally incorrect and much too low.

State taxpayers are also federal taxpayers. Consequently, as states such as Washington expand their Medicaid programs under the ACA, their state taxpayers will ultimately be responsible for the entire cost of that expansion.

U.S. health care spending compared to other countries

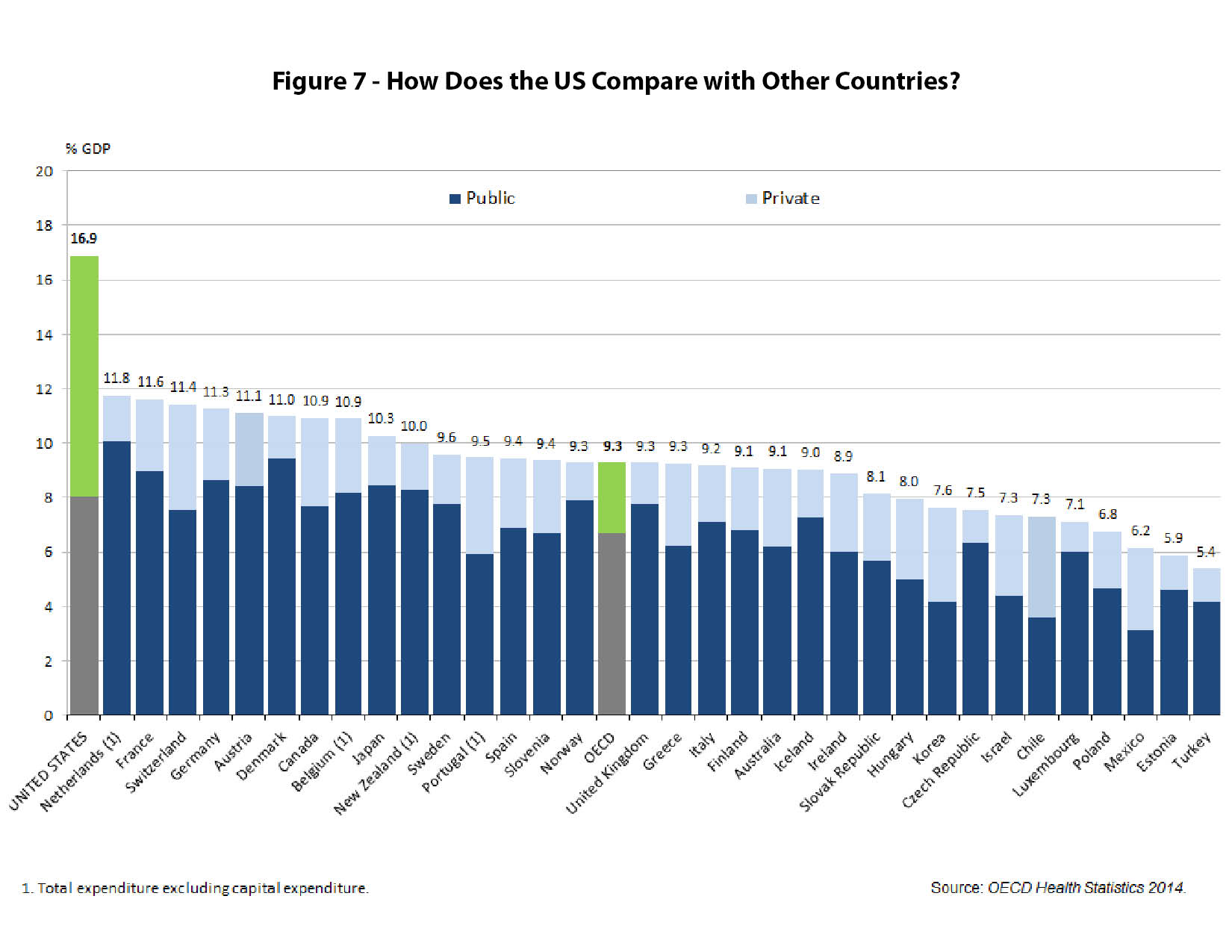

Other countries spend far less than the U.S. on health care, as shown in the comparison chart in figure 7.

