Download a PDF of this Policy Brief here.

Read this study's two-page Policy Note here.

Key Findings

- The Center for State and Local Government Excellence reports that pension programs for government employees, like maintenance staff, public health workers and librarians are facing unprecedented breakdown.

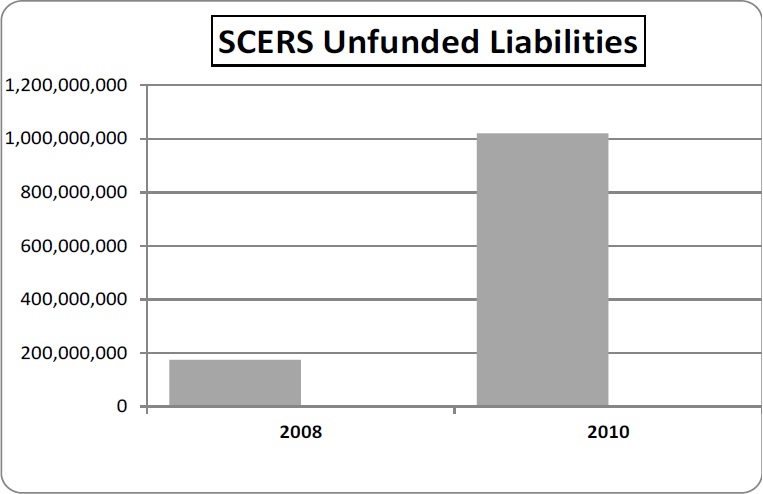

- In 2008, the Seattle pension system had unfunded liabilities of $175 million, which grew to over $1 billion at the start of 2010.

- The volatility and magnitude of this unfunded liability has increased the tension between providing services to current residents while legally fulfilling past pension commitments.

- Benefit increases added by the City in 1998 and 2001 have resulted in much higher monthly payments to retirees. The sharp rise in pension costs is financially impacting the City’s pocketbook as well as those of its employees.

- The Seattle City Council needs to enact comprehensive pension reform that takes a new approach. The goal of reform should be to provide sound retirement income for retirees, but at a lower cost to both Seattle residents and to City employees.

- To enhance fiscal responsibility, several jurisdictions across the country have phased out their traditional defined-benefit plans and established employee-owned defined contribution retirement plans.

- Allowing city workers access to personal defined-contribution accounts would help solve the pension system’s financial problems, while providing a fair and sustainable retirement system for public employees.

Introduction

The City of Seattle pension system is in trouble. A statement by city leaders recognizes significant risks from the rising financial burden of unfunded liabilities and that a new approach is needed. The City pension system, started in 1927, today carries an unfunded liability of nearly $1 billion, a staggering financial burden that must be shouldered by a community of less than 635,000 residents. This study describes Seattle’s pension plan, outlines its defined-benefit structure, assesses it current problems based on official data, reports on how its rising costs are crowding out funding for other public programs and provides practical recommendations for reforms that benefit current public employees, future employees and Seattle taxpayers.

Background – Assessing the Problem

City officials know they face major financial problems with the Seattle City Employees’ Retirement System (SCERS). As with governments across the country, Seattle city council members and the mayor have made pension commitments in the past that are not sustainable. Seattle officials are not alone. The Center for State and Local Government Excellence reports that pension programs for government employees, like maintenance staff, public health workers and librarians, are in the midst of an era of unprecedented breakdown. For officials in many states and municipalities, reform has become an imperative.

To their credit, officials in Seattle have recognized the problem. On November 12, 2010, the Seattle City Council authorized an initiative to develop a sustainable retirement benefit program for the future. The Council’s goal is to design options that continue to provide ample income for retirees, but at a lower cost to both public employees and the people of the City. In its Statement of Legislative Intent, the council members envisioned action on the report’s policy recommendations in 2012, with an implementation effective date of January 1, 2013. The members of the Council’s Budget Committee voted unanimously to pursue this initiative.

Currently, the JDT report remains in draft status and the policy options outlined in the report have not been acted upon by the Seattle City Council.

Interdepartmental Team’s Five Options for a Sustainable Retirement Benefit

A Retirement Benefit Interdepartmental Team (IDT) was created to satisfy the Seattle City Council’s November 2010 directive to explore alternative benefit options the City might offer to new hires. In developing its report, the IDT consulted with pension experts and interested parties in 2011, including the Mayor, the City Council, public employees, labor union executives, the SCERS Board of Administration and taxpayers about the cost and features of the city’s retirement benefits program. The IDT hired consulting actuaries Gabriel, Roeder, Smith and Company to assist them.

