EIS or WAG? Ecology Bases Policy on Guesses, Not Reality

On April 28, officials at the state Department of Ecology (Ecology) released their environmental assessment of the proposed export terminal in Longview. A key part of their report is a prediction about the environmental impact caused by coal that might be exported through the port. This is the first time environmental officials have tried to analyze not only the effects of a construction project, but of the worldwide economic and environmental effects of future products that might pass through the project once its completed.

The analysis is a perfect example of the flimsiness of setting environmental policy based on data that are essentially meaningless. The Department of Ecology report contains a remarkable contrast between the stern tone the authors use to discuss the potential impacts of climate change and the extremely vague nature of the projections they make about carbon emissions from this specific project.

Despite Ecology Director Maia Bellon's claim the analysis is "state of the art," there are some clear indicators the analysis is spurious.

First, Washington is heavily dependent on exports of all kinds, from food to aluminum to Boeing aircraft. Department of Ecology officials, however, do not assess the impact of expanding those exports. Doing so would likely show large environmental impacts worldwide. The reason they ignore these impacts for other projects but included them here is about politics, not the environment.

Second, the huge gap between the upper and lower estimates of potential impact, demonstrates how useless the report is for making accurate policy. The authors themselves admit, “Due to uncertainty over future coal consumption trends, the coal market assessment constructed in the Upper and Lower Bound scenarios in a way that they provide illustrative results to provide a broad range of outcomes.”

Second, the huge gap between the upper and lower estimates of potential impact, demonstrates how useless the report is for making accurate policy. The authors themselves admit, “Due to uncertainty over future coal consumption trends, the coal market assessment constructed in the Upper and Lower Bound scenarios in a way that they provide illustrative results to provide a broad range of outcomes.”

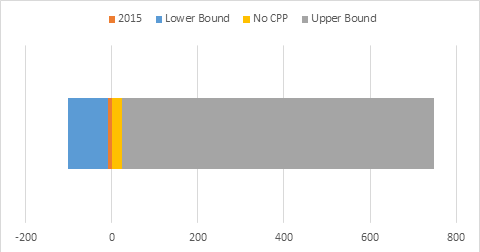

The authors consider four scenarios, including rules as they existed in 2015, without the Clean Power Plan and upper and lower bounds. The chart demonstrates how vast their uncertainty is, with some of their scenarios showing an actual reduction in emissions while their upper bound is 31 times as large as the impact the authors expect if the Clean Power Plan is removed by the Trump Administration.

This uncertainty is a result of the large number of factors that will change as a result of the potentially increased supply of coal and factors entirely independent of that supply. Here are just a few.

- Public policy – Ecology officials themselves notes US energy policy could change the estimate of emissions from a reduction of the equivalent of nearly 8.5 million metric tons of CO2 (MMTCO2e) to an increase of 53 MMTCO2e. They attempt to predict US public policy through 2038. Two years ago nobody expected Donald Trump to be president.

- A potential increase of 0.5% in supply – In 2015, total worldwide coal production was 7,708 million metric tons. The planned terminal will export about 44 million metric tons annually, or 0.5% of world production. Ecology believes it can accurately predict how this small amount will impact worldwide energy markets.

- Adjusting production – Those 44 million tons won’t all be additive. Other energy producers may reduce production of coal, or natural gas, or wind or other energy sources, in response, offsetting the increase. Ecology claims it knows how worldwide production would adjust to an increase of less than one-half of one percent in supply over twenty years.

- Adjusting demand – Worldwide demand may change due that increase, but a myriad of other factors come into play as well. In 2005, the International Energy Agency predicted total coal demand in 2015 would be 5,746 million metric tons. By 2015 actual consumption was just under 8,000 million metric tons. IEA officials were off by nearly 30 percent in just one decade. Yet Ecology officials believe they can predict what will happen over twice that time period within a reasonable margin.

- Global economic factors – Ecology officials use economic models to understand how all these factors, and more, impact total worldwide consumption. The state general fund revenue estimate, focusing only on Washington state and limiting its timeline to three months, was off by 2.6 percent between December 2016 and March 2017. Three months. If state projections are off by five percent a year, the error range over 20 years is 300 percent. Despite that, Ecology officials think they can accurately predict the worldwide economy twenty years from now.

- Technology – New breakthroughs will change the relative cost and demand of coal and other competing energy sources. Ten years ago, US natural gas production was the same as it was in 1973. During the past 10 years, however, production hit record highs, increasing about 40 percent in that short period. New technology – in this case hydraulic fracking – changed the energy landscape. Ecology officials believe they can accurately predict the course of technological breakthroughs over the next twenty years.

For the EIS to be a useful guide to environmental impact, the Department of Ecology has to understand how public policy, supply, demand, global economic trends and technology will all be impacted by a change of 0.5 percent of supply during the next twenty years within a reasonable margin of error.

Based on that spurious assumption, Department of Ecology leadership created permit restrictions to offset their assumed theoretical impact. Their admitted level of uncertainty is so large, however, the permit requirements they impose are arbitrary, because the requirements are based on a tenuous and indefensible estimate of the future.

We are constantly told of the need to base environmental decisions on science. The Department of Ecology’s analysis, however, is speculation masquerading as credible data. As a result, their permit requirements are arbitrary at best.

This isn’t just a problem with an EIS report as speculative as this one. The Department of Ecology does not go back and check the truth of their analyses to determine their accuracy. If policymakers are serious about making thoughtful, data-based decisions, we need to change the way officials try to estimate environmental impact.