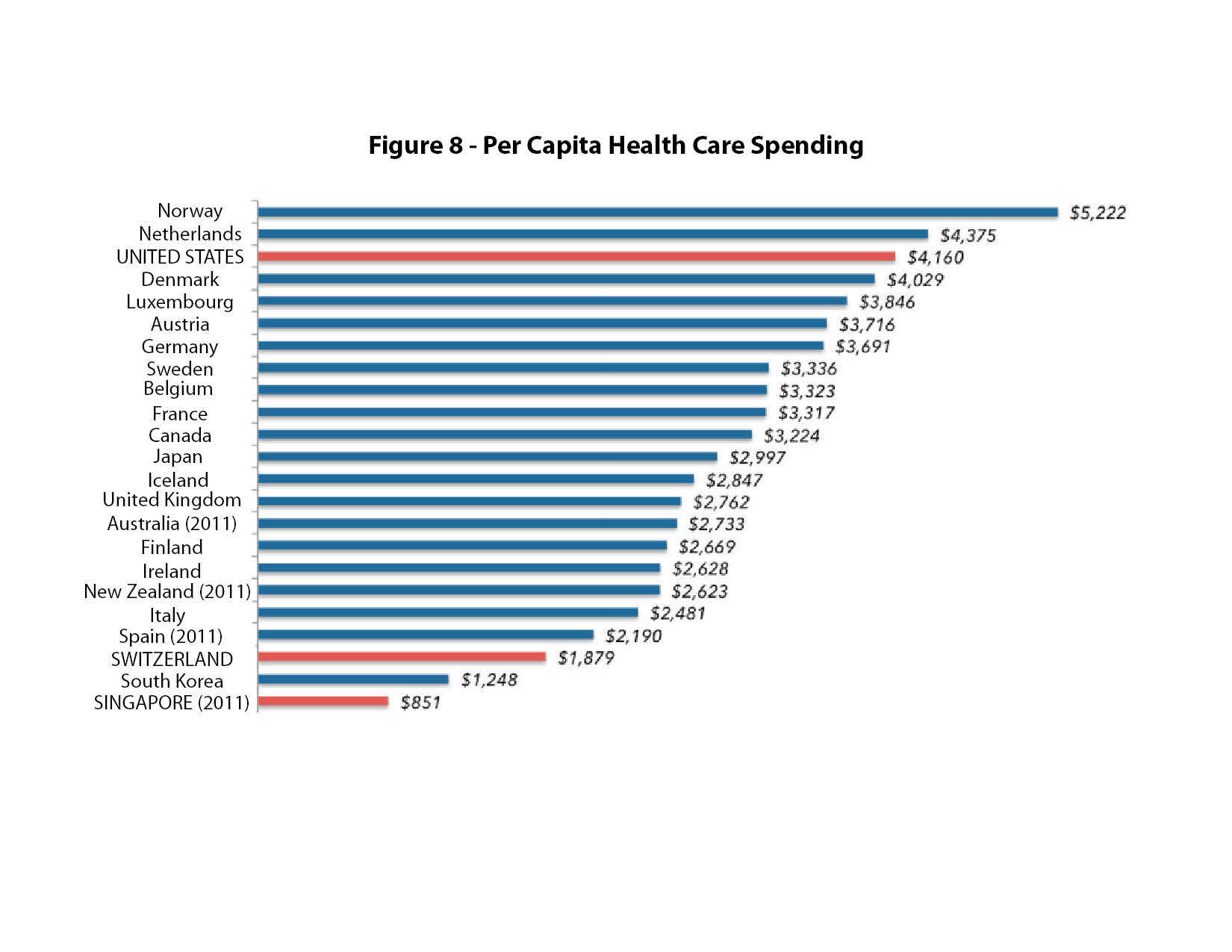

Government spending on health care per person in many countries is actually less than total government spending per person in the U.S., as shown in figure 8.

Nearly all other industrialized countries have some form of socialized medicine.

Canada

Canada’s health care system is a true single-payer system. It is financed with 50 percent federal money and 50 percent provincial taxpayer funds, although the poorer provinces contribute a lower percentage. Health care revenue comes from both income and sales taxes, with up to 20 percent of the budget provided by a payroll tax on workers. The income tax rate reaches nearly 50 percent in Canada.

Every Canadian citizen has government-controlled health insurance with no co-pays for primary care and essentially free choice of physicians. Provider fees are set by the government. Although on paper all Canadians have health insurance, gaining access to health care service is a problem for many Canadians. Wait times for diagnostic and specialty care range from 14 to 40 weeks. The U.S serves as Canada’s medical safety valve, providing a nearby, though often costly alternative for those unable or unwilling to wait for care.