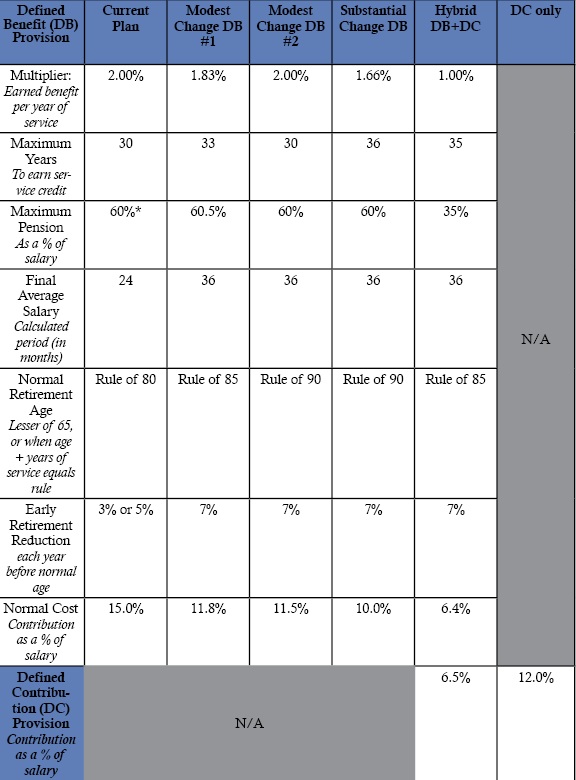

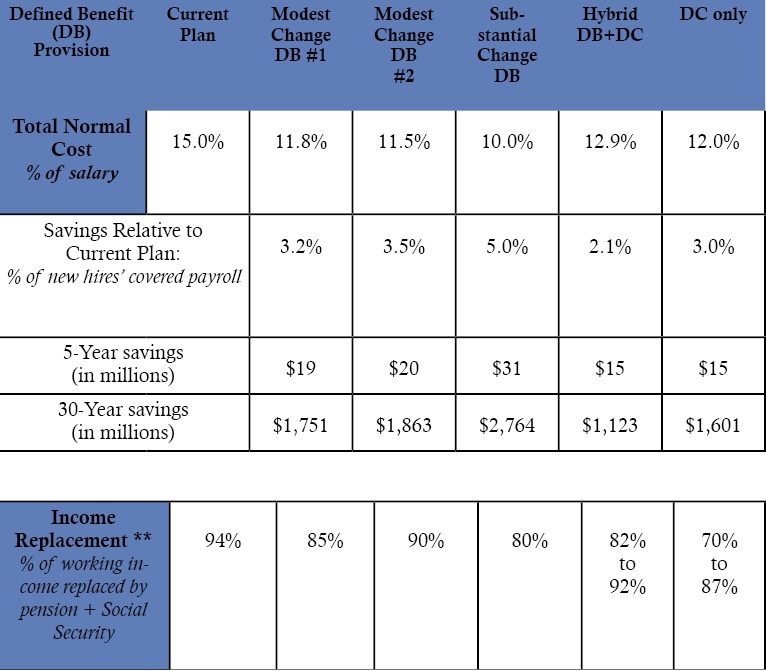

In its thorough, well-researched draft report dated April 9, 2012, the IDT developed five retirement plan options for the City and its employees to consider. They include three plans that would keep the current SCERS defined-benefit structure, but would adjust the benefit multiplier and normal retirement ages, among other provisions.

The fourth plan proposes a hybrid option, similar to the state of Washington’s Public Employee Retirement System 3 plan and the Federal Employees Retirement System. It features a half-sized defined benefit pension coupled with a defined contribution account that together provide similar amounts of retirement income.

The fifth proposed plan is a defined contribution plan, with mandatory contributions from the City and employees, similar to 401(k) plans found in the private sector. All five options would provide, in conjunction with Social Security, enough income to maintain employees’ standard of living in retirement. Adopting one of the new five plans would reduce total pension costs between $15 million and $31 million in the first five years after implementation. The plans would also save the people of Seattle between $1.1 billion and $2.8 billion over 30 years.

