If the goal of the Portland Clean Energy Fund is truly to create a “climate-friendly Portland,” the first round of approved grants failed badly. This caught my attention, because it is similar to the failures we have seen in Washington, King County, and Seattle. It is also indicative of a trend where funding for environmental goals is siphoned off for other political agendas.

Adopted by city voters in 2018, the ballot asked voters to approve a tax that would “fund clean renewable energy (defined) projects, [and] job training.” A little more than three years later, the program is yielding very few clean energy projects or environmental benefits.

Instead, much of the Fund is going to “planning” for potential future projects and community organizations, rather than funding renewable energy projects. It is another example of how government programs sold on addressing climate change are being raided for other social and political priorities, doing little to address environmental problems. Just as we’ve seen in Washington State, science and effectiveness-based metrics are routinely being undermined by vague social motivations.

Despite the name of the program, it is doing little to actually provide “clean energy.” As one news organization reported, the first round of grants worth $8.6 million is projected to offset 11,500 metric tons (MT) of greenhouse gas emissions – costing about $750 to reduce each MT. That is astronomically wasteful. The typical price for reducing CO2 ranges from $10 to $30 per MT. Spending 75 times as much as that means the people of Portland are getting almost no climate benefit for their taxes.

A look at the projects that received funding reveals why the program is so ineffective.

A look at the projects that received funding reveals why the program is so ineffective.

The vast majority of the approved grants were for “planning.” The eight projects scored highest by city staff were all planning projects. These grants provided about $100,000 each, for example, to:

- “develop a clear roadmap,”

- “research and develop a program,”

- “development of a needs assessment,” and

- to conduct “workshops, trainings, and interviews.”

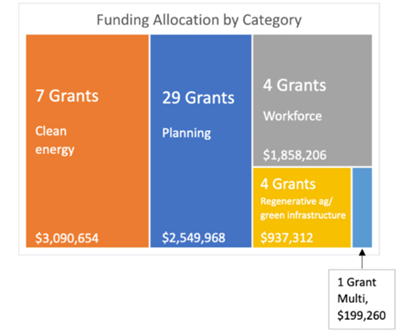

These planning grants accounted for 30%of the total spending from the Clean Energy Fund.

Projects that did actual work to install renewable energy – all of which were solar installations –or energy efficiency projects accounted for only 38% of expenditures. The return on investment for these projects varied widely, and many of the grant applications provided little information about potential benefits or the projections were extremely vague.

For example, one energy efficiency project that received about $165,000 says only that “The average annual cost saving is from 40 to 50% per household (the United States Department of Energy cites 50% savings).” It does not explain why they think this estimate is appropriate for the project they propose, nor how much money that will save for the people served by the program.

Even the projects that provide clear estimates of savings fall far short of providing environmental benefits equal to the cost of the grant.

The “Frontline Forward: Community-led clean energy transition” grant plans to install solar panels and improve the energy efficiency of low-income houses. The grant application is one of the few to provide detailed projections of energy and cost savings. For example, they estimate the solar panels will generate 806,276 kilowatt hours (kWh) over the lifetime of the project. This would replace electricity from Portland General Electric, which is generated using 42% natural gas and 33% coal. Each 2,000 kWh provided by solar panels avoids about one MT of CO2.

The applicants estimate that energy savings from retrofits would reduce heating oil use by 55,800 gallons and natural gas by 155,760 therms (each therm is 100,000 BTUs of energy) over 20 years. Over the course of two decades, they estimate this will save residents $321,000.

This all sounds good, but the grant provided by the city to achieve all of this amounts to $889,884. Even if we include the value of the CO2 reduction, this costs much more than the combined benefits.

We will assume the $321,000 is accurate. It does not appear to be discounted, meaning they treat $100 today the same as $100 in 2040, which is not correct. You wouldn’t want to spend $100 today to save that same amount two decades from now.

We can add to that the value of the CO2, using two metrics. The first is the market rate of CO2, which is about $10 per metric ton. To be very conservative, however, I use the current California price in their cap-and-trade system of $29.15. The other metric is the “Social Cost of Carbon,” (SCC) which is a rough estimate of how much damage each MT of CO2 does to the planet and economy. The current estimated price used by the Biden Administration is $51/MT, increasing to $73/MT twenty years from now.

Using either of these values, this grant – which is probably the best of the seven clean energy grants – still falls short.

Using a 3% discount rate and an increasing SCC, the value of the CO2 avoided over 20 years is $565,214. Added to the projected $321,000 in cost savings, the total amounts to $754,599, or $135,285 less than the value of the grant. Using the market rate, the value is even worse. The market value of that CO2 is just $277,685, for a total of $598,685. The City of Portland is spending $291,199 more than the value of reduced energy to low-income families and CO2 reduction.

The likely reaction to these numbers will be to argue that there are other intangible benefits, such as jobs, worker training, etc. Those benefits could, however, be provided with programs that yield better environmental results. At the very least those goals are undermining the stated purpose of creating clean energy and reducing the risk from climate change.

Since the program is called the “Clean Energy Fund,” one would expect it to yield a large amount of clean energy. However, most of the programs yield no clean energy and are justified only because they provide grants to “priority population(s) (i.e., people of color, women, people with disabilities, people with low income, or people who are chronically underemployed).” Program supporters can argue that is a worthy goal, but the goal of reducing CO2 emissions using “clean energy” is clearly secondary. Even projects designed to deliver clean energy offer only a small amount of CO2 reductions compared to the cost. Most of the funding yields no CO2 reduction.

The Portland Clean Energy Fund is another example of government spending where the effectiveness of providing environmental benefits is undermined by political preferences. Skepticism among the public about the seriousness of climate change, and the sincerity of politicians, will continue to grow as long as programs that purport to help the environment are revealed to be excuses to fund other political priorities.