Great Britain

Great Britain established a comprehensive government health care system in 1948. It essentially provides cradle-to-grave coverage for every citizen. The national system provides open access to primary care, although the general practitioner may not be of the patient’s choosing. There are very modest co-pays and basically no hospital charges. The entitlement is financed through general taxes as well as a small payroll tax on workers. About ten percent of the population has private insurance and many physicians combine government entitlement work with private practice.

Like many nationalized health care systems, it is difficult for people in need of care to turn their legal entitlement into access to actual health care service. Most rationing under these systems takes the form of long waiting lists. Wait times for diagnostic and specialty care in Britain became so long that the government ruled in 2010 no one should have to wait more than 18 weeks (four-and-a-half months) for treatment. Medical and administrative inefficiencies are rampant, and chronic shortages, with resulting rationing, are commonplace. Some British families have filed lawsuits claiming medical neglect of elderly parents or grandparents who died waiting to receive care.

Switzerland

Switzerland uses a model of government “managed competition” with an individual mandate to purchase health insurance. It is not employer-based and relies on “private” insurers who must honor guaranteed issue rules (they must sell to anyone regardless of pre-existing conditions) and community rating (all people except for smokers are placed in the same risk pool).

Individuals pay approximately 30 percent of their health care expenses out-of-pocket and the government subsidizes nearly one third of the cost of covering all Swiss citizens.

Insurance companies set payments to doctors in a cartel fashion and compete on policy price and benefits. Basic benefit packages are determined by the government. Because of organized special interests, the political influence of the government is constantly expanding the mandatory basic benefit package, putting upward pressure on insurance prices.

Because employers are not involved, the Swiss are well informed about the full cost of their health care. This has led to a greater degree of informed consumerism in health care than in other countries. Yet because the list of government-mandated benefits in any insurance plan continues to grow, the Swiss are paying more and finding fewer options for health insurance.

Japan

Japan socialized its health delivery system in 1961, when the country required everyone to join a health insurance plan directed by the government. The entire system is essentially a pay-as-you-go plan. Retirees, self-employed and unemployed are covered by the National Health Insurance Plan (NHIP), and workers are enrolled in one of the various employee plans. The NHIP is funded by the government and the employee plans are equally funded by employers and workers. Monthly premiums differ based on salary.

Since 1995, when extrapolation of spending tends revealed that by year 2025 Japan would be consuming 50 percent of its GDP for medical care, the Japanese system has undergone gradual reform. Seniors must now pay an increasing fixed premium and worker co-pays have gone from 10 percent to 20 percent. Likewise, physician reimbursement has been adjusted downward and continues to be re-evaluated.

Fundamental problem in other countries

The demand for health care far outstrips the money budgeted for it in all other countries. The results of this supply/demand mismatch are chronic shortages followed by rationing of health care. The rationing can take many forms – from long waits, to not providing the elderly with certain procedures, to allowing individuals with political influence to “jump the queue” and receive priority attention from providers.

Virtually every country faces the demographic problem of an aging population and a decreasing work-force to pay taxes for their health care.

Policy solutions

The U.S. government’s health insurance programs (Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Administration and the ACA) and the employer-model of providing health insurance were established by federal law. Only Congress can change or repeal these laws. State legislatures have very limited ability to significantly reform the current health care system. Consequently, most of the solutions depend on the federal government enacting changes.

The free market

Buying coverage and using health care services is an economic activity. Because of the close relationship between patients and providers, it is the most personal of all economic endeavors. So why are costs increasing and quality being questioned in health care and not other economic areas? For example, food production has grown exponentially with lower costs. The price, choice and quality of clothing has improved and the availability of other goods and services broaden every day. Prices for electronic goods and telecommunication devices drop steadily, while quality and performance continually increase.

