Download a PDF of this Policy Brief as it appeared at Johnlocke.org in February 2016.

Summary and Highlights

North Carolina taxpayers are the winners when public schools operate efficiently and when every public dollar is put to its best use and evaluated carefully. Officials and administrators who pursue these goals should be applauded for their commitment. But good intentions do not ensure beneficial outcomes.

Such is the story with “green” school buildings in North Carolina. This report analyzes “green” facilities in four school districts: Wake, Durham, and Buncombe counties, along with the Iredell-Statesville public schools. Research focused on schools receiving certification from the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environment Design, or LEED, system.

This report’s author concludes “green” school buildings in North Carolina fall far short of their promises to protect the environment through lower energy costs and increased efficiency.

- None of the “green” schools are best-performing in energy use when compared to similar schools in the same district

- In every school district, at least one of the “green” schools performs below average compared to similar schools in the same district

- In many cases “green” schools require changes that end up increasing cost and reducing energy efficiency

- Buncombe County: Instead of using 30 percent less energy, the county’s two green schools used 7 percent more energy than nongreen schools

- Iredell-Statesville: Third Creek Elementary is billed as the first LEED “Gold”- certified school building in the nation but spends about $7,775 more per year on energy than the district’s average elementary school

- Durham County: Among 28 comparable schools, the two green schools rank No. 10 and No. 15 in energy efficiency, with both schools performing significantly worse than a much older district school that spends about 34 percent to 37 percent less on energy

- Wake County: The district’s one “green” elementary school uses more natural gas per square foot than comparable elementary schools in the district

- Policymakers seeking efficiencies in school construction should analyze the lackluster results of their sister districts and invest public dollars only in methods and technology that produce savings and benefits

Introduction

Charles T. Koontz and Joe. P. Eblen Intermediate Schools in the Buncombe County School District were designed as models of energy efficiency.

Built in 2011 and 2012, these schools received certification from the U.S. Green Building Council’s (USGBC) Leadership in Energy and Environment Design (LEED) system. Both are LEED Silver certified and were designed to use “30-35 percent less energy than a typical school.”

Now that they are a few years old, do they meet that standard? The answer is “no.”

Utility data from the 2014-15 school year show that, when compared to other middle schools in Buncombe County, the two schools rank below average for energy efficiency, using more energy per square foot than most of the other schools. Both schools spent 77 cents per square foot for energy through May of 2015, compared to the average of 72 cents per square foot for the other eight middle schools in the district. Instead of using 30 percent less energy, these green schools used seven percent more energy than non-green schools. These schools are not unique. Across North Carolina and the United States, so-called “green” buildings often use more energy than their non-green counterparts in the same school districts. For example:

- In Spokane, Wash., none of the new green elementary schools are as energy efficient as the traditionally built Browne Elementary School. One of the allegedly green schools uses 30 percent more energy than Browne.

- In Santa Fe, NM, the facilities director reports the district will not build another green-certified building anytime soon after the first such building, Amy Biehl Community School, consistently incurred some of the highest energy costs in the district.

- USA Today found in 2012 that green schools perform poorly in Houston as well. The newspaper reported, “Thompson Elementary ranked 205th out of 239 Houston schools in a report last year for the district that showed each school’s energy cost per student. [Green school] Walnut Bend Elementary ranked 155th.”

The situation is similar in North Carolina, where a number of schools intended to save energy actually use more energy per square foot than other schools.

Of course not every green school performs poorly. Some green schools are more efficient than their counterparts in the same district. Even when that is the case, however, green schools are usually more expensive to build and operate than traditionally built schools, raising the question of whether they save money for the local school district.

In many cases green schools require changes that end up increasing cost and reducing energy efficiency. One facility director in North Carolina indicated that meeting LEED standards for one school would have required including a larger air conditioning unit to increase air circulation in the school. That larger unit would not only have cost more; it would have used more energy. Such counterintuitive requirements are one reason LEED green schools do not live up to their promises.

