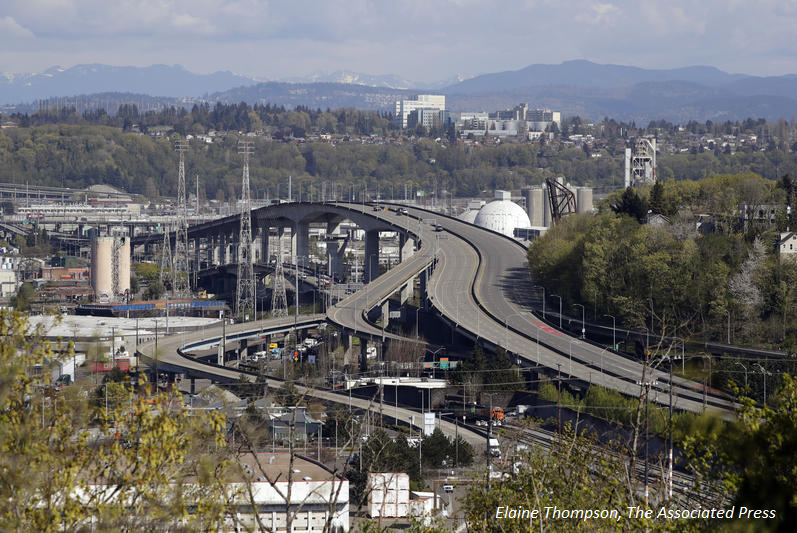

The West Seattle Bridge was first opened to traffic in 1984, replacing a twin drawbridge (or bascule bridge) that had been struck in 1978 by the freighter Chavez. Its replacement – a segmental bridge supported by concrete girders - was supposed to last 75 years. It has, instead, lasted 35. This is unacceptable.

As I keep reading reports and articles, the questions that will not leave my mind are, “How could a bridge deteriorate so badly at only half of its intended lifespan?” and “Who didn’t do their job?”

Reports indicate that unless there are interim repairs to cracks and restrained bearings, and the 150-foot bridge is supported as soon as possible, there is a risk of failure, partial collapse, and potentially a full collapse of the entire main span. The Seattle Times reports what failure might look like here.

Seattle officials first noticed cracks in 2013, choosing to monitor rather than repair them, as advised by consultants who evaluated the damage. The cracks grew through 2018 and 2019, at which point SDOT started filling them with epoxy to protect steel tendons that could get exposed to moisture and corrosion. They also increased exterior inspections, though Kevin Schofield at SCC Insight reports that between 2014 and 2016, inspection reports were “largely identical,” suggesting that some were “not carefully written” to accurately “represent the state of the bridge at the time.”

Earlier this year, the cracks grew a remarkable two feet in just two weeks, and SDOT closed the bridge to traffic. This was a good decision and likely saved many lives.

Though cracks were kept under observation, it seems SDOT wasn’t seriously concerned until 2019 when they started getting longer.

Increased regional growth and traffic congestion over the years has added wear and tear to the bridge. Washington’s climate and the bridge being built over an earthquake fault are also stressors, but these are two factors that some feel should have been accounted for by competent engineers. I’m inclined to agree. Bridge designers and engineers doing the best they could in the 1980’s with the information they had at the time does not absolve them of accountability. They are responsible to get the information they need to make good decisions in building a bridge that lasts the 75 years they say it will.

Two consultants suggested the 2001 Nisqually earthquake “which shook the bridge 3 inches according to SDOT inspection records – could have weakened it years earlier.” One consultant noted that “cracks in the bottom of the box girder were not a structural concern…but he also couldn’t determine whether the shear cracks in the walls – at the time showing slow growth over the years – were a cause for concern about the structural integrity of the bridge and its ability to carry a load.” Concrete girders are key to how the West Seattle Bridge is supported, and shear cracks “can lengthen quickly and lead to rapid failure.”

Seattle DOT has said that it has “been paying special attention to the cracks for years, and only in recent months did the damage begin to raise questions about the bridge’s stability.” There are some cracks that now “stretch nearly the entire 10 feet from floor to ceiling inside a girder.” This is pretty unsettling. SDOT should be audited to determine if more could have been done to reinforce any of the cracks and prevent the situation we’re in now. When it comes to infrastructure, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

As one commentator pointed out on the SCC Insight blog, “If a localized failure causes the entire structure to be un-repairable, then someone failed to do their job. We should determine who that was. Otherwise, we are setting ourselves up for a repeat performance.”

Knowing who caused the problem, and holding them accountable, is critical to the process of repairing or replacing this bridge. Engineers who failed to accommodate for potential problems and challenges in designing the bridge should be held accountable. Seattle DOT officials who took notes of damage and submitted reports when they probably needed to be making significant, needed repairs should be held accountable as well.

Without public accountability and personal consequences for failure, there are no incentives and certainly no reason to trust that SDOT officials will produce a cost-effective, long-lasting solution. If officials are truly interested in putting people first, they should recognize that the true value of accountability is to ensure the people they claim to serve do not continue to suffer and pay the overwhelming cost for agency failures.