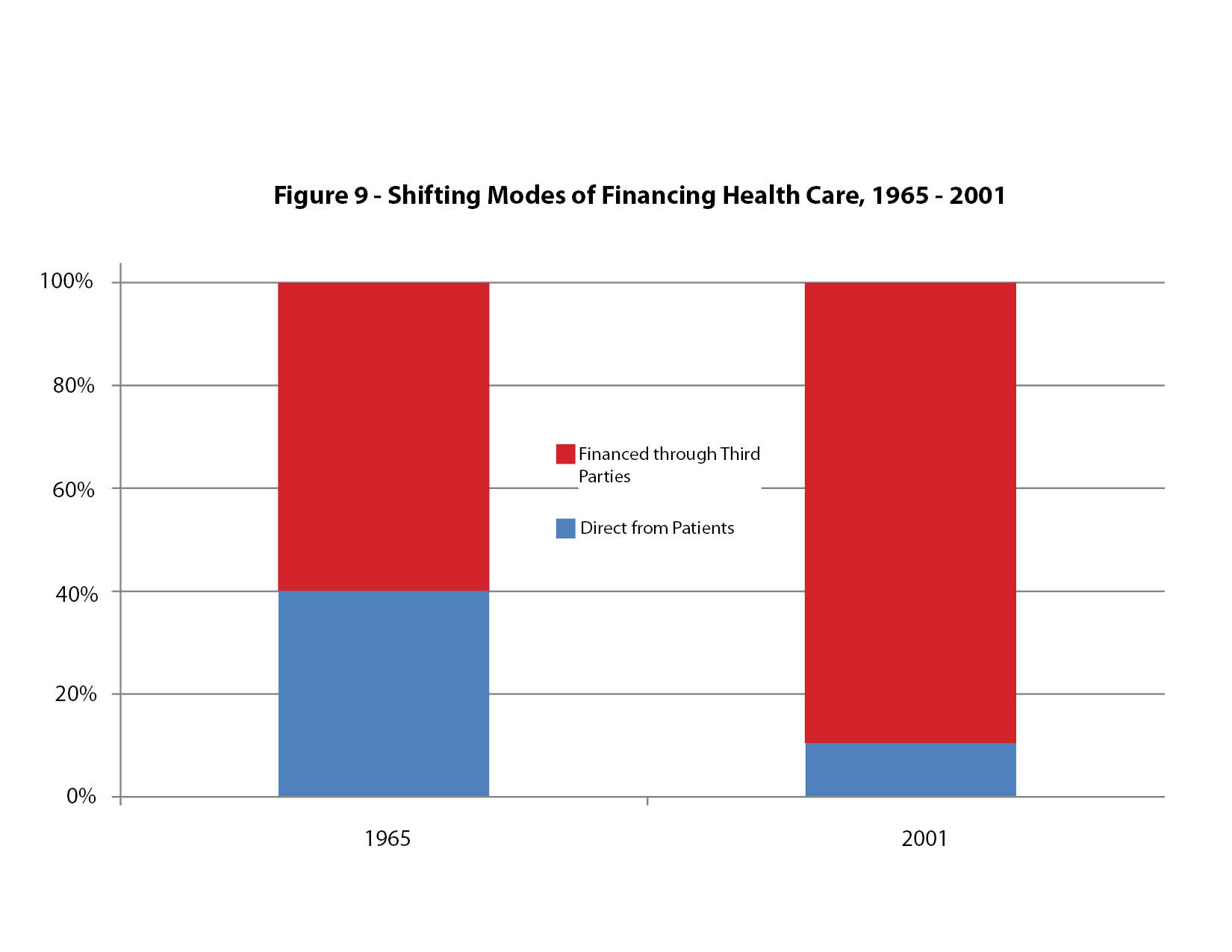

The basic difference between health care and these other economic activities is the fact that consumers use their own dollars to purchase these other goods and services. Almost 90 percent of health care in the U.S. has historically been purchased for the consumer by a third party.

Some argue that health care is so essential and often needed so quickly that normal consumer choices are not possible. How does a person make an informed choice while experiencing a heart attack or stroke or other major incident? It turns out that almost 85 percent of health care delivery in the U.S. is planned and routine while only about 15 percent is of an emergency nature. For most medical care, the patient has time to become a knowledgeable consumer. In a free and open insurance market, competitive policies for emergency medical coverage would be chosen by individuals long before an emergency arises. Likewise, community standards for free emergency medical care could be established, just as we have with fire fighting, policing and 911 disaster services.

In a truly free market, the patient as a consumer would benefit immediately from the effects of competition and improving technology. The motivator for cost awareness in health care would be eliminating third-party payers and allowing patients to control their own health care dollars. This would increase competition, increase innovation at lower costs, insure quality and improve access. It is arrogant for opponents of consumer empowerment to argue that people cannot become wise consumers of health care.

Reforming or repealing the ACA is not enough. Major reforms to the federal Medicare and Medicaid entitlement programs and to the employer-subsidy model must be made as well.

Price transparency in health care

For patients to become informed consumers of health care, they must first know the true price of the services they receive. Doctors and hospitals should publish their prices and compete, not only on quality, but also on retail prices. When people spend their own money, they become smart shoppers. This would be true of health care too.