In this report we examine green schools in four North Carolina school districts – Buncombe County, IredellStatesville, Durham, and Wake County – to compare the energy performance of those schools to others in the same district. Schools provide a good opportunity to assess green building standards in general because schools are about the same size; have the same building elements; are located in the same climate; and there are a number of similar buildings nearby for comparison.

Do Green Schools Live up to Their Promises?

Advocates claim that green schools produce many environmental benefits. The USGBC defines a green school as “a school building or facility that creates a healthy environment that is conducive to learning while saving energy, resources and money.” Many of these points involve subjective judgments that are difficult to measure. Efforts to link the supposed health benefits from green buildings and the learning progress of students are vague and subject to many other influences.

Energy use and energy costs, however, are useful and objective metrics that can be easily measured and compared. Since a reduction in energy use is at the center of what it means for a building to be green, it is the most useful way to compare the actual environmental results of these schools to traditionally built schools. Additionally, we try to compare schools built recently. The question is not whether new green schools are superior to old, traditionally built schools. The important question is whether spending more for a new, green school will yield cost and energy savings compared to a new, traditionally built school. Stated another way: Does the energy use of green buildings justify their significantly higher construction and operating cost?

Using this metric, the green schools in North Carolina that we studied fare poorly. Every school district that we studied in the state has at least one green school that uses more energy per square foot than a traditionally built school located in the same district.

At a time when resources for education and for protecting the environment are scarce, state legislators and policymakers should look closely at green schools and question whether policies that promote or require those costly standards actually yield the promised benefits.

What are Green Buildings?

Before examining the performance of green schools in North Carolina, it is important to know what the term means. Although definitions vary, the most common standard for green schools is the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) system created and promoted by the USGBC.

To meet the LEED standard, building designers must achieve points in a number of categories. The LEED checklist for schools includes categories for:

- Sustainable Sites

- Water Efficiency

- Energy and Atmosphere

- Materials and Resources

- Indoor Environmental Quality

- Innovation and Design Process

- Regional Priority Credits

Points are awarded in each category and if a school design receives 40 out of a possible 110 points, it is certified as green. At 50 points a building achieves LEED Silver status; at 60, LEED Gold; and at 80 or above, Platinum, the highest rating. Our study covers a variety of certification levels, including some at the lowest end of the scale, like Silver-rated W.G. Pearson Elementary School in Durham, as well as some meeting the LEED Gold standard, like Third Creek Elementary in the Iredell-Statesville School District.

Some rating categories are specifically designed to save energy, such as points for energy savings in a computer simulation of the building. Others are unrelated to energy, like the four points awarded for “Public Transportation Access.”

Advocates of LEED argue this system of flexibility allows schools to meet the standard at a relatively low cost. As districts move up the ladder of certification toward Platinum, the flexibility is reduced and the cost can increase significantly. As we shall see, even at the low end of the green building spectrum, the additional design, construction and operating costs more than outweigh the energy savings achieved by the buildings.

Data Transparency

One thing is worth noting. We have examined energy efficiency for schools in several states and we have never had as much difficulty receiving public data as we did in North Carolina. At one end of the transparency spectrum were officials at Buncombe County Schools, who provided the data within one week of our request – one of the best responses we have seen.

At the other end of the spectrum, however, were officials at Wake County and Iredell-Statesville. Requests were made at the end of the 2014-15 school year, both so we could get a complete school year, and so other school-related demands would be reduced. Despite that courtesy, Wake County officials provided the data three months later and the electricity data appeared incomplete. Meanwhile, Iredell-Statesville officials provided printed copies of the electricity, natural gas and sewer bills in a large cardboard box.

Having worked at a state agency that had to respond to many public disclosure requests, we certainly understand the time and effort it takes to compile requested information. We also understand that school districts are not staffed to respond to such requests on a regular basis. The wide gap in response time between districts within the state, however, indicates the problem with compliance had less to do with staffing or time than with the simple failure of school officials to prioritize transparency.

It was the most difficult time we have had in receiving data that should be readily available from public institutions.