It is important to note the projected Defined Contribution Only option’s five-year and 30-year savings would be significantly higher if the assumed employer match was more in line with what is typically paid by private employers. As the Seattle Retirement Interdepartmental Team’s report notes:

“In 2011, a majority (64%) of private employers who offer a DC [Defined Contribution] plan match employee contributions between 3% and 6% of salary, with 3% of salary being the most common policy.”

In coming up with the five options, the Interdepartmental Team and its consulting actuaries assumed a much higher employer contribution of 12%, significantly increasing the cost of the Defined Contribution policy option under this scenario.

The following table shows the five options, including the projected savings that would be realized by the taxpayers of Seattle.

Table 1 – Summary of the Five Plan Options’ Major Features and Normal Cost Savings

Normal cost is the amount needed to finance benefits that are earned today. It does not include any unfunded costs of previously earned benefits.

*May be higher under alternative minimum benefit annuity formula.

**Middle-income earner with 30 years of service who take Social Security at age 65 and has 6.25% to 7.75% average investment returns on the defined contribution account.

These savings on retirement costs would enable the City to spend more tax money on services for the citizens of Seattle, including spending necessary to improve public safety, promote education, enhance public health, relieve traffic congestion and serve other pressing community needs.

Importantly, the IDT report also contains three options City officials may wish to consider for how it implements any change:

- Join the state of Washington’s open PERS 2 and/or PERS 3 plans instead of creating a new plan for Seattle.

- Allow current employees to voluntarily opt into one of the new plan designs in exchange for employee ownership and a lower contribution rate.

- Offer two retirement plan choices, one government-owned and one employee-owned, to new hires.

Pension reform is not easy, but the need for change in Seattle is urgent. Delaying reform only makes the City’s problems larger and more difficult to manage, increasing the financial burden on the public and siphoning money from other parts of the budget.

Seattle Taxpayers Provide a Generous Defined-Benefit Pension Plan

The voters of Seattle authorized SCERS on March 8, 1927. The System began operation on July 1, 1929. The System, known as the Seattle City Employees’ Retirement System (SCERS), is meant to provide retirement income to help maintain the quality of life for its former employees. As of December 31, 2012, SCERS had 9,586 current and terminated employees entitled to, but not yet receiving benefits, and 5,714 retirees and beneficiaries receiving benefits.

The System is a single-employer defined-benefit pension plan, which is intended to provide retirement income to most City employees with the exception of uniformed police and fire personnel. Police and fire employees are covered under a retirement system administered by the state of Washington. Employees of METRO and the King County Health Department, who established membership in SCERS when these organizations were City of Seattle departments, were allowed to continue their SCERS membership.

Seattle is one of only three Washington municipalities which maintain a city-owned pension system, the others being the cities of Tacoma and Spokane. All other municipal governments in the state of Washington place their employees in one of several retirement plans owned and administered by the state of Washington.

The City’s pension is an earned benefit for service, part of the employees’ total compensation package. However, the employees themselves contribute a substantial share of the plan’s costs through a pre-tax payroll deduction, similar to the tax-deferred payments private-sectors workers make to their personal IRA or 401(k) retirement plans.

The main feature of the current SCERS pension benefit is that members earn a generous credit worth 2% of salary for each year of full-time City employment. In this way, a public employee who works for 30 years receives a monthly pension equal to 60% of his or her final average salary.

The pension is guaranteed for life and features a 1.5% automatic annual cost-of-living adjustment (COLA). Employees who work less than 30 years may also retire with a smaller pension, and their benefit may be reduced somewhat for early retirement, depending on their age at retirement.

The plan is designed to work in conjunction with Social Security, so that a member’s total retirement income is the sum of the two benefits. Together, these sources of income are intended to replace between 87% and 109% of working income in retirement. By standard retirement planning measures, this is considered more than adequate to maintain an employees’ standard of living once they leave work.

SCERS Compared to Other Plans – Richer Benefits and Higher Costs

Since about 1978 private sector employers have largely abandoned traditional company-owned, or defined-benefit, pension plans in favor of employee-owned defined-contribution plans, such as 401(k) accounts. Employee-owned plans have no supposed benefit guarantee, but they allow employees to invest their own contributions as they wish, often earning substantial returns.

Tax-deferred employee contributions are often matched by the employer, in portable individual accounts. Most private sector employers with defined-contribution plans provide a maximum match worth between 3% and 6% of salary. Currently the vast majority of retirement funds and their investment earnings are employee-owned.

Public sector employers (including states, cities, counties, and school districts) generally still provide old-style defined-benefit plans, but their benefits are less rich on average than Seattle’s SCERS program.