This shift would be a major change for providers and patients, but in other areas of life, Americans have a long history of consumerism. Through consumer-reports, second opinions, the internet and other tools, most patients would learn to make wise health care decisions.

Change the tax code to reduce dependence on employer-provided coverage

Employer-paid health insurance is a firmly established tradition in the U.S. because the tax code rewards employers, but not individuals or families, in buying health insurance. This has caused a huge distortion in health care spending, because most employers are ill-suited to make sensitive choices about health coverage for their employees. Everyone wants a healthy workforce, yet employers don’t pay for other necessities of a healthy life, such as food, shelter and clothing.

To allow individuals to control their own health care dollars, the tax code should be changed to let all individuals take the same tax deduction for health insurance costs that employers have had for 70 years. A change in mind-set is also needed to eliminate the idea that employers should provide employee health coverage. Employer-paid health insurance is an example of tax policy dictating health care policy.

Similar proposals include federal law providing a level of insurance premium support or earned tax credit. The details of the various proposals differ, but the core concept is based on patients as consumers controlling their own health care dollars.

Insurance regulatory reform

Policymakers should change how they view health insurance. Instead of government-mandated “insurance” and entitlement programs that attempt to cover every possible health-related activity, health coverage needs to work like other forms of indemnity insurance used to mitigate risk, such as car, homeowners and life insurance.

Just as it makes little sense to use insurance to pay for gas or to mow the lawn, policymakers need to get away from the idea that health insurance should cover all our health-related events. True indemnity insurance should be there for catastrophes and emergencies. Routine day-to-day health services should be paid for out-of-pocket as needed.

We have a good policy mechanism to do this today through the use of health savings accounts (HSAs). These accounts require a person or family to purchase a high-deductible catastrophic policy to cover high-dollar medical expenses, but allow a tax-advantaged savings account to save for day-to-day medical-related purchases. Savings can be accumulated from year to year and the balance in an individual’s personal account can be taken from one job to another.

Eliminate costly mandates

Part of insurance reform would be to eliminate provider and benefit mandates imposed by government in insurance plans. Mandates set by government officials and policymakers now restrict patient choice in the purchase of health insurance. Washington state currently imposes 57 benefit and provider mandates. These go far beyond the 10 mandates required in the federal ACA.

Supporters of mandates say no one can predict a patient’s future needs, so the government should require people by law to buy expensive coverage. That is true, but a catastrophic, high-deductible insurance plan can be designed to cover any future major medical problem. Affordable auto and homeowner insurance policies, except in very unusual circumstances, cover any and all major problems and provide individuals and families with millions of dollars of coverage should the need arise.

Mandates are a classic example of politically powerful interest groups lobbying elected officials to include payment for their services in every insurance policy. Mandates restrict competition, drive up prices and greatly restrict choices for patients.

A reasonable first step would be to allow the interstate purchase of health insurance. Patients would have a huge increase in their choices and the market would become much more competitive. The health coverage that some state governments mandate would still be available, but consumers would make their own decision about whether to buy it.

State exchanges

The ACA includes allowing states to set up health insurance exchanges to distribute federal subsidies to help low-and medium-income people pay for mandated health insurance. Exchanges, both the state agencies and the

federally-run website, are extremely expensive and have been fraught with technical problems. In many cases they much less efficiently duplicate consumer services already provided for free by private markets and brokers.

Subsidies, or premium supports, or even tax credits could be given directly to individuals without the need for a cumbersome government exchange. This would streamline the system, give consumers greater choice, while still providing people needed financial support.

People already receiving subsidies in the ACA exchanges could gradually transition to the reformed individual insurance market. More competition and more choice in this market would lower premium prices and allow people to purchase plans they truly want.

Pre-existing conditions and high-risk pools

One of the most popular features of the ACA is the fact that insurance companies cannot deny coverage to a person because of a pre-existing medical condition. The result is higher insurance costs for everyone, as insurance companies seek to make up for their losses by charging higher prices to their healthy policyholders. Instead of forcing everyone to buy insurance (individual mandate) or forcing everyone to pay higher premiums to cover those with pre-existing conditions, a better plan would be to set up voluntary high-risk pools.

These state-run pools would provide health insurance for those people with high medical costs who find insurance on the private market to be too expensive. Various funding and subsidy mechanisms, such as a small universal premium tax, would be much more efficient and less costly than the current one-size-fits-all system.

Medicare reform

There is virtually complete agreement that the federal Medicare program is not financially sustainable in its present form. The program’s costs are rising, the number of workers paying monthly taxes into the program is proportionately decreasing and the number of elderly recipients is about to dramatically increase as the baby boomer generation approaches age 65.