Buncombe County School District

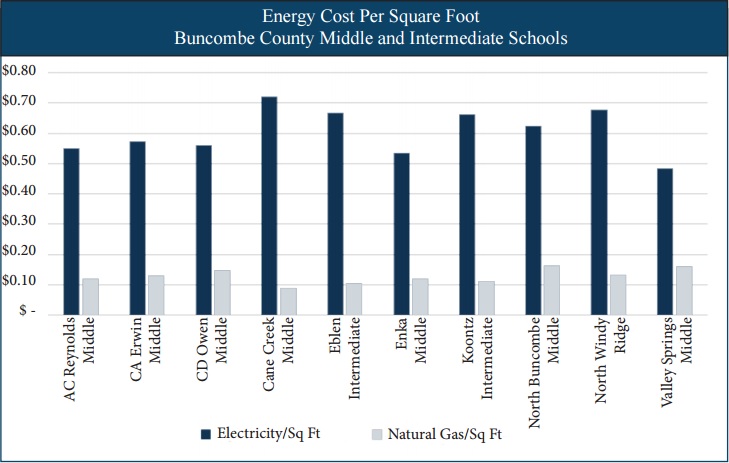

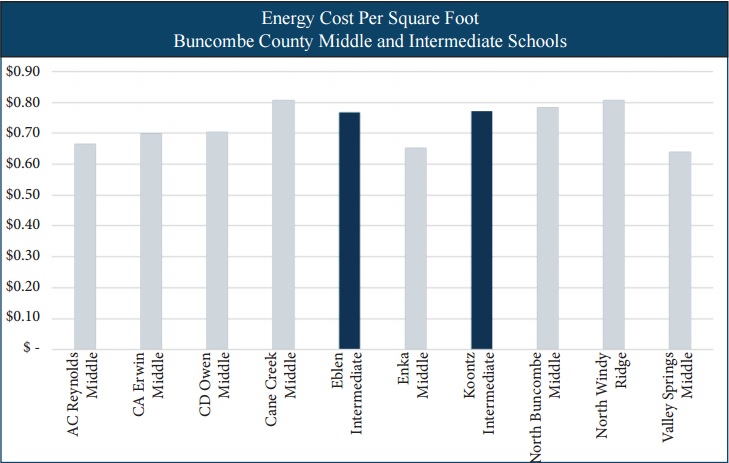

Buncombe County school district has two green schools. Both are Intermediate schools that serve children in grades 5 and 6. In total the district has 10 middle and intermediate schools. To ensure our comparisons are accurate, we compared the green intermediate schools to the performance of other schools of similar size and type in the same district. Here are our findings.

Joe P. Eblen Intermediate School

During the 2014-15 school year, green-designed Eblen Intermediate School used 6.2 kilowatt hours (kWh) per square foot and 13.7 cubic feet of natural gas per square foot. The school uses little natural gas, ranking second in the district for natural gas use per square foot, but is second-to-last in electricity use, ranking ninth out of ten middle/intermediate schools.

On a cost basis, Eblen spends 77 cents per square foot for energy, ranking it 6th out of the ten schools in the district. As noted above, Eblen spends seven percent more than the non-green middle schools in the district and 20 percent more than the most efficient middle school in the district, Valley Springs Middle School, built in 1989.

One reason older schools use less energy is that they have fewer power draws and can have poor air conditioning systems, making the buildings less comfortable. Clyde A. Erwin Middle School – built seven years earlier than Eblen in 2004 – uses nine percent less energy per square foot.

Far from using 30 percent less energy – as the designers claimed – Eblen uses more energy than most other equivalent schools. If Eblen were simply as efficient as the average of the other schools, energy costs would be $5,746 lower per year.

Looking at the best scenario, the difference between Eblen and the worst-performing school, North Windy Ridge, is also very small. Eblen only uses about five percent less energy than North Windy Ridge. Bringing North Windy Ridge up to the standards of Eblen would have saved the district only about $3,800 a year, or $76,000 over the typical 20-year lifespan of a school building. For a building that cost about $14 million, that represents a savings of one-half of one percent. Typically green schools cost at least two percent more to build, meaning the undiscounted loss would be $204,000 in the best circumstances.