- Seattle’s 2% benefit multiplier is higher than the 1.85% average for public plans with Social Security. This translates to a 30-year pension that is about 5% higher (60% of salary versus 55%).

- Seattle’s normal retirement ages are also younger than the average for public plans. Normal retirement is the age at which a member may begin benefits without any reduction for early retirement. Many SCERS Seattle employees may retire with full benefits while still in their fifties, young enough to take other, non-City of Seattle jobs while still collecting public retirement benefits. Most public plans have now moved to 60 or 65 as a normal retirement age. The federal government has set the normal retirement age for Social Security at 67.

- Seattle also subsidizes early retirement. Benefits are reduced either 3% or 5% for each year early that a public employee retires. This is well below the factor of about 7% that is needed to ensure that the plan’s costs are not increased when a public employee retires early.

For this richer-than-average benefit, Seattle employees pay about twice as much as the average public sector employee. Seattle’s current employee contribution rate is 10.03% of salary, compared to a national median rate of about 5%.

SCERS and the Financial Burden on Seattle Residents

Pension commitments have become one of the largest categories of unfunded liability for many municipalities providing these benefits. This is true for the City of Seattle as well as other local governments across the country.

As outlined above, SCERS is a government-owned defined-benefit plan, which provides an automatic, formula-driven retirement income to its members, regardless of how successful the City is in collecting the tax money and gaining the investment profits necessary to make these future payments. The difference between projected costs and the assets available to support them is known as the unfunded liability of the plan.

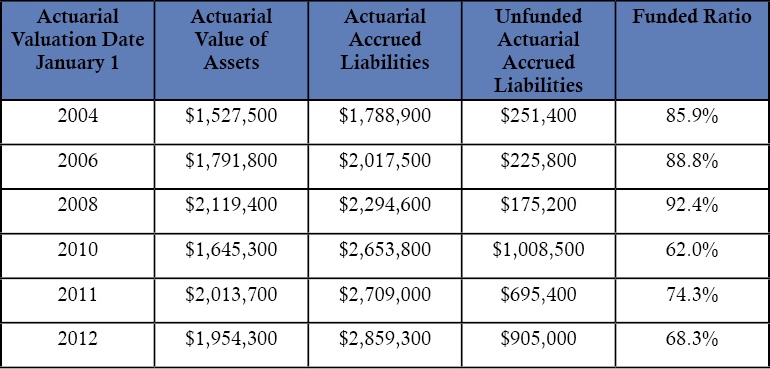

Table 2 shows the System’s unfunded liability as of January 1, 2012, was $905 million, which means the System was only 68.3% funded. While 100% represents full funding, a ratio of 80% or higher that is also stable or improving is considered generally safe by pension experts. A retirement system below 80% funding is at risk of failing to pay retirees the promised level of benefits. The latest actuarial valuation for SCERS was completed as of January 1, 2011.

Table 2 – SCERS Schedule of Funding Progress

December 31, 2012 (In Thousands)

The table also shows that while liabilities have been steadily increasing, the value of assets and the funded status have been volatile. Under the defined-benefit system, the City of Seattle owns its employees’ retirement and assumes 100% of the risk of investing the System’s assets.

At the start of 2008, SCERS had unfunded liabilities of $175 million, which represented a modest 35% of the City’s annual payroll. The plan’s actuary at the time predicted that at the current contribution rate, the City would be able to pay this cost within 16 years, which is under the 30-year time horizon considered safe and appropriate for a government-owned retirement plan.

By the start of 2010 that unfunded liability had grown to just over $1 billion--more than five times larger than before. This liability now represents 174% of Seattle’s payroll. The actuary concluded at the time that the City would not be able to amortize these costs over any period at the current contribution levels.

The volatility and magnitude of this unfunded liability has increased the tension between providing services to current residents while legally fulfilling past pension commitments.

Another important point is that government pensions are not regulated. While there has been a federal law on the books requiring private sector employers to put money into their pension plans on a systematic basis and to pay insurance premiums to the federal pension insurer, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC), the law does not apply to government employers.