We now have an entire generation of people who has grown up with Medicare, have paid into it and now expect full medical services in return. We also have people in younger generations who understand the bankrupt nature of the program and do not believe Medicare will still exist when they reach age 65. A fair and workable solution to the Medicare problem must account for both of these generations, as well as provide reliable health coverage for future generations. As a country, we have a moral obligation to seniors already enrolled in the program and to those approaching retirement age.

A simple first step to Medicare reform would be to gradually raise the age of eligibility. When the program started in 1965, the average life expectancy in the U.S. was 67 years for men and 74 years for women. Average life expectancy is now up to 76 years for men and 81 years for women, straining an entitlement program that was not designed to provide health services to people for so many years late in life.

As it stands now, there is, understandably, no private insurance market for seniors. Any normal market was crowded out long ago by Medicare. It is virtually impossible to compete with the government, which has monopoly power and an unlimited ability to fix prices and lose money while any potential competitors go out of business.

The private market for the elderly could be resurrected by allowing people to opt out of Medicare voluntarily and allowing these seniors to purchase HSAs and high deductible health plans. Physicians should be allowed to seek partial payments from patients or their insurance companies, which by law, they cannot do now unless they leave the Medicare program entirely.

Future generations should be allowed to continue the individual health insurance they want to keep into retirement. Not surprisingly, younger people as a group are healthier than older people, so as the younger generation saves, their health insurance nest egg would build until they need it in their later years. This is the same strategy that millions of individuals and families use today to prepare for retirement. The federal government informs people that they cannot rely only on Social Security to support them after age 67, and that all working people need to plan for the expected living expenses they will incur later on. The same should be true of Medicare regarding future health care costs.

Medicaid reform

The most important first step to reforming the federal Medicaid program should be to redesign it so it no longer functions as an open-ended entitlement. Welfare reform in the late 1990s was very successful because it placed limits on how many years people could expect support. Medicaid recipients should have a co-pay requirement based on income. Where applicable, enrollees should have a work requirement. Like welfare, Medicaid should be viewed as a transition program to help low-income families achieve self-confidence, economic independence and full self-sufficiency.

It is condescending to believe poor families cannot manage their own health care. Allowing them to control their own health care dollars through subsidized HSAs or a voucher system would financially reward enrollees for leading a healthy lifestyle and making smart personal choices.

Local control of the management and financing of entitlement programs works best. States, rather than the federal government, should be placed in charge of Medicaid. Block grants and waivers from the federal government would allow states to experiment with program design and to budget for Medicaid more efficiently.

The income requirement should be returned to 133 percent of the federal poverty level. Medicaid should not be a subsidized “safety-net” for middle-income people.

Affordable Care Act reform

If adopted, the commonsense reforms listed above would alter the ACA dramatically. In addition, the individual and employer mandates in the ACA should be eliminated. The draconian cuts to Medicare and the onerous new taxes imposed through the ACA should be repealed. Insurance reforms would provide more consumer choices at lower costs which would eliminate much of the need for subsidies. Medicaid reform would make the program a true safety-net for

low-income families who need it, while public policy would encourage and support most people in taking advantage of private-sector competition to prepare for unexpected health care costs.

The ACA imposes a huge, unnecessary regulatory burden on our health care system. These heavy regulations should be repealed or dramatically rolled back to allow a free exchange or prices, coverage options and health services between patients and providers.

Tort reform

Medical outcomes in the U.S. are no worse, and by many measures are much better, than those in other countries. Yet our legal system artificially burdens our health care spending much more than the legal systems other countries have in place.

Regardless of whether or not tort reform is a states-rights issue, cost-cutting legal reforms should be enacted in every state. Meaningful caps on non-economic damages offer the main solution to our current legal award lottery and the drive by trial-level law firms to seek profits.

Conclusion

The passage of the ACA has resulted in a huge increase in government control over our health care system, with a significant reduction in personal freedom and patient choice. Reforming or even repealing the ACA, while an improvement, would still leave the U.S. with a financially unsustainable system.

To control costs, increase choice and maintain or improve quality, patients must be allowed to control their own health care dollars and make their own health care decisions. No third party, whether it is the government or an employer, is more concerned about a person’s health than that person is. Patients, as health care consumers, should be allowed to be informed about, to review the prices of, and to gain access the best health care available in a fair, open and free marketplace.