However, since Eblen actually performs worse than the average building, the additional cost to meet the LEED standards will likely never be recovered.

Charles T. Koontz Intermediate School

Built at the same time, using the same green approach, the energy-use numbers for Koontz are almost identical to those of Eblen Intermediate School.

During the 2014-15 school year, Koontz Intermediate School used 5.8 kilowatt hours (kWh) per square foot and 14.8 cubic feet of natural gas per square foot. The school uses little natural gas, ranking third in the district for natural gas use per square foot, but ranks seventh out of ten middle and intermediate schools in electricity use. On a cost basis, Koontz performs slightly worse than Eblen, spending about 77 cents per square foot for energy use, making it the seventh-best school in the district for energy efficiency.

As in the case of Eblen, the additional cost to meet the LEED green building standards did not yield the promised energy savings. Ultimately the district spent more money to construct buildings that are less efficient.

Green school advocates offer a number of explanations for why buildings fail to deliver promised energy savings. We will discuss these reasons in detail below, but one is worth mentioning here. New buildings – green and traditional – often have more amenities, including air conditioning and more electrical outlets to accommodate computers and other equipment. Green school advocates, then, claim that new schools are more comfortable and more accommodating than traditional schools. For this reason, they might argue, comparing a school built many years ago to one built today is invalid.

There are a couple of problems with these justifications.

First, five of the other eight schools use less energy, so any justification may account for some, but not all, of the discrepancy. Second, labeling the schools as “green” implies they are more energy efficient and have a smaller environmental impact than other schools. Arguments that attempt to explain away additional impact on the environment by citing added amenities demonstrate that the adjective “green” is less important than other design goals, like building comfort. It is hard to continue to call these “green” buildings when the designer has sacrificed reducing environmental impact in favor of other, energy-using priorities.

Compared to the promised savings, neither of the green intermediate schools in the district perform as promised. Given these poor results, it is likely that spending additional school funds to meet the green standards would not be a beneficial public expense.

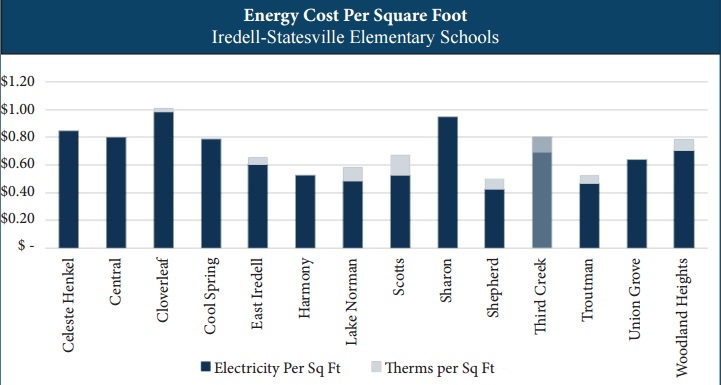

Iredell-Statesville School District

There is only one LEED-certified elementary school in the Iredell-Statesville school district, but it holds the distinction of being “the first elementary school in the nation to be certified as a LEED Gold building.” Built in 2002, it is older than many green schools around the country and provides a good opportunity to see whether green certification stands the test of time, especially since this school was built to such a high standard.

We compared Third Creek to other elementary schools in the district for the period of July 2014 to April 2015 because some schools did not provide data for May 2015. Additionally, we eliminated schools for which data were unavailable or incomplete. Ultimately, we compared 14 of the 17 schools and the data show a wide range of energy performance. The chart shows the electricity and natural gas use per square foot for each of the 17 schools we examined.

The schools range in size from 51,698 square feet to 108,960 square feet. Third Creek Elementary School is toward the upper end at 94,000 square feet. There does not, however, appear to be a relationship between the size of the school and per-foot energy use.