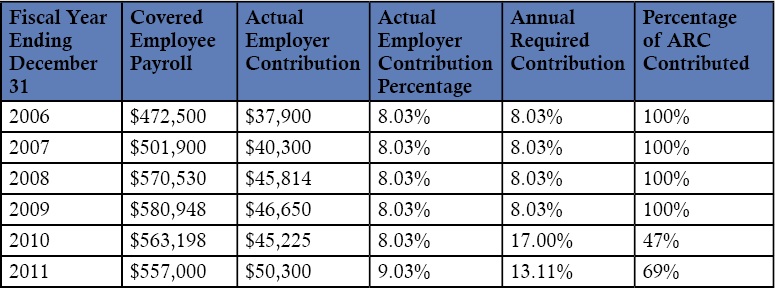

As a result of PBGC’s oversight and rule making, private employers have been required to measure and fund pension obligations as employee service is rendered. This ensures that funds are available when it is time for retired workers to receive benefits. In contrast, very few local government employers, including the city of Seattle, have fully funded pension commitments during the employee’s tenure, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3 – SCERS Schedule of Employer Contributions

December 31, 2012 (In Thousands)

This means government pension commitments made in the past will have to be paid by future generations of taxpayers.

Seattle taxpayers have a critical role to play in understanding how SCERS works and in holding elected officials accountable for the manner in which they administer the System. Understanding Seattle’s pension promises is difficult because pensions are one of those back office functions that are not in the limelight like public safety, education or transportation issues. It is also generally difficult to obtain or understand pension information.

The important questions for the Seattle City Council and, ultimately, Seattle taxpayers, include:

- Should SCERS be reformed for future employees?

- If so, what reform or reforms should be enacted?

- Should the city of Seattle continue to administer SCERS or should it be administered by the state of Washington?

The SCERS Board of Administration and Its Fiduciary Responsibilities

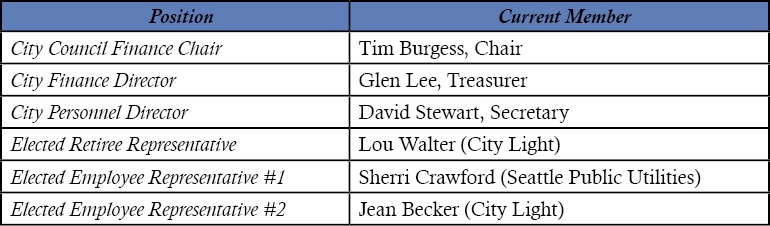

The City, as the plan sponsor, has the ultimate responsibility for SCERS. A seven-member Board of Administration has been delegated the fiduciary responsibility to invest the plan’s money and to pay out benefits to public-sector retirees. The Board is chaired by the City Council member who heads the Council’s Government Performance and Finance Committee. Other members include the City’s Finance and Personnel directors, two elected employee representatives and one elected retiree representative. These six Board members then choose the final seat from the community, someone who is neither a city employee nor a beneficiary of SCERS.

Table 4 – Current SCERS Board of Administration Membership

The Board meets monthly to review and approve retirements and financial transactions and to discuss operational and administrative matters. The Board’s minutes are posted on the SCERS website, which can be found at www.seattlegov/retirementminutes.htm. SCERS staff and outside professional investment consultants advise the Board, and an Investment Advisory Committee, made up of finance and investment professionals, periodically provides advice.

The Seattle City Council Authorizes Pension Benefit Changes

Since its founding in 1929, the city of Seattle has changed its pension policies numerous times, providing a comfortable retirement to several generations of City employees. Authority to change SCERS’ benefits rests with the City Council. It does not require a vote by Seattle taxpayers.

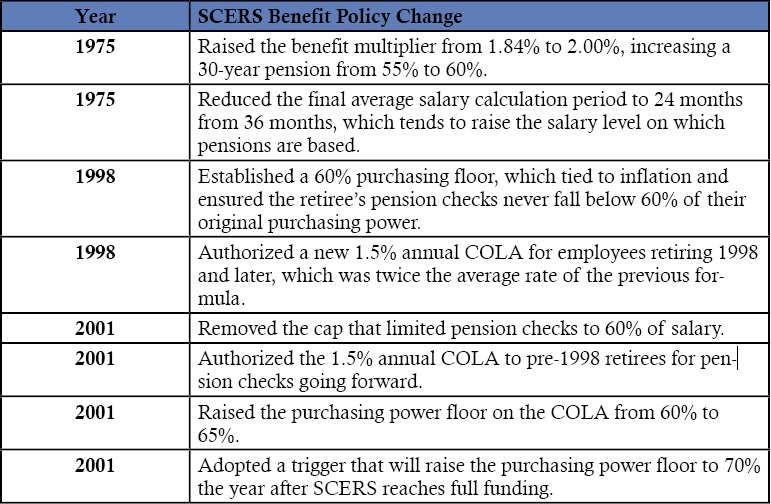

For purposes of understanding how the SCERS benefit has been enriched over time, Table 5 shows the SCERS benefit policy changes that have been authorized after periods of strong investment performance by the Seattle City Council from the early 1970s forward.

