Last week Seattle Public Schools Superintendent Brent Jones (annual salary $335,000) announced plans to close 20 public elementary schools, representing one in four of the District’s 80 elementary schools. Without irony, he calls the plan “Well-Resourced Schools.” (Though I don’t see how a closed school is well-resourced.)

The shut-downs would force about 6,000 of the city’s youngest students out of their neighborhood schools to be consolidated into a larger and more crowded public school. Superintendent Jones says the closures are needed to free up funding within the $1.17 billion budget for the union contract he signed in 2022. Meanwhile, the budgets for non-teaching staff (about half of the District’s employees) and central administration remain untouched. For example, the budget line items for “District Leadership” and “Budget Planning” remain fully funded at $24 million and $17 million, respectively.

Many parents are naturally upset about the announced intention to close their children’s local public school. School board members say they plan to listen to public testimony at their next meeting. Apprehensive parents are likely to get about one minute each to present their concerns. Regardless of what school board members hear, however, we all know the likely outcome – they will close 20 elementary schools.

A popular state law, however, provides a way to keep schools open. In 2012, voters passed, and a large bipartisan majority in legislature confirmed, one of the best charter school laws in the country.

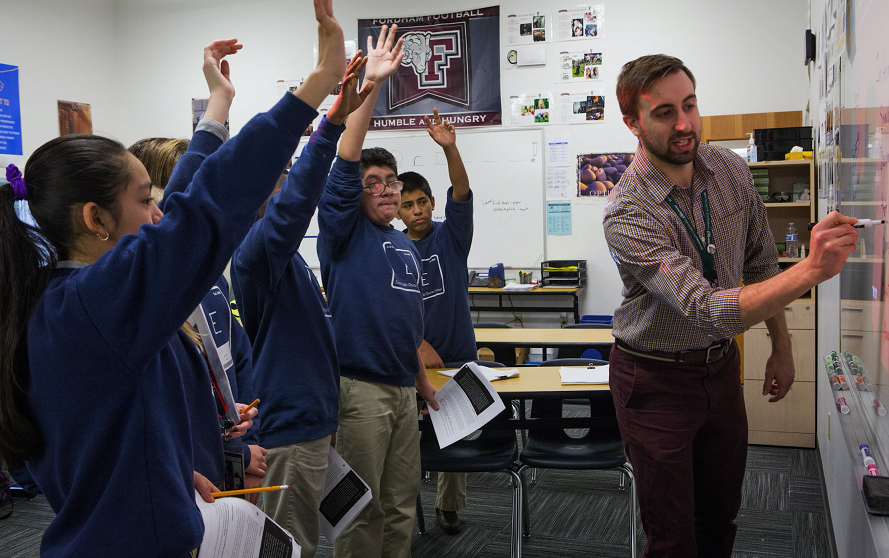

The State Charter School Commission based in Olympia reviews proposals from local communities to open a charter public school. Each school has a volunteer board, and receives per-student funding from the state and federal governments.

For example, if concerned parents at, say, Decatur Elementary, which is slated for closure, submitted a proposal to open Decatur Charter School, with access to the school’s current $2.4 million budget, the District could technically “close” the school, but it would continue to operate independently, possibly with the same principal, teachers and staff.

Recently Governor Inslee closed all public schools in Seattle, and across the state, for eighteen months. That painful experience showed many families that they can’t depend on “the system” to educate their children. The charter school law allows a public school to be run locally and independently, with less reliance on mysterious twists of bureaucratic rule or the intricate windings of District politics.

Instead of delving into a frustrating fight against the District, the solution for some Seattle communities may lie in tapping the state’s charter school law to keep their school open.