Third Creek Elementary

Of the 14 elementary schools, Third Creek Elementary ranks 11th in total energy cost per square foot, spending 80 cents per square foot over the course of the year. It spends about 12 percent more for energy than the average elementary school in the district, and about 60 percent more per year than the best-performing school, Shepherd Elementary.

Overall, Third Creek Elementary spends about $7,775 more per year on energy than it would if it were as efficient as the average elementary school in the district. Over the 20-year lifespan of the school, that would mean an additional $155,500 in energy costs.

Additionally, the school cost $8,749,600 to build in 2002. Applying the conservative two percent additional cost for green buildings – especially since it met a high standard – added about $171,560 to the total cost. If the school saved energy early in its life, it certainly is not doing so now, meaning the district probably did not recover the additional cost to meet the LEED Gold standard. Between additional construction costs and energy costs, Third Creek Elementary will cost the district an estimated $327,000 more in energy use.

The district does not have another LEED-certified building, so administrators may have recognized that the promised “green” benefits do not match the additional costs when building and remodeling schools in recent years. Given its age, the high level of certification it received and its performance, Third Creek Elementary is a warning to other school districts about the gap between the promise and reality of building “green” schools.

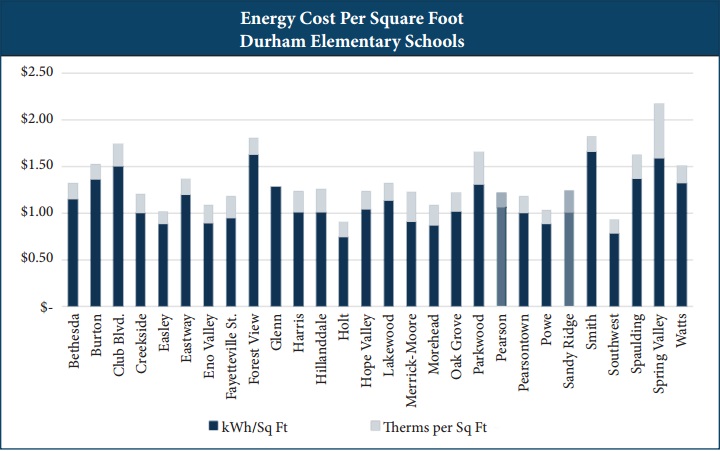

Durham School District

There are several LEED-certified schools in the Durham school district, including two buildings that meet the LEED Gold certification level. Two of the green schools are elementary schools, and with 30 elementary schools overall, they provide an excellent opportunity to compare the energy-saving performance of the LEED certified schools to traditionally built schools.

The two green schools are W.G. Pearson Elementary School, which received the lowest level of LEED certification, Silver, and Sandy Ridge Elementary School, which is certified at the LEED Gold level – the second highest level available.

Although there are 30 schools in the district, we have chosen 28 for comparison, all of which purchase electricity from Duke Energy and natural gas from PSNC Energy. The other two schools – Little River and Mangum – purchase their electricity from other sources. As a result, their rates and other price variables may be different. If there were more diversity of utility suppliers among the schools, we would include them, but since these two schools are outliers, the best approach to obtaining an accurate apples-to-apples comparison is to choose the 95 percent of elementary schools that use the same utility supplier.

Additionally, most of the schools have similar ratios of electricity and natural gas use. Only one school, Glenn Elementary, uses only electricity. Finally, the schools are, for the most part, similar in size.

Sandy Ridge Elementary School

The data from the most recent school year, 2014- 15, shows Sandy Ridge Elementary, which is LEED Gold certified, actually ranks 15th out of 28 schools, or slightly below average. It uses about 37 percent more energy than the best-performing school, Holt Elementary, which was last remodeled in 1992. Comparing it to more recently-built schools, Sandy Ridge uses about 3.5 percent more than Creekside School, built in 2004 and remodeled in 2010.

The construction cost for Sandy Ridge School, including for the landscaping and parking lot, is reported at $15,357,880. Using the two percent cost increase average, meeting LEED standards would add about $301,133. This is probably low, because two percent is the average for LEED certified buildings and estimates show that meeting LEED Gold is much more expensive to achieve.