Table 5 – SCERS Benefit Policy Changes from the Early 1970s Forward

These policy changes are typical of how public pensions have grown more generous over time. When public employees and retirees demand benefit increases, elected officials tend to grant them after periods of strong investment performance.

SCERS’ Investment Profits Performance and Outlook

The rate of return that a government-owned pension plan earns on its investments is perhaps the single most important determinant of the plan’s financial health, enabling it to pay its promised benefits to retired workers. This is because the majority of a retirement plan’s money typically comes from investment profits, not contributions.

Every pension plan makes an investment return assumption for purposes of setting the plan’s funding requirements. SCERS’ current assumption is that Seattle’s public pension plan will earn 7.75% profit on a 30-year average annual basis.

SCERS has significantly beaten its investment return assumption over the past 30 years, with average annual returns of 8.8% per year. However, the most profitable years occurred in the beginning of that period. Since 2000, the plan’s investments averaged only 3.7% earnings in the last decade, a period that included two major recessions, both of which caused major drops in global stock market valuations.

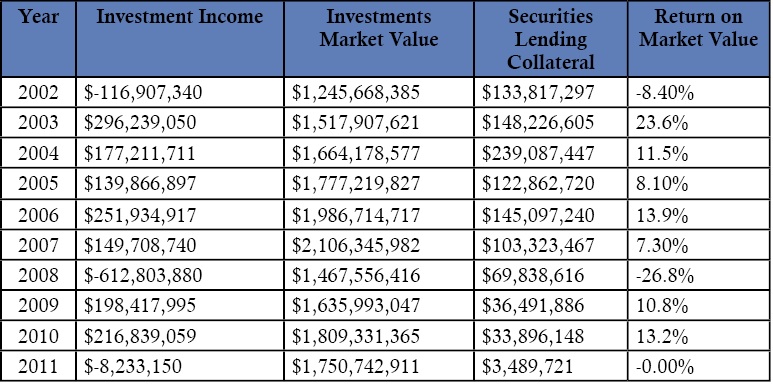

The sharpest decline occurred in 2008 when SCERS took a 26.8% loss. The portfolio has yet to return to its pre-2008 level of $2.1 billion. As of December 31, 2010, SCERS had more than $1.8 billion in assets to pay its pension costs, accumulated from contributions and investment returns in the years before 2008. Figure 6 is a schedule of SCERS investment profits for the ten years ending December 31, 2011.

Figure 6 – Historical SCERS Investment Performance

Ten Years Ending December 31, 2011.

SCERS Employer and Employee Contribution Rates Projected to More Than Double Compared to 1972

SCERS under performance in its investment earnings has required the City Council to steadily increase the other source of funds for the payment of future pension benefits—employee and employer financial contributions.

Employees and the City will soon be paying nearly twice the share of their payroll to the SCERS pension benefit than they did a generation ago. In 1972, contributions to the pension fund totaled 12% of payroll, employee and employer combined. In 2014, combined contributions are projected to approach 24%. Three major factors contributed to this doubling of costs:

- $616 million in investment losses in 2008;

- Benefit increases to the multiplier, the COLA, and other plan features in 1975, 1998 and 2001 resulting in higher monthly payments to retirees; and

- Longer life expectancy, which has added an average of four years in retirement since 1970 and which is projected to add another four years by 2037.

Based on the actuarial valuation of the benefits in effect as of January 1, 2011, the currently scheduled contribution rates are not sufficient to adequately fund promised benefits.

If SCERS meets its investment return targets, then contributions must rise to 23.4% and remain near that level for 30 years to pay off the system’s unfunded liabilities. If investment performance continues to fall short the predicted target rate, then required contributions will continue to rise or benefits will have to be cut. Investment profits will have to be exceptional to avoid further contribution increases.

To put the problem in perspective, after a 26.8% loss, it would take annual profits of over 30% to get back on track within two years; profits over 16% to get back on track in five years, and profits of 12% to get on track in ten years.

