Members of the State Charter School Commission, created by voters in 2012 as part of Washington’s charter school law, plan to meet Thursday at 10:00 a.m. at South Seattle Community College to consider whether to close the state’s first charter school, First Place Scholars school for homeless children in Seattle.

First Place Scholars opened on September 2, 2014 for the purpose of helping homeless children and at-risk youth gain access to a quality public education. The school combines innovative strategies to provide math and reading instruction to hard-to-teach students with family support services centered on one goal: keeping kids in school.

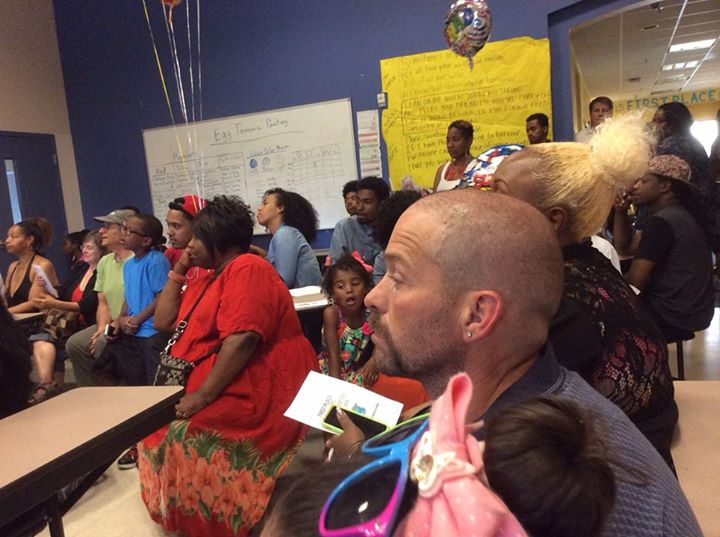

About 80 families have enrolled in First Place. The school integrates support for families in providing a stable and safe environment with classes geared toward helping young people acquire skills and make appropriate choices in life.

The Commission meeting will review hundreds of pages submitted by First Place administrators detailing everything from the school’s plan to provide special education services and hire new teachers to the format of student report cards.

Earlier, the Commission had ruled the school must meet requirements in nine specific planning areas (See “Conditions to be Satisfied by June 15, 2015”). If the conditions are not met, Commission members say, “we anticipate a resolution of revocation of First Place’s charter contract to be presented with a strong likelihood of the resolution passing.”

Commissioner Cindi Williams reinforced this sobering message in a statement issued June 11th. Noting the commission had voted to give First Place “one last chance” to meet the requirements, she added, “...the Commission will be forced to make a decision based on the evidence presented as to whether First Place is meeting, or has a viable plan to meet, its obligations under the charter it signed a year ago.” If a majority of commissioners determine the obligation has not been met, First Place will be closed.

On a positive note, Commissioner Williams said the Commission and First Place leaders “share the same mission: providing our state’s most at-risk student population with an excellent education.” She complimented the school’s volunteer board and new director, Dr. Linda Whitehead, noting she felt “humbled by their dedication to each of the families in their care,” and that, “First Place is a safe place where students and their families feel loved and secure.”

Still, the regulations administered by the Charter School Commission appear to be more stringent than those required of traditional public schools. For example, First Place administrators must provide weekly reports of student progress, weekly test scores in reading and math, along with student and teachers schedules. This represents a level of oversight not seen in other Seattle public schools.

If First Place closes, at-risk families face limited alternatives. Nearby traditional public schools, like Hawthorne Elementary and Madrona K-8, rate in the lowest five percent of all schools in the state, according to rankings provided by the State Board of Education. Other elementary schools in the area, like Bailey Gatzert Elementary and Lowell Elementary, rate as “Underperforming” or “Fair,” according to state rankings.

Families often face imperfect choices. For families at First Place, for all its start-up problems, the charter school may serve as protection against a worse alternative; that their children would become subject to Seattle’s mandatory school assignment policy.

A further advantage of First Place charter school is that parents and caregivers are closely involved in the school. Charter school students are not subject to automatic assignment. No child may attend unless parents have indicated a strong interest in being engaged. The opt-in quality of First Place is especially important for homeless and at-risk families, where the need for services and support, beyond education, is especially acute.

The prospect of closing the state’s first charter school also raises two raise important questions. First, is it fair to hold First Place to a stricter standard than traditional public schools?

Administrators of traditional school districts seem in no hurry to close their underperforming schools. In south Seattle, the District operates low-performing schools year after year, with no discussion of closure for failing to serve students. In fact, failing public schools in Seattle often receive more money, time and support, in (often unsuccessful) efforts to turn these schools around. State rankings indicate the Seattle School District operates some of the lowest-performing schools in the state.

According to union policy, underperforming teachers in traditional public schools must be allowed three years to show improvement, despite the impact three years of poor instruction has on students. One-in-three minority students in Seattle drop out, and District officials report a 30 percent achievement gap between minority and white students in traditional schools. Despite this, First Place may be closed before the end of its first academic year.

Second, would closing First Place show respect for parents?

As noted, parents and caregivers involved in First Place have chosen the school as the best learning environment for their children. While members of the Charter School Commission wrestle with whether to close the school, the parents have already decided First Place is the right place for their children, at least for now. Otherwise, they would remove their children and seek assignment to one of Seattle’s traditional public schools.

As Commission members review whether First Place has met requirements in nine specific areas, First Place teachers and administrators have already met a tougher standard – the one demanded by parents.

While Seattle’s First Place School is not perfect, it currently serves some of the hardest-to-reach kids in the city. For these struggling children and their families, losing access to First Place may not mean being assigned to a low-performing public school – it could mean not being in school at all.

This report is part of Washington Policy Center’s Charter School Follow-up Project.