Additionally, if Sandy Ridge were as energy efficient as Creekside, it would save the district an additional $4,282 per year. Over the 20-year lifespan of the building, it will spend an estimated $85,650 more than if it were as efficient as Creekside.

Ultimately Durham Public Schools will spend nearly $400,000 more for a building that is supposed to be more energy efficient, but actually performs worse than the average school.

W.G. Pearson Elementary School

Pearson Elementary School performs better than Sandy Ridge School in energy use, despite actually achieving a lower level of LEED certification. Out of the 28 elementary schools we examine here, Pearson ranks tenth overall, just behind Creekside School, which ranks ninth.

Both schools perform significantly worse than Holt Elementary which was last remodeled in 1992 and spends about 34 percent less on energy than Pearson and 37 percent less than Sandy Ridge. Southwest School is next-best, and was constructed in 1991. The fact that the two most efficient schools were built within a year of each other indicates the builders at the time were focused on efficiency.

It is also likely they use less energy because they were designed with fewer electricity draws than newer schools. This is likely in the case of Pearson Elementary. Pearson ranks fifth among the 28 elementary schools we looked at for natural gas use, but sixteenth in use of electricity per square foot. It seems likely that the increased electricity use is due to the inclusion of more electrical equipment or more outlets for such equipment.

Interestingly, results for Sandy Ridge show the opposite. It ranks 11th overall in electricity use per square foot, but 21st in natural gas use. There is no obvious reason – other than the fact that the LEED Gold certification simply is not delivering on its promises – that the school would perform so poorly.

Ultimately Durham Public Schools’ green elementary schools do not live up to their alleged distinction. Compared to other elementary schools in the district, their level of energy efficiency is about average. Indeed they perform slightly worse than Creekside Elementary, which was built and remodeled in recent years but did not seek or receive LEED “green” certification.

In such circumstances it is our experience that some school districts justify the additional cost of building “green” by pointing to other amenities. That may or may not be true, but at the center of “green” claims about LEED buildings is that they are more environmentally friendly by saving energy, that the higher cost is worth it because they are helping to save the planet. That is not the case with Durham’s two green elementary schools.

Wake County School District

The largest school district we examined, the Wake County Public School System, has one LEED-certified “green” school, Alston Ridge Elementary School, out of nearly 100 elementary schools in the district. Alston Ridge was certified LEED in 2013. It received the lowest level of certification, Silver, and it received very few of its points in the Energy and Atmosphere category. For this reason we would not expect to see the building perform significantly better in energy use than other schools, since certification was achieved by scoring points in other categories like “Indoor Environmental Quality” and “Water Efficiency.”

Although there are many other elementary schools in the district, comparing the performance of Alston Ridge to other schools is difficult due to inconsistent data. For example, half of the schools provided no data related to electricity costs. Additionally, while virtually all schools reported natural gas data, the cost per square foot varies significantly, with some schools paying six times as much as others. One reason for these anomalies could be that meters are shared by schools or different buildings and are, therefore, allocated to other schools.

To address this, we focused only on natural gas data. The data fall within a general range and with the large number of schools, they help minimize the impact of outliers. About 90 percent of the schools have natural gas bills that fall between five and 15 cents per square foot. This provides a fairly consistent basis for comparison.

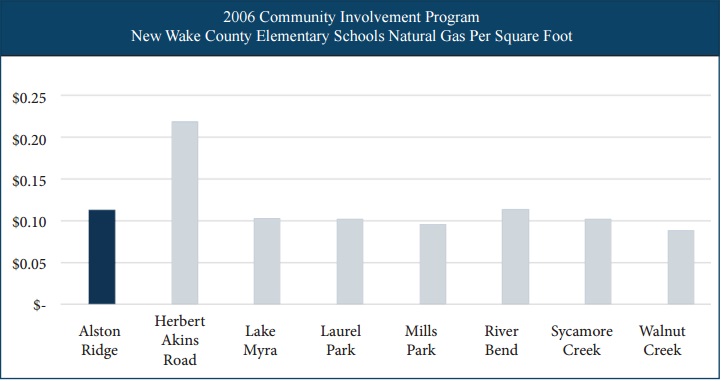

Additionally, we also focused on the other new elementary schools built as part of the district’s 2006 Community Involvement Program to build and refurbish district schools. There are eight new elementary schools built during this project for which we have data.