There appears to be consensus among investment experts that investment returns will be lower than their historical ranges over the next ten years. SCERS now projects that its portfolio will earn only 7% a year. If this projection turns out to be true over 10 years or more, contribution rates will need to rise an additional 4% of payroll, to 28%.

This benefit and investment history demonstrates a typical pattern in public pension programs. When employees and retirees demand benefit increases, employers tend to grant them after periods of strong investment performance, thinking the more generous monthly payouts will easily be funded by a strong stock market.

These more generous payouts have the effect of permanently increasing costs. Then, when investment performance takes a dip—or, in the case of 2008, a full dive—contribution rate increases from public employers and working employees are the only realistic way to cover the increase in costs.

SCERS Annual Pension Costs are Increasing Faster than Inflation

The City of Seattle’s annual pension costs for the three years ended December 31, 2011 follow:

2009 ....... $46,933,000

2010 ....... $93,924,000

2011 ....... $72,346,000

The SCERS program is not as well funded as it should be. Its funding ratio fell from a healthy 92% at the beginning of 2008 to a risky 68% in 2012. To put this in perspective, retirement experts regard a funding ratio of at least 80% as a prudent level of funding. SCERS’ long-term unfunded liabilities for benefits that Seattle officials have already promised to employees is $905 million as of the January 1, 2012 valuation date.

This represents a 51.55% increase over the combined contribution rate of 16.06%, which was equally shared by employees and the City as recently at 2010. The sharp rise in pension costs is financially impacting the City’s pocketbook as well as those of its employees.

Consumer prices increased by 3.2% in 2011 and by 2.7% during the first eight months of 2012, as measured by the city of Seattle as part of its 2012 budget process. Government salary increases are generally in line with inflation, so the SCERS contribution rate increases are a real hit to employee paychecks, reducing take-home pay.

The next section describes what governments across the country are doing to lower their pension costs for the employer, for employees and for taxpayers.

Pension Policy Changes Are Being Adopted Across the Country

The IDT Study found that state and local pension plans across the country are changing pension policies to lower their costs. Approaches have included reducing benefits, suspending cost-of-living adjustments, increasing contributions, and enacting new limits on “spiking” and “double dipping” practices.

Several states have also recently closed their government-owned defined-benefit plans and replaced them with employee-owned defined-contribution plans for new hires, or have established hybrid plans that mix the features of both.

- 28 states raised employee contributions. This included several states where employees previously contributed nothing to their pension benefit, but must now pay 4% to 5% of their salaries. Some of the contribution increases affected only new employees; others affected all employees.

- 29 states reduced benefits for new employees. The changes included primarily slightly lower benefit multipliers, later normal retirement ages, and steeper reductions for early retirement.

- 14 states reduced benefits for current employees. In some cases these changes were applied to newer, non-vested employees. In others, they were applied to all current employees.

- Four states closed their government-owned defined-benefit plans and created hybrid or employee-owned defined-contribution plans for new employees.

- 18 states either reduced or suspended their cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs). These changes were applied in some cases to current retirees, in others to future retirees, and in others to new employees.

The United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) found similar results when it conducted a study in 2012 of selected state and local government pension plans to identify strategies for lowering costs and improving sustainability in public employee pensions.

The GAO concluded that state and local governments continue to experience the lingering effects of investment losses and budget pressures in the wake of the recent economic downturn.

Although most large state and local government pension plans still maintain substantial assets, sufficient to cover their pension obligations for a decade or more, heightened concerns over the long-term sustainability of the plans has spurred many states and localities to implement a variety of reforms, including reductions in benefits and increases in member contributions.

On the local government front, the GAO study identified the following examples of changes being implemented:

Denver, Colorado. In 2011, the Denver Employees Retirement Plan adopted several benefit reductions for new employees hired on or after July 1, 2011, including:

- Raising the minimum retirement age from 55 to 60;

- Increasing the age and service requirements needed to qualify for an unreduced early retirement; and

- Increasing the period used for calculating final average salary from 3 to 5 years.

Cobb County, Georgia. In 2009, the Cobb County Employees’ Retirement System adopted a hybrid approach for new employees hired on or after January 1, 2010, and for non-vested employees who choose to join the plan. The defined-benefit portion of the plan has a 10-year vesting period with a benefit formula based on 1% of the highest average salary multiplied by years of service. The defined-contribution component of the plan is voluntary, but the County matches half of the member’s contribution up to 2%.

City of Norfolk, Virginia. In 2010, the City adopted changes requiring new City employees hired on or after October 5, 2010, to contribute 5% of compensation. Current members do not make pension contributions.

The Center for State and Local Government Excellence is highlighting two large local governments that have accomplished landmark pension reform:

Phoenix, Arizona. The City of Phoenix Retirement System (COPERS) is a defined-benefit plan. It is established in Phoenix’s charter. Changes to COPERS must be approved by voters, who have approved 25 changes since 1953. In 2013, Phoenix voters passed Proposition 201 (79.5% yes vote), a proposition that increased employee contributions and eligibility requirements for new city workers hired on or after July 1, 2013:

- The member’s contribution rate will be 50% of the annual contribution rate calculated by the Plan’s actuaries with the City paying the other 50%;

- The current Rule of 80 would be replaced with a Rule of 87 (meaning a member’s age and service, when added together, must equal or exceed 87 in order for the member to be able to retire under this option);

- The multiplier factor applied to the member’s years of service to calculate his or her retirement benefits would be changed from a multiplier that decreases over time to a multiplier that increases over time;

- The member would not be eligible to receive a month of service credit for any month in which the member had less than 20 days of service; and

- Any minimum pension obligation is eliminated.

During the same election, Phoenix voters also passed Proposition 202 (77% yes vote), which

- adopts the prudent person rule for investing funds;

- ensures that COPERS remains tax exempt and is administered in accordance with all applicable federal tax laws; and

- allows the City to contribute more than its annual actuarially required contributions.

Atlanta, Georgia. In 2010, Atlanta:

- closed its defined-benefit plan for new employees and replaced it with a hybrid for newly hired workers (small defined-benefit component plus a defined-contribution plan);

- extended the retirement age for new employees by two years; and

- established a cap on the city’s annual contribution to the pension plan.

Current employees will continue in their defined-benefit plan, but they

will have to contribute 5% more of their paycheck.

Beyond the well thought-out strategies outlined in Seattle Interdepartmental Team’s “Options for a Sustainable Retirement Benefit,” the above reform efforts are additional examples of successful efforts being implemented by governments at every level around the country.

Conclusion – Defined-Contribution Plans and a Framework for Reform

In its 2010 Statement of Legislative Intent for developing a sustainable retirement benefit, the Seattle City Council concluded that:

“The contribution rate increases in the 2011-2012 Proposed Budget take a significant step toward amortizing the City’s unfunded pension liabilities, but they do not guarantee success. Significant risks remain that the City’s unfunded retirement liabilities will increase, placing additional burden on City budgets. A new approach is needed.”

The Seattle City Council needs to enact comprehensive pension reform that takes a new approach. The goal of reform should be to provide sound retirement income for retirees, but at a lower cost to both Seattle residents and to City employees. The Seattle Retirement Interdepartmental Team Report lays out viable options, including options for how it would implement any change.

All proposed options would provide, in conjunction with Social Security, ample income to maintain employees’ standard of living in retirement. Any program changes should honor benefits already earned, as accrued benefits are legally protected.

Comprehensive reform needs to accomplish four goals:

- Systematic funding of the Seattle City Employees’ Retirement System (SCERS) unfunded liabilities.

- Adoption of a retirement system for future employees that is affordable, sustainable and secure.

- The reformed retirement component of Seattle’s total compensation package needs to enhance its ability to recruit and retain a talented public-sector workforce.

- Reduces costs for taxpayers and those who depend on city services.

Allowing city workers to have tax-deferred defined-contribution retirement accounts would go a long way toward solving the financial crisis in the City’s pension system, while providing a fair and stable retirement system for employees.

Personal accounts allow employees to supplement their retirement savings during their working career, in addition to employer contributions, and create a secure financial asset that is not subject to changes in City politics. Money placed in an employee’s personal account would be more than just a promise. These would be employee-owned retirement savings that could never be taken away by future mayors and future city councils.

As added security, the accumulated worker and employee contributions, plus all investment earnings, in employee personal accounts would be protected from public bankruptcy proceedings. Unlike public retirees in Detroit, public employees with personal pension accounts would never face the potential loss of their benefits in bankruptcy court.

The importance of properly financing SCERS and providing real long-term retirement security for City employees, the people the community depends on to provide important public services, has never been greater. Reformed pension policies would ensure costs are sustainable and that public employees receive the retirement benefits they have earned, and it would protect taxpayers and strengthen the financial position and credit rating of the City of Seattle.

Download a PDF of this Policy Brief here.

Read this study's two-page Policy Note here.