Alston Ridge Elementary School

The only LEED-certified school in the district, Alston Ridge opened in 2010 and was certified in 2013. At nearly 105,000 square feet, it is about 15 percent larger than average, but within the typical range for elementary schools.

For the most recent school year, Alston Ridge spent 11 cents per square foot for natural gas, exactly the average amount for all the elementary schools in the district. Additionally, compared to new elementary schools built as part of the district’s 2006 Communty Involvement Program (CIP 2006) building program, it uses slightly more natural gas per square foot. Herbert Akins Road Elementary is an outlier at 22 cents per square foot, but all other elementary schools built as part of the CIP 2006 program have costs ranging from 11 cents per square foot down to nine cents per square foot, for Walnut Creek Elementary School. Alston Ridge spends about $1,300 more per year than the average of the other new elementary schools built under the CIP 2006 program.

As we mentioned, electricity data are inconsistent for these schools. For example, although Alston Ridge reported more than $59,000 spent on electricity and lighting in 2014-15, none of the other schools reported more than $15,000 in those areas. Focusing only on natural gas provides a level playing field for comparison of all these new schools.

Additionally the building cost $24,469,718 for construction, putting the LEED certification cost estimate at about $479,800. The district achieved the lowest level of LEED certification and appears to have chosen low-cost methods to meet the standard. As a result, the additional cost may be closer to the two percent of budget or even lower. Whatever the level, the school is using more natural gas per square foot than comparable elementary schools in the district.

As we noted above, it is not surprising that we do not see significant – or indeed any – energy savings from Alston Ridge, because of the focus on earning LEED points outside the energy efficiency area. That conclusion is borne out by the data.

North Carolina Green Schools – The Results

Of the four North Carolina school districts examined by this study, none have green schools that help “protect the environment” as their promoters had promised. Further, none of the schools will come close to energy savings that recover their higher initial construction costs, and most schools are less efficient than their nongreen counterparts located in the same districts.

Results are fairly consistent across the districts. None of the green schools are best-performing in energy use, and in every school district at least one of the green schools performs below average, compared to similar schools in the same district. Ironically the two LEED Gold schools, LEED’s second-highest ranking, in this study perform worse than the average school in their districts. Given the difficulty of meeting that green standard, we would expect to see above average levels of energy efficiency, since they cost so much more to build.

The consistent failure of green buildings to produce promised energy savings is not unusual, as we noted above. The performance of North Carolina’s green schools, however, is a further indication that legislators and school officials should think twice before requiring schools to spend additional taxpayer and school dollars to earn LEED certification. The experience of schools across the country demonstrates that district facilities directors are often adept at finding cost-effective ways to reduce energy use, based on the particular buildings they manage. Requiring them to meet a formulaic, one-sizefits-all approach, however, often leads them in the wrong direction, increasing costs without returning savings.

Our discussions with facilities directors in North Carolina, and the fact that some districts have not sought LEED certification for new schools, indicates they have been unsatisfied with the results of green schools.

The failure of green buildings to produce energy savings as promised is also an environmental failure. Many advocates who promote LEED or similar rating systems point to the supposed carbon dioxide emission reductions achieved by green schools. The failure to save energy, or even slow the increase in energy use, wastes resources on efforts that do nothing for climate change or the environment. Instead misguided green building rules divert scarce funding from efforts that could have a positive environmental impact, or which could be used to fulfill other public needs.

Ultimately – for taxpayers, students and the environment – the real-world data shows that North Carolina’s green schools fall well short of their